It has never been easy to be an artisan in America. That was true when the United States was a new nation, and it is true today. In some ways, the challenges have not even changed that much. Yes, we seem to live our lives on permanent fast forward these days, with boundless opportunities for immediate gratification and distraction. Information and resources are more accessible than ever before. What used to be “mysteries of the trade” are now floating out there on YouTube. The most specialized tools and materials can be ordered for next-day delivery. Yet it still takes long years to achieve mastery in a craft. The difficulty of getting wood, leather, clay, fabric, stone or glass to do what you want remains the same. And the business side of earning a livelihood with your hands, day in, day out, is as demanding as ever.

These challenges, which all makers hold in common, can be great equalizers, giving craft the potential to cut across social divides and provide a powerful sense of continuity with the past. This possibility has never seemed more within our reach, for the United States is currently experiencing a craft renaissance, arguably the most momentous in our history. Not even the Arts and Crafts movement, which ended about a century ago, achieved the scale of today’s artisan economy—or anything like its diversity. This is big news, and it is good news. But it’s not necessarily simple.

To better understand this great resurgence of craft, I interviewed contemporary makers about their experiences of learning, setting up shop, developing a name for themselves, working with clientele and finally, passing skills on to others. Having recently completed a book on the history of American craft, I have been fascinated that many stories from the past find continuity with today. All across the country, craftspeople are prevailing over the challenges that invariably come their way, and longstanding traditions are being extended and transformed.

