The Story Behind Thomas Hart Benton’s Incredible Masterwork

The famed artist drew on his extensive travels to paint “America Today”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/67/8567fd54-6ae5-4fd9-a44d-6d4be8ba9dac/dec14_m01_thbenton.jpg)

In a low bluff of salt-crusted and tussocky grass in a corner of Menemsha Pond on Martha’s Vineyard a neatly set flight of stone steps flanked by a retaining wall of fitted boulders leads to a gracefully paved landing, a tessellated slab beneath a foot-deep pool of wind-nudged bubbles. Who shaped this marvelous stairway to the water? Anyone can see that a dedicated and skilled mason with an eye for sculptural symmetry must have made it with his hands, to protect the natural contours of this part of the lovely pond; all the chosen stones have been polished smooth by the sea.

“Daddy did that,” Jessie Benton told me, as I stood admiring its simple beauty and function. Jessie, Thomas Hart Benton’s daughter and younger child, now a dark-eyed and energetic woman of 75, is the embodiment of her parents’ mingled temperaments —the bold Midwestern father, the resourceful Italian mother. “He built the wall, and all that stonework himself, so that we could walk down to our boat or go swimming,” she went on. And then she looked around the pond and glanced up-island, smiling with satisfaction. “This was our world.”

It was Thomas Hart Benton’s world too—this restless man first visited the island in 1920, with his wife-to-be, Rita, and they spent nearly every summer there until his death in 1975, easily earning themselves the hard-won designation as islanders. Given the length of time he spent there, and his paintings of the place that are the sinuous obliquities of a master, he could be ranked next to Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth as a coastal New England painter. The over-simple label of Benton as a Regionalist, one he once embraced himself, misses the point. The ten panels of America Today, his most important mural, show Benton as a painter celebrating (and sometimes critiquing) the whole of American life.

The word mural means “related to a wall,” and calls up the vision of a single oversized painting. This is misleading in the case of America Today, which is a whole painted room, four walls, ten panels, floor to ceiling. Like all great art, the mural does not reproduce well; illustrated it is dim and simplified, its colors untrue, much detail lost. All masterpieces must be seen at firsthand. This was the reason for the Grand Tour. It is the reason that people still visit the great museums of the world and they discover, as I did with America Today, that being in that room, enclosed by those glorious walls, is the way Benton conceived his project: not as a set of pictures but as an enlivened space. It must be seen that way for its subtlety to be appreciated and the full force of its color and vibrancy to be experienced. That is possible now for anyone lucky enough to be in New York City.

In 1929, Benton was asked by Alvin Johnson, director of New York’s New School for Social Research, to do a large-scale mural, which was to be titled America Today—ten panels altogether—for the boardroom of the school’s new Joseph Urban-designed building. The school’s academic program was a departure in higher education, and Benton’s commission was something of a novelty, too. Not only was he to create an ambitious mural that would encompass a room, he also had to agree to do so without compensation—no money, but the materials he needed would be provided. “I’ll paint you a picture in tempera if you finance the eggs,” Benton said, when he was told he wouldn’t be paid. One inducement was that the work, once complete, would enhance his reputation (he was nearly 40 and still struggling), and win him other commissions.

In terms of research he was well equipped. He had been traveling throughout America for the previous four years. “Benton had accumulated all the necessary raw material for a monumental painting of American life in the modern era of rapid change,” art historian Emily Braun writes in Thomas Hart Benton: The America Today Murals. “All he needed was a patron and a wall.”

