Still Delightful

A sumptuous show documents how the Impressionists breathed new life into the staid tradition of still life painting

In 1880 the renowned french artist Edouard Manet was commissioned to paint a bunch of asparagus for financier Charles Ephrussi. A collector well known to the Impressionists, Ephrussi had agreed to pay 800 francs (roughly $1,700 today) for the work, but was so pleased with the painting that he gave the artist 1,000 francs instead. Delighted with the higher fee, Manet painted a small picture of a single stalk of asparagus and sent it to Ephrussi with a note that read, "Your bunch was one short."

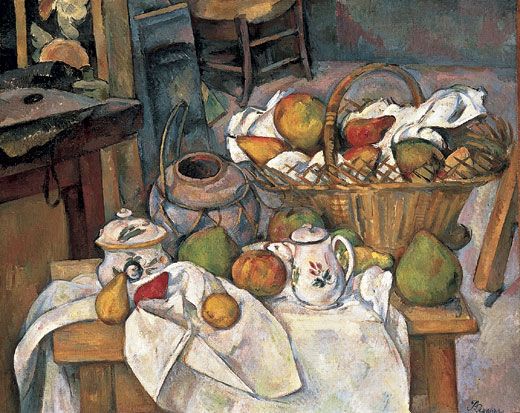

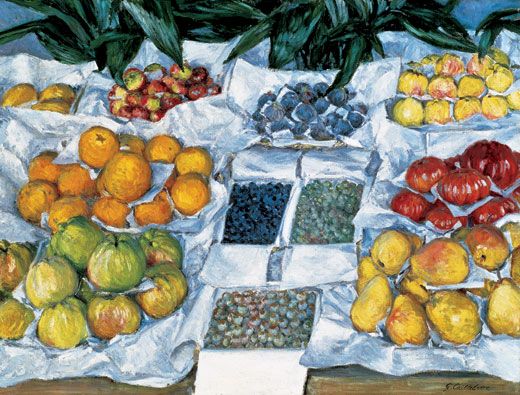

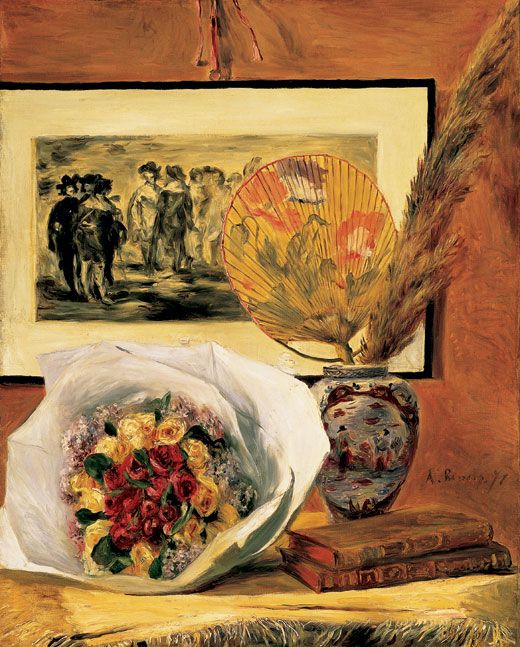

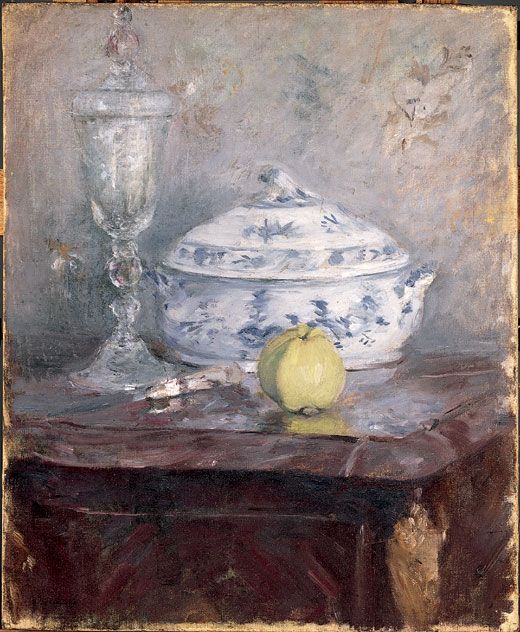

Manet’s luscious painting is just one of the many visual treats featured in a major exhibition on view through June 9 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Organized by Washington, D.C.’s Phillips Collection, where it opened last September, and the Museum of Fine Arts, "Impressionist Still Life" focuses on the period from 1862 to 1904 and tracks the development of Impressionist still life from its beginnings in the realism of Gustave Courbet, Henri Fantin-Latour and Manet through its transformation in the innovative late canvases of Paul Cézanne.

"The Impressionists found in still life a rich opportunity for individual expression," says the Phillips’ Eliza Rathbone, the show’s curator. "They embraced a wider range of subject matter, explored unconventional compositions and points of view, introduced a deliberate informality and reinvigorated still life through their inventive use of light and color."

Whether depicting a simple cup and saucer or a carefully crafted arrangement of household items, the 16 artists in the show infused their paintings with an extraordinary vitality and freshness. They liberated still life from the conventions of the past and brought nuances of personal meaning to such everyday objects as books, shoes, hats, fans, fruit and crockery. "A painter," Manet once said, "can express all that he wants with fruit or flowers."