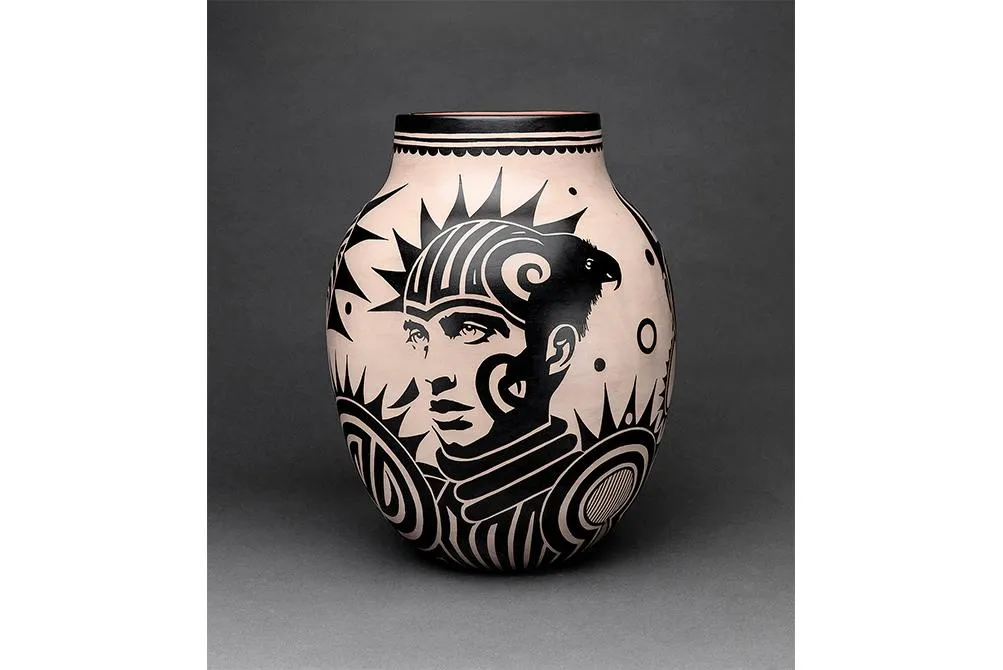

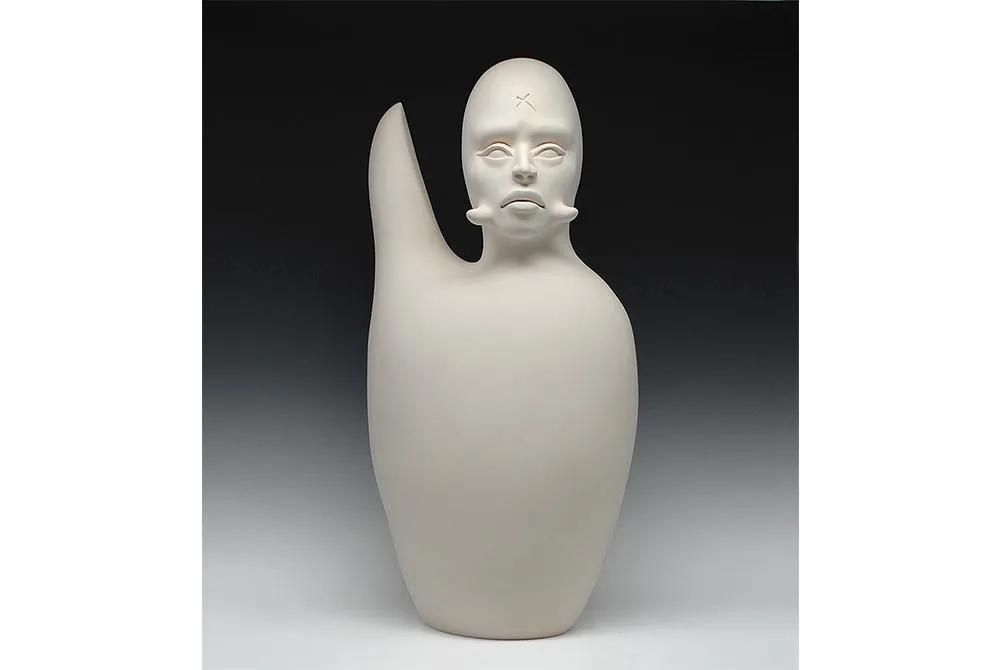

Take, for example, Virgil Ortiz. He began his career as a potter, drawing on the deep cultural well of Cochiti Pueblo, in New Mexico, where he was born and raised. While ceramics remains central for him, he works in other disciplines as well—film, fashion, jewelry and more. He picked up skills one after another, in what he describes as an organic process of development: “If I did not live close to an exhibition venue, I needed slides to present my work. So that led to photography. Then came magazine ads, so I taught myself graphic design. If I wanted a leather coat I had seen in a fashion magazine and could not possibly afford it, I taught myself how to sew. Each medium inspires another—it’s never-ending.”

Time Traveling

Having learned traditional clay pottery methods as a boy in the Cochitl Pueblo of New Mexico, Virgil Ortiz now works in costuming, fashion, film and jewelry as well. A longtime theme is the actual 1680 Pueblo revolt against Spanish colonizers—and his conception of those conflicting forces 500 years later, in 2180.

Ortiz’s work is equally far-reaching in its content. For many years he has been creating imagery based on the Pueblo Revolt, a successful uprising of indigenous people against the Spanish that occurred in 1680. Most people in the U.S. have never heard of this “first American revolution,” as Ortiz calls it, and he has set himself the task of elevating awareness of it. He tells the story in a complex and highly imaginative way, interweaving elements from a parallel science fiction narrative set in the year 2180 in an effort to reach younger audiences. His pots and figural sculptures are populated by his own invented characters, yet at the same time, keep the tradition of Cochiti clay alive: a sophisticated mixture of past, present and future.

Unlike most Americans today, Ortiz was surrounded by craft as a child. He was born into a family of potters on his mother’s side, and his father was a drummaker. “We were always surrounded by art, traditional ceremonies and dances,” he says. “I didn’t realize that art was being created daily in our household until I was about 11 years old. But I can definitely say that we had the best possible professors to teach us about traditional work.” When he was still young, Ortiz learned how to dig clay from the ground, process paint from plants, and fire pottery in an open pit, using cow manure, aspen and cedar for fuel. Having learned to use these methods and materials, he says, “it made every other medium seem a whole lot easier.”

It is tempting to imagine that, back in the day, all artisans had experiences like Ortiz’s and came easily to their trades. In fact, the picture is far more complicated. Certainly, there was a generally high level of material intelligence in the population. People understood how textiles were woven, furniture was built and metal was forged. Yet attaining a professional craft skill was not a straightforward proposition. The overall competency and self-sufficiency of Native Americans was regarded with considerable awe by white colonists, who generally lacked such capabilities. Guilds on the strict European model were nonexistent; in a young country defined by mobility, it was nearly impossible to impose consistent standards, or even keep artisans on the job. Young men were known to flee their indentures and apprenticeships before their terms were over, in order to set up their own shop and start earning—the most famous example being Benjamin Franklin, who went on to become a secular saint, the ultimate “self-made man.”

Yet this stereotype of the craftsperson as an upwardly mobile, native-born white man is misleading. The majority of craftspeople throughout American history were immigrants, women and ethnic minorities. All faced prejudice and economic hardship. Immigrant artisans often came with superior skills, because of their traditional training; but they tended to arouse suspicion and hostility among native-born workers, often to the point of physical violence. Women—half the population of skilled makers—were all but shut out of professional trades until the late 20th century. They had to practice their crafts informally at home, or while playing a supportive role in the family shop. Widows were an important exception: They became prominent in trades like printing and cabinetmaking, which were otherwise male-dominated. Betsy Ross probably did not design the Stars and Stripes, as legend has it, but she did run an upholstery business for more than 50 years following the death of her first husband—a great achievement in a society that little rewarded women’s enterprise.

The craftspeople who have contended with the greatest obstacles have been Native Americans and African Americans. The indigenous experience of displacement is a tragedy beyond reckoning; just one of its consequences was disruption to long-established ways of making. It has required a tremendous force of cultural will on the part of generations of Native people, people like Virgil Ortiz, to maintain and rebuild those bonds of culture.

