Stolen: How the Mona Lisa Became the World’s Most Famous Painting

One hundred years ago, a heist by a worker at the Louvre secured Leonardo’s painting as an art world icon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mona-Lisa-Hiest-Italian-Ministry-Public-Instruction-631.jpg)

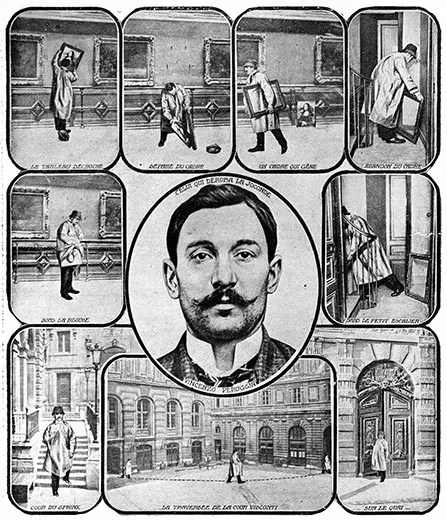

It was a quiet, humid Monday morning in Paris, 21 August 1911. Three men were hurrying out of the Louvre. It was odd, since the museum was closed to visitors on Mondays, and odder still with what one of them had under his jacket.

They were Vincenzo Perugia and the brothers Lancelotti, Vincenzo and Michele, young Italian handymen. They had come to the Louvre on Sunday afternoon and secreted themselves overnight in a narrow storeroom near the Salon Carré, a gallery stuffed with Renaissance paintings. In the morning, wearing white workmen’s smocks, they had gone into the Salon Carré. They seized a small painting off the wall. Quickly, they ripped off its glass shadow box and frame and Perugia hid it under his clothes. They slipped out of the gallery, down a back stairwell and through a side entrance and into the streets of Paris.

They had stolen the Mona Lisa.

It would be 26 hours before someone noticed that the painting was missing. It was understandable. At the time the Louvre was the largest building in the world, with more than 1,000 rooms spread over 45 acres. Security was weak; fewer than 150 guards protected the quarter-of-a-million objects. Statues disappeared, paintings got damaged. (A heavy statue of the Egyptian god Isis was stolen about a year before the Mona Lisa and in 1907, a woman was sentenced to six months in prison for slashing Jean Auguste Ingres' Pius VII in the Sistine Chapel.)

At the time of the “Mona Lisa” heist, Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece was far from the most visited item in the museum. Leonardo painted the portrait around 1507, and it was not until the 1860s that art critics claimed the Mona Lisa was one of the finest examples of Renaissance painting. This judgment, however, had not yet filtered beyond a thin slice of the intelligentsia, and interest in it was relatively minimal. In his 1878 guidebook to Paris, travel writer Karl Baedeker offered a paragraph of description about the portrait; in 1907 he had a mere two sentences, much less than the other gems in the museum, such as Nike of Samothrace and Venus de Milo.

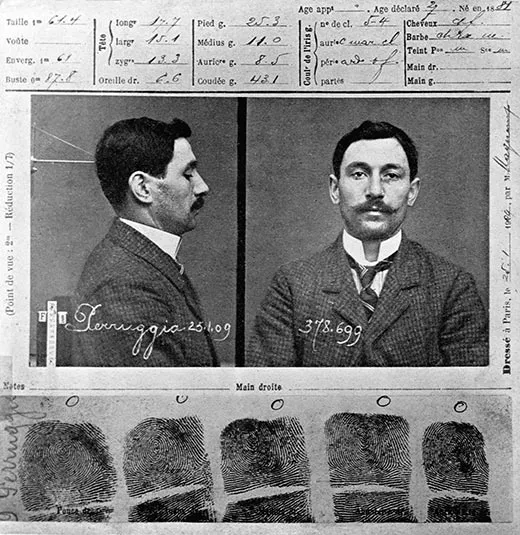

Which isn’t to say it was obscure. A letter mailed to the Louvre in 1910 from Vienna had threatened the Mona Lisa so museum officials hired the glazier firm Cobier to put a dozen of its more prized paintings under glass. The work took three months; one of the Cobier men assigned to the project was Vincenzo Perugia. The son of a bricklayer, Perugia grew up in Dumenza, a Lombardy village north of Milan. In 1907 at the age of 25, Vincenzo left home, trying out Paris, Milan and then Lyon. After a year, he settled in Paris with his two brothers in the Italian enclave in the 10th Arrondissement.