The brutal realities of enslavement and racism make the stories of black craftsmanship especially fraught and painful, all the more so because, in spite of what they faced, African American artisans literally built this country. The extent of their contribution is being gradually revealed through archival research. Tiffany Momon, founder of the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive, has been a leading voice in this work; she and her colleagues comb through historical documents, looking for records of African American artisans and telling their stories. I asked her to explain what craft meant for black Americans in the 19th century. “Practicing a skilled trade provided enslaved craftspeople with some advantages,” she told me, “including the ability to, in some instances, earn wages and purchase themselves or their family members. The potential ability to buy oneself was undoubtedly a motivating factor for enslaved craftspeople to pursue and perfect their work. With the end of the Civil War, emancipation, and Reconstruction, you find that many formerly enslaved skilled craftspeople continued to practice their trades as freedpeople, enabling them to leave plantations for urban areas. They avoided the fate of many who ended up in exploitative sharecropping agreements with the former enslavers.”

Some of the most moving testimonies to black artisans’ lives are those they recorded themselves. The ceramics artist David Drake (often called “Dave the Potter”), who was born into slavery in Edgefield, South Carolina, inscribed his impressive large storage vessels with poetic verses. One heartbreaking couplet seems to speak to enforced separation from his own family members, yet concludes in a gesture of universal goodwill: “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all, and every nation.” The seamstress Elizabeth Keckley, who was born into slavery in Dinwiddie, Virginia, wrote in her autobiography, “I came upon the earth free in God-like thought, but fettered in action.” Yet she managed to become a much sought-after dressmaker in Washington, D.C. and a confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln in the Civil War White House. As a young man, Frederick Douglass was an enslaved ship’s caulker in Baltimore; he had terrible experiences during those years, but the future orator also drew deeply upon them in his later writings and spoke of artisan pride and opportunity. “Give him fair play and let him be,” Douglass wrote of the black artisan. “Throw open to him the doors of the schools, the factories, the workshops, and of all mechanical industries....Give him all the facilities for honest and successful livelihood, and in all honorable avocations receive him as a man among men.”

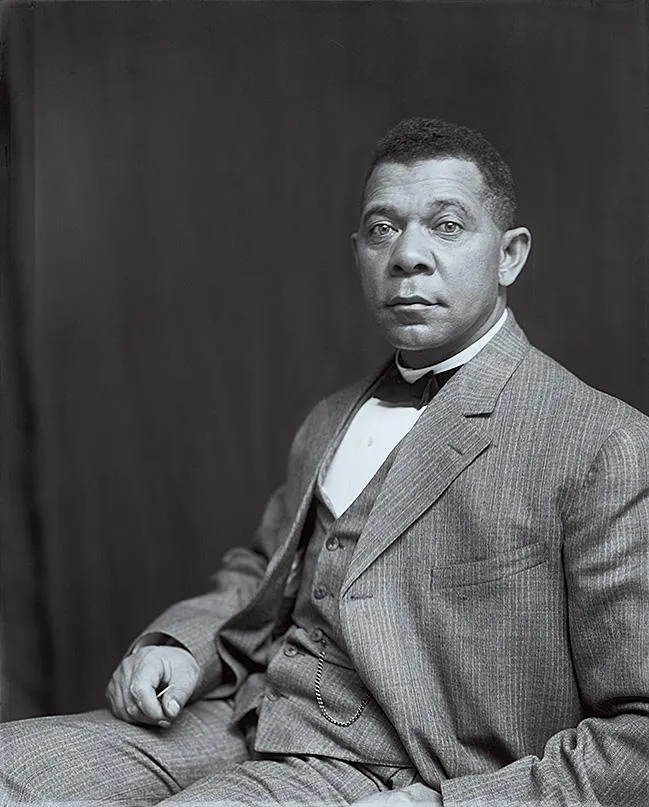

In the years following the Civil War, the educator Booker T. Washington led a nationwide effort to provide young African Americans with craft-based training, which he described as a means of uplift. The Tuskegee Institute, in Alabama, which he founded, and the racially integrated Berea College, in Kentucky, offered craft-based education for boys and girls, though it was strictly separated by gender—carpentry and blacksmithing versus sewing and cookery. But these efforts never adequately addressed the needs of black students. The courses were often poor in quality, separate and unequal, with behind-the-times equipment—problems exacerbated with the rise of Jim Crow, leading to the segregation of schools like Berea. By the time of the Great Depression—as Carter G. Woodson explained in his 1933 book The Mis-Education of the Negro—African American craftspeople still lacked equal access to training and employment.

Educators today continue the struggle against inequality. There is some cause for optimism. Federal funding for Career and Technical Education (CTE) is the rare policy for which there has been genuine bipartisan support over the past few years. And the introduction of digital tools, such as design software and 3-D printers, brings forward-facing legitimacy to such classes. Above all, though, are the efforts of individual educators.

Clayton Evans is a teacher at McClymonds High School in Oakland. He was born in 1993—“after the death of trades,” as he puts it—and had hardly any experience of making things by hand when he was growing up. After studying science and engineering in college, though, he came to see teaching as political work. Evans could be paraphrasing Douglass when he says he wants his students to “feed themselves and their families with what they are learning.”

He first went to McClymonds to teach physics, and immediately became curious about the old wood and metal shop. It was locked up, used by the janitorial staff to store unwanted items. But after getting inside the space, Evans realized it had “good bones”—the shop was wired with industrial voltage and had a stock of well-built old machines. He set to work, clearing out the junk, teaching himself to repair and operate the equipment. Before long he was instructing about 100 kids each year. Evans teaches old and new techniques: woodwork and metalwork, engineering fundamentals, digital design. He encourages students to “break out of a consumer mentality” and actually solve problems. When his school managed to acquire a set of 3-D printers, he didn’t teach the students how to make cute little objects out of extruded plastic, as is fairly common in maker spaces across the country. Instead, he showed them how to disassemble the machines, then rebuild and customize them.

Construction Zone

A physics and engineering teacher at McClymonds High School in Oakland, California, Clayton Evans is helping students build a better world in his innovative woodshop classes.

This path to self-reliance is connected to the one Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington had in mind. The difference, perhaps, is that Evans rejects the cliché of the “self-made” American. As he points out, it is literally impossible to pull yourself up by your own bootstraps (remember, he’s a physics teacher). The educational system must shift away from a generic, one-size-fits-all curriculum, he says, and instead provide tailored pathways to employment. And more than that: “I certainly want my students to have trade skills, and knowledge to hustle,” Evans says, “but their mind-sets are even more important to me. If we want freedom, we need to build lives beyond pathways to employment. Hopefully students’ time in my shop will help them build and sustain their communities in new, socially just economies.”

John Lavine, another CTE educator, who works at Westmoor High School in Daly City, California, runs a program teaching traditional skills like woodworking alongside new digital techniques such as laser engraving and robotics. His students are primarily of Latino, Arab and Filipino background, from immigrant, working-class families. They are sometimes able to get well-paid jobs right out of school, or start their own businesses. If they attend college, they are likely to be the first in their families to do so. Lavine aims for such positive outcomes for his students, but it is by no means a certainty for every one of them. All he can do, he says, “is inspire and train, and help them see a way forward.”

This same ethos animates craft at the college level—among other places, at Berea, where the craft workshops are still in operation. Today the college has one of the most diverse student bodies in the nation, with all students attending tuition free, as part of a longstanding institutional commitment made possible in part by the college endowment. The workshop program has shifted to reflect this new reality. Last year, Berea College Student Craft invited Stephen Burks, a pioneering African American industrial designer based in New York City, to collaborate on the development of a new product line under the title Crafting Diversity.

Burks has preserved the college’s traditional strengths, such as broom-making and basket weaving, while introducing bold new forms, patterns and colors: a broad palette, representing different perspectives. Students in the program have been encouraged to contribute their own design ideas to the project, and Burks has also devised clever ways for each object to be customized by the students, not just learning and solving problems as they work, but also infusing the results with their own personal creativity. The goal is not just to expand the symbolism of this storied craft program, but also to propel students into lifelong involvement with craft and design. This is one artisanal history that is being reimagined to suit the present day.

* * *

“Where I feel kinship with craftspeople before me is the transformation of tragic circumstances: to make something positive from it.” These are the words of Yohance Joseph Lacour, a Chicago leather artist who is not just a skilled designer and maker but also a successful entrepreneur. Like so many black artisans in the past, he worked hard to get where he is today. Lacour spent nine years of his life in a federal prison in Duluth, Minnesota, eight of them making leatherwork. The craft began simply as a mental escape, but it soon became “a passion to create something from nothing,” he says. Initially, he learned skills from other inmates, some of whom had moved from one jail to another for decades, picking up techniques on the way. Soon it was the other way around: He was inventing his own methods and teaching them to others.

Lacour has been out of prison for about three years and has devoted that time to building his own brand, YJL, making handbags and sneakers. His work reflects his prison experience—in those years he often had to work with scraps and developed an innovative style of collage construction—but his inspiration is primarily from the hip-hop scene that he knew growing up, with its emphasis on improvisation and reinvention. He is constantly developing new shapes, “making leather do things I haven’t seen leather do before,” he said. His viewpoint is unique. “I page through the fashion magazines looking for things I don’t see, bringing it back home to the streets, and taking what I know from the streets aesthetically and cosmically.”

Chicago Couture

Describing himself as “a ‘sneakerhead’ long before the phrase was ever coined,” Yohance Joseph Lacour learned leatherworking and shoe-construction before founding his brand, YJL.

Lacour’s business is growing so quickly that he is exploring the possibility of engaging a manufacturer to execute some of his designs. Lacour is keenly aware of the broader implications of these choices and of his place in a long lineage of black American luxury tradesmen, running back through the pioneer of 1980s hip-hop fashion, Dapper Dan, to the cobblers and seamstresses of the 19th century. He is aware, too, that his life experience reflects a tragic side of African American history, that the contemporary prison system replicates past oppression. (Lacour cites Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness as an important influence.) He has avoided outside investment. Sole ownership represents “a truer freedom for black people,” he says. “Until we have our own, we will forever be in a dependent state.”