Perugia was short, just 5 feet 3, and quick to challenge any insult, to himself or his nation. His brothers called him a passoide o megloi, a nut or madman. His fellow French construction workers, Perugia later testified in court, “almost always called me ‘mangia maccheroni’ [macaroni eater] and very often they stole my personal property and salted my wine.”

Twice the Parisian police arrested Perugia. In June 1908 he spent a night in jail for attempting to rob a prostitute. Eight months later, he clocked in a week in the Macon, the notorious Parisian prison and paid a 16-franc fine for carrying a gun during a fistfight. He even quarreled with his future co-conspirators; he once stopped speaking to Vincenzo Lancelotti over a disputed 1-franc loan.

Perugia wanted to be more than a construction worker. Appearing in court in 1914 for the theft of the Mona Lisa, he was called a housepainter by the prosecution. Perugia stood up and declared himself a pittore, an artist. He had taught himself how to read and sometimes holed himself up in coffeehouses or museums, poring through books and newspapers.

Stealing the Mona Lisa made sense. Most purloined paintings that were not immediately held for ransom didn't go to a wealthy aristocrat’s secret hideaway, but instead slide into an illicit pipeline being used as barter or collateral for drugs, arms and other stolen goods. Perugia had enough connections to criminal circles that he hoped to barter or sell it.

Unfortunately for Perugia, the Mona Lisa got too hot to hock. Initially, the afternoon newspapers in Paris had nothing on Monday, and the following morning’s papers were also curiously quiet on the matter. Would the Louvre cover it up, pretend it had not happened?

Finally, late on Tuesday, there was a media explosion when the Louvre issued a statement announcing the theft. Newspapers around the world came out with banner headlines. Wanted posters for the painting appeared on Parisian walls. Crowds massed at police headquarters. Thousands of spectators, including Franz Kafka, flooded into the Salon Carré when the Louvre reopened after a week to stare at the empty wall with its four lonely iron hooks. Kafka and his traveling companion Max Brod marveled at the “mark of shame” at the Louvre and attended a vaudeville show lampooning the theft.

Satirical postcards, a short film and cabaret songs followed—popular culture seized upon the theft and turned high art into mass art. Perugia realized that he had not pinched an old Italian painting from a decaying royal palace. He had unluckily stolen what had become, in a few short days, the world's most famous painting.

Perugia squirreled the Mona Lisa away in the false bottom of a wooden trunk in his room at his boardinghouse. When the Parisian police interrogated him in November 1911 as a part of their interviews of all Louvre employees, he blithely said he only learned of the theft from the newspapers and that the reason he was late to work that Monday in August—as his employer had told the police—was that he had drunk too much the night before and overslept.

The police bought the story. Supremely inept, they ignored Perugia and instead arrested the artist Pablo Picasso and the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire. (They were friends with a thief who admitted to pinching little sculptures from the Louvre.) The two were promptly released.

In December 1913, after 28 months, Perugia left his Parisian boardinghouse with his trunk and took a train to Florence where he tried to offload the painting on an art dealer who promptly called the police. Perugia was arrested. After a brief trial in Florence, he pleaded guilty and served only eight months in prison.

Thanks to the high-profile heist, the Mona Lisa was now a global icon. Under a shower of even more publicity, it returned to the Louvre following mobbed exhibitions in Florence, Milan and Rome. In the first two days after it was rehung in the Salon Carré, more than 100,000 people viewed it. Today, eight million people see the Mona Lisa every year.

As soon as the painting was stolen in 1911, conspiracy theories sprouted up. Was it a hoax? Some said the theft was the French government’s way of trying to distract public opinion from uprisings in colonial West Africa. A few months before the painting was found, the New York Times speculated that Louvre restorers had botched a restoration job of the Mona Lisa; to cover this up, the museum concocted the story of an outlandish theft.

Even after the recovery of the Mona Lisa, the world was still incredulous. How could a few Italian carpenters have pulled this caper off by themselves? For years, rumors surfaced that a gang of international art thieves had poached the painting and substituted a fake that was in Perugia's possession when he was caught in Florence. In a 1932 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, Karl Decker, an American journalist, offered a twist: a shady Argentine swindler had arranged for six copies of the Mona Lisa to be made and sold after Perugia’s theft (each buyer thought he had the original).

Two English-language nonfiction accounts of the theft, a 1981 book by Seymour Reit and a 2009 retelling by R.A. Scotti, carry Decker’s story to the hilt, even though there is no supporting historical evidence.

A century has passed since Perugia pinched the painting, and yet historians are still reluctant to give him the credit as the unwitting catalyst for making the Mona Lisa the world-famous icon that it is today.