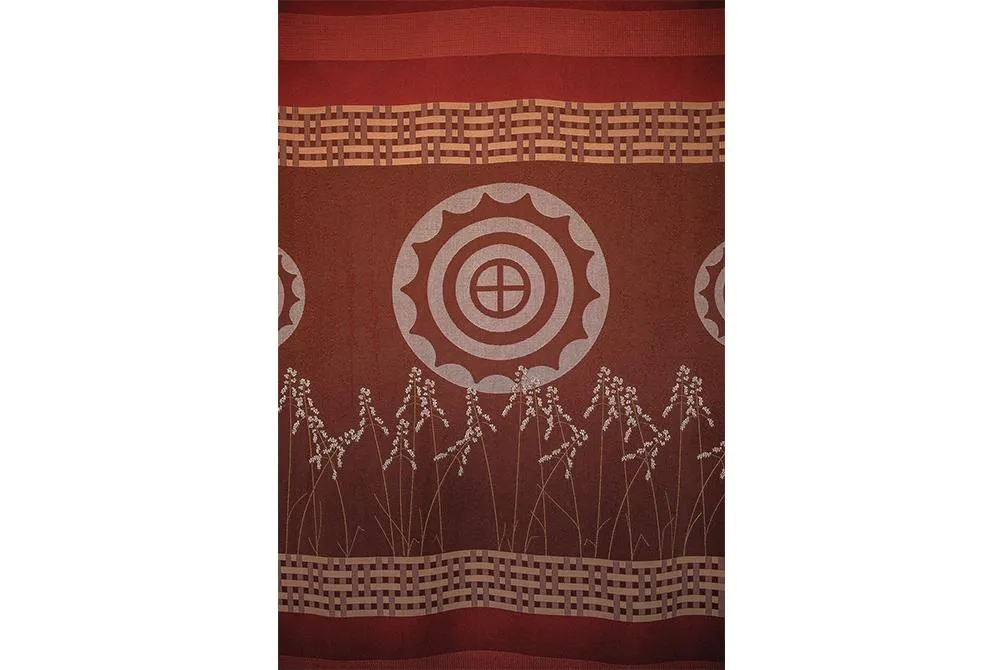

I heard something similar from Margaret Wheeler. She is the founder of Mahota Textiles, based in Oklahoma—the first textile company in the nation owned by a Native American tribe. She shares Lacour’s perception about the intertwining of craft and self-determination. Wheeler, now 77 years old, is of Chickasaw heritage. Like Virgil Ortiz, she grew up in a house filled with crafts. Her mother and grandmother were constantly crocheting, knitting and embroidering, and she took up these skills early in life. For years, she did not think of fibers as her true creative work. But arriving at Pittsburg State University, in Kansas, in the late 1970s, she encountered some great teachers—including the experimental jeweler Marjorie Schick—who exposed her to the possibilities of metalwork and weaving as expressive disciplines.

Wheeler benefited from the surprisingly robust craft infrastructure of the American university system. In the years after World War II, courses in weaving, ceramics and metalwork were widely available in higher education, mainly to accommodate returning soldiers seeking degrees through the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, popularly known as the G.I. Bill. That federal support went almost entirely to white men; they made up the majority of the armed forces, and the black and Native American soldiers who did serve often did not receive the benefits they were due. (Ira Katznelson tells the story in his pointedly titled book When Affirmative Action Was White.) Figures like Charles Loloma, a celebrated Hopi potter and jeweler who attended the School for American Craftsmen on the G.I. Bill, were the exception. It was not until the 1970s, in the wake of the civil rights era and contemporaneous red power movement, that craft courses in American universities started to become more ethnically inclusive.

Narrative Threads

The first textile firm solely owned by a Native American tribe, Mahota belongs to members of the Chickasaw nation, and its goods draw on Chickasaw themes.

After completing her degree, Wheeler became a teacher and then, in 1984, took up weaving full time. She showed her work at Native-oriented museums in the Southwest and presented her work at Indian markets and in fashion shows. She also has experience as a designer for the theater, on one occasion creating the costumes for an all-Chickasaw musical production. Despite her success, it was only thanks to the entrepreneurial spirit and financial backing of her tribe that Wheeler was able to set up Mahota. The company, which specializes in blankets and also makes bags and pillows, is named for her great-great-great-grandmother, who suffered forced removal from ancestral land in the 1830s and ’40s. Even at that early time, indigenous crafts were subjected to a perverse double threat: on the one hand, disrupted by violent assault and displacement; on the other, fetishized as emblems of nostalgia and distorted through the operations of a tourist economy. This troubled history helps explain why, despite the rich tradition of weaving among the Chickasaw and other tribes, it had taken so long for a company like Mahota to exist.

Wheeler’s designs reflect a more affirmative aspect of the past, emulating motifs from ancient Mississippian mound-building cultures, as well as more recent traditions of featherwork, beading and quillwork. Together with Mahota’s business and development manager, Bethany McCord, and the design and operations coordinator, Taloa Underwood, Wheeler has made the leap to factory production. Rather than using hand looms, they collaborate with a custom industrial mill called MTL, in Jessup, Pennsylvania. In addition to the technical advantages this provides—the digital loom literally weaves circles around a traditional loom, executing curves that would be difficult to achieve by hand—it allows them to take on large upholstery commissions and, most important, sell their products for an affordable price. But Wheeler remains a hand weaver at heart. “It’s impossible,” she says, “to understand the structure of the cloth without getting deeply involved in its production.”

* * *

Beginning in the 1940s, a wealthy New York City philanthropist named Aileen Osborn Webb tirelessly worked to build a national craft movement, with its own dedicated council, museum, conferences, school, magazine and network of regional affiliates. Webb’s impact at that time was profound. It was principally thanks to her, and those she rallied to her banner at the American Craft Council, that the studio craft movement flourished in the decades after World War II. While it was a period of prosperity for the country, Webb and her allies were dismayed by what they perceived to be the conformity and poor quality of manufactured goods. Looking to Scandinavia, Italy and Japan, they saw exemplars of a more humanistic, authentic approach. It was not lost on Webb that all of these other countries retained large artisan work forces, and she hoped to foster the same here in the United States.

The problem was that—unlike today—the general population in America saw little value in craft per se. Denmark’s most representative company in these years was the silversmithing firm Georg Jensen. Italy had the skilled glass blowers on the island of Murano. Japan was setting up its Living National Treasure program in the crafts. What did the U.S. have? The auto industry, with its enormous assembly line factories—an economic wonder of the world, and a model for every other branch of manufacturing. What could an individual artisan contribute in the face of that? Webb and her allies did have an answer for this, which they borrowed to some extent from Scandinavia. They called it the “designer-craftsman” approach. The theory was that prototypes would be skillfully crafted by hand, and only then replicated en masse. The problem was that American businesses just weren’t interested. It wasn’t so much that handcraft had no place in their affairs—after all, cars were designed using full-scale clay models. It was the underlying aesthetic of individualism for which manufacturers had little use. Good design might have a certain value, if only for marketing purposes. But the creative vision of an artisan? Where was a corporate executive supposed to put that on a balance sheet?

In the 1960s, the counterculture infused craft with a new attitude, positioning it as an explicit means of opposition to heartless enterprise. Meanwhile, American industry churned along, more or less indifferent to craft, except insofar as management sought to undermine skilled-trades unions. This state of affairs persisted until the 21st century. What finally brought a change seems to have been the internet.

Digital technology is in some ways as far from handwork as it’s possible to get: fast, frictionless, immaterial. Seemingly in response, however, a vogue for crafted goods has arisen. Ethical considerations—a concern for the environment, workers’ rights and the value of buying local—have dovetailed with a more general yearning for tactility and real human connection. At the same time, ironically, digital tools have made small craft enterprises more viable. Online selling platforms turn out to be ideal for telling stories about production, which makes for great marketing copy.

This is not a foolproof formula. Disappointed sellers on Etsy, the internet marketplace for makers, have criticized the company for unfulfilled economic promises, and the parody site Regretsy (slogan: “where DIY meets WTF”), founded in 2009 by April Winchell, showcased egregious examples of craft-gone-wrong. (She closed it after three years, telling Wired magazine, “I’ve said everything I have to say about it, and now we’re just Bedazzling a dead horse.”) With a little hindsight, though, it is clear that communications technology has indeed given the artisan economy a new lease of economic life. It’s now possible to build a business that closely resembles an 18th-century workshop—plus an Instagram feed.

A case in point is the Pretentious Craft Company, based in Knoxville, Tennessee. Founder Matthew Cummings started selling his custom-made glasses on Etsy in 2012 strictly as a “side hustle.” He had gone to art school and thought of himself as a sculptor. But he was also an aficionado of craft beer—one of the artisan success stories of the past decade—and would get together with friends to sample the offerings of a few small breweries. One week, he turned up with handmade glasses, calibrated for maximum enjoyment. As their enjoyment neared its maximum, one of his friends broke down laughing: “Dude, this is so f---ing pretentious.”

The name stuck. Cummings launched the business with just $500 of start-up money—for a while, he bartered his own labor as a gaffer, or skilled glass blower, to get hours of furnace time. At once participating in the microbrewery phenomenon and gently mocking its clichés, Cummings began selling 20 or 30 glasses a month, expanding into the hundreds after he was featured on some larger websites. He moved into his present premises, designed to exacting specifications: shaving off even ten seconds per piece can make a noticeable difference in the bottom line. While everything is still made by hand, albeit using molds, the volume is high, with six skilled blowers at work. Wanting to know more about beer so he could make a better glass, Cummings started a brewery, now its own business venture, Pretentious Beer. Does he miss being a full-time artist? Not much. “Instead of making sculpture my friends and family couldn’t afford, and I couldn’t afford myself,” Cummings says, “I’m making something others can enjoy and interact with on a daily basis. A $35 glass, or a $5 beer, is still an expression of my creativity.” Then too, the prominence of the company allows the team to make ambitious one-off glasses—“the most complicated shapes we can imagine”—which are auctioned online.

Cummings admits that none of the decisions he has made have been strictly about profit: “I have an MFA, not an MBA.” It’s clear the camaraderie of the workshop is the thing he cares about most. That such an undertaking can exist at all, much less find success, says a lot about contemporary America, and the communities of making that can take root here.

The furniture workshop of Chris Schanck, in northeast Detroit, is situated in a squat cinder-block structure, formerly a small tool-and-die company that serviced a nearby General Motors plant.

Built up a century ago, when the auto industry was revving its economic engines, the neighborhood where Schanck works fell on hard times in the 1970s. There are abandoned houses, and city services are erratic at best. In the last few years, though, the area’s residual proficiency at making stuff—and the cheap rents—have attracted creative types. Schanck has an MFA, from Cranbrook Academy of Art, located in the Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills. While a student there, he developed the technique he calls “alufoil.” It begins with an armature, built by hand, which he covers with ordinary kitchen foil. A coat of resin makes the object sturdy, and also brings out the gleam in the aluminum. Schanck has been experimenting and refining the technique.

As Schanck became successful, he needed help. Lots of help. Gradually, his studio has become a sort of community center, with an ethnically diverse crew. Former art students work alongside women from the local Bangladeshi population. (“Welcome to Banglatown,” a neighborhood sign says.) Visit the studio on most days, and you will meet seven women sitting round a large table, placing and polishing bits of shining foil. Their head scarves, shot through with metallic threads, seem almost to declare allegiance to the cause.

Schanck thinks a lot about this business, the livelihoods that depend on it, and the terms on which they are all sustained. When his work is shipped to a New York gallery or to a design fair, the creative energies of the Detroit neighborhood are released into the market. Resources flow back in return, and the cycle keeps going. As amazing as his furniture is to look at, once you see where it is made—this space, with its lively atmosphere of conversation and creativity—the thought may occur that his shop is the true work of art.

* * *

One of the things that has made Schanck’s studio successful is his willingness to take on commissions, which constitute as much as 70 percent of his output. Alongside his purely speculative designs, he has made numerous pieces for museums and private clients. He welcomes the creative friction of this process, which brings “new constraints that I wouldn’t have necessarily given myself before, unanticipated challenges that lead to new areas of research and fresh ways of thinking.”

This is one of craft’s significant competitive advantages over industry: its lifeblood still courses through personal transactions, of the sort that once typified all economic exchange, when every suit of clothes and pair of shoes, every shop sign and household door, was made by hand. Of course, customization of that kind drives up cost, and over the course of American history, cheapness has gradually and decisively won out. We have traded personalization for profusion. This is not necessarily a matter of quantity over quality—mass-produced goods can certainly have an excellence—but it has resulted in a pervasive disconnect between the people who make things and the people who buy and use them. Every craftsperson must decide how hard to push back against this; just how bespoke, and hence exclusive, they want their work to be.

Michihiro Matsuda makes acoustic instruments from his shop in Redwood City, California. Originally from Japan, he trained with the renowned Hungarian-born luthier Ervin Somogyi; in those days, Matsuda’s English was poor, and he learned mostly by watching, just as apprentices have done for centuries. Now, in a typical year, he makes about seven guitars, each one unique, built in close collaboration with his clients. His waiting list is about three years long.

Chris DiPinto lives and works in Philadelphia and makes solid-body electric guitars. An active musician, he originally started making instruments to suit his own playing style (he’s left-handed, which limited his options for a commercially made guitar). He is self-taught—the first instrument he built for himself was made from salvaged oak floorboards. In his busiest years, he has made 400 guitars, while also completing a lot of repair work on instruments brought to his shop.

String Theories

Though their aesthetics and fabrication techniques differ, these luthiers share a deep devotion to artisanship.

Matsuda and DiPinto are a study in contrasts. Matsuda draws inspiration for his exquisite designs from his Japanese background. He has collaborated with maki-e lacquer artists and is known for the distinctive gunpowder finish he sometimes applies to his guitar tops, an adaptation of the traditional scorching that seals the wood of a Japanese koto harp. He also has an avant-garde aspect to his work. His most adventurous guitars resemble Cubist sculptures, with elements deconstructed and shifted from their usual position. The tuning pegboard might end up down at the bottom of the instrument, while the main body is fragmented into floating curves.

DiPinto’s references are more down-to-earth. He loves the classic imported instruments of the 1960s, when the Beatles were big, instruments had sparkle and flash, and kids like him all wanted to be guitar heroes. “To this day,” he says, laughing, “I’m still trying to be a rock star!” Meanwhile, he’s making instruments that other working musicians can afford, using templates, making structural elements and decorative inlays in batches to increase efficiency.

Yet when I described Matsuda’s approach to DiPinto, he exclaimed, “in some ways, I’m just like Michi.” Both still need to consider every design choice in relation to playability and sound, not just looks. And they need to understand their clients. A musician’s identification with an instrument, the physical and psychological connection, is nearly total. So, while DiPinto certainly does have a following—he’s one of the few independent electric guitar makers in the country who has a recognizable brand—he knows that when one of his instruments leaves the shop, it’s no longer about him. Even Matsuda, who makes highly artistic, even spectacular guitars, is clear: “I am not trying to satisfy my ego. I am trying to satisfy my customers.”

* * *

The broader point is that, while craft may be a brilliant showcase for individual talent, it is ultimately about other people. Even the most elite makers, who devote themselves over long years of solitary work, reflect the communities around them. They have to, for a craftsperson who is not trusted will not stay in business long. While craft is a quintessential expression of the American spirit of independence, it is also a way to hold people together.

An exemplar of this principle is Chicago’s blkHaUS Studios, a joint project between the artist Folayemi Wilson and the designer Norman Teague. The unusual name is a play on the Bauhaus, the storied German art and design school, which relocated to Chicago when the Nazis shut it down. The name also says that this is a black creative enterprise devoted to the power of the first-person plural. These values play out in the various aspects of the organization’s work, which is principally dedicated to hand-building structures in wood and other materials to make public spaces more inviting. They have made gathering spaces in a wildlife reserve; furniture for a community garden; even a festival pavilion for the performer Solange Knowles. Perhaps their best-known undertaking is Back Alley Jazz, inspired by neighborhood jam sessions on Chicago’s South Side in the 1960s and ’70s. For this project, they assembled teams of musicians, architects and artists, who together devised settings for pop-up performances in parking lots, churches, yards and—yes—back alleys. They are rolling back the years to the days when the city was a manufacturing center.

Wilson and Teague are highly accomplished in their respective fields, with busy schedules of exhibitions, writing and teaching. But when they work together as blkHaUS, their separate professional identities recede into the background. They encourage collaborators to take a role in shaping a project’s creative vision. Their proudest moment with Back Alley Jazz came three years in, when community members they had been serving simply took over the project. They see this participatory approach as reflecting a specifically black ethic and aesthetic. “The community owns our knowledge,” as Wilson puts it. “If Norman does well, for instance, then everyone owns that well-done.” Accordingly, every blkHaUS project is an opportunity to teach skills to others, showing how craft and design can build cultural equity. “I don’t feel like I’m doing a good job,” Teague says, “unless somebody’s picking up part of what I’m putting down.”

Building Community

blkHaUS Studios in Chicago creates novel settings where people can gather.

Wilson and Teague are not alone in feeling this way. Every maker I spoke to for this article emphasized the importance of passing on skills to others, particularly to the next generation—another way that craft embodies personal vision and public responsibility. John Lavine, the CTE educator in Daly City, California, makes a strong case that teaching craft instills independence: “Devalue the hand and you devalue our sense of self-worth. But take a kid and teach them how to do something with their hands, you teach them to be a citizen that contributes to our culture.” Virgil Ortiz sees craft skill as a building block of Cochiti Pueblo culture, as essential as passing on the actual language. For the same reason Margaret Wheeler, at Mahota Textiles, taught her grandchildren to weave as soon as possible. On one occasion, she remembers, her 9-year-old granddaughter, sitting at the loom at a craft fair, was asked how long she’d been weaving. “Oh,” she replied, “about seven years now.”

Chris DiPinto, who struggled to find anyone to teach him when he was setting out, has at least one person in his guitar shop learning from him at all times, as a matter of principle. Chris Schanck, the furniture designer, says that even the most straightforward commission can be a welcome opportunity to teach methods to new studio members. Matthew Cummings has no illusions about the difficulty of his craft—“it takes about five years not to suck” at glass-blowing, he says—but he loves taking on unskilled trainees, as they have no bad habits to unlearn. And Yohance Joseph Lacour, who began teaching leatherworking almost as soon as he learned it himself, is planning to set up an apprentice program for men and women coming out of prison.

In the end, it’s this combination of ambition, diversity and generosity that most distinguishes the current craft renaissance. The headlong confrontation of perspectives that has lately characterized our public conversations seems to leave no common ground. Maybe craft can provide it? For, wherever you go in the U.S., country or city, north or south, red state or blue, you will find makers, and communities of support gathered around them. It’s an encouraging idea. Yet we must also recognize that, as Lacour puts it, “craft may have brought us together in the past, but it wasn’t a happy union.” Artisanship and inequality have long coexisted.

Here I think of another thing Lacour told me. When he is working with beginning students, he says, he often finds them becoming frustrated, as they try to make their very first shoes—their skills simply aren’t up to the task. In these moments, he’ll say to them gently, “You realize you do get to make another one, don’t you?” The only way to get better is to keep trying. This is the real wisdom of craft: not perfectionism but persistence. And it’s a lesson we all can learn. Craft, at its best, preserves the good in what has been handed down, while also shaping the world anew. This is a reminder that a better tomorrow is always in the making.

Craft: An American History

A groundbreaking and endlessly surprising history of how artisans created America, from the nation's origins to the present day

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/85/f48566de-27ee-4f3d-8bec-69ded2f8fc86/mobile-craft-collage.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/0e/a20ecaf6-57da-49c6-a768-00a86a6b781c/craftv6.jpg)