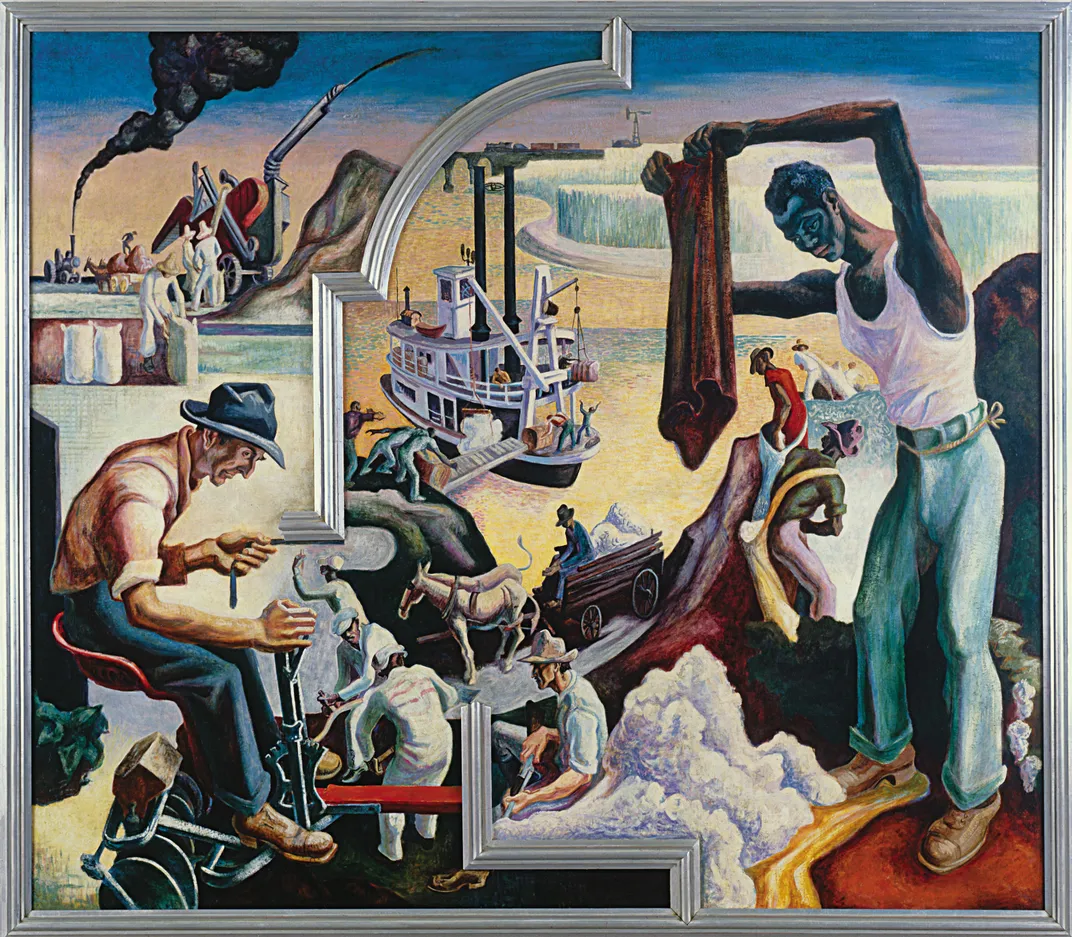

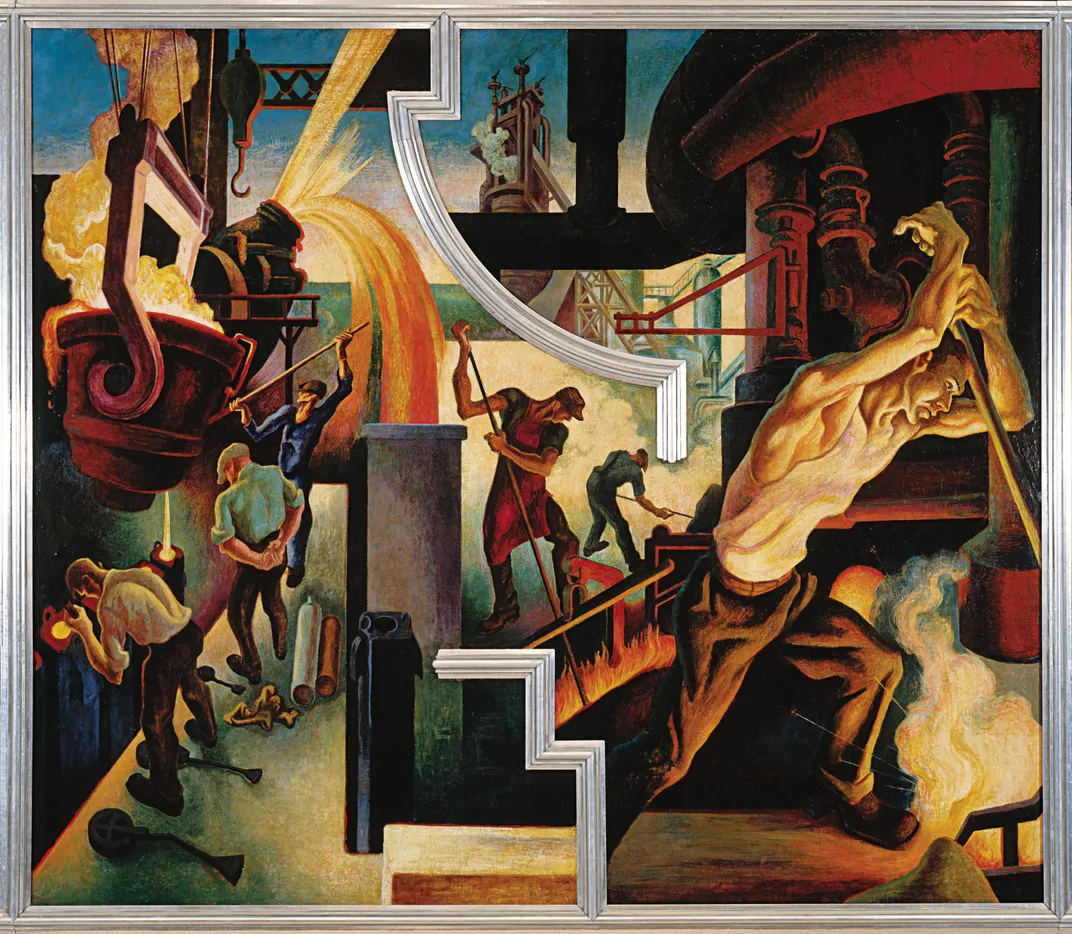

The room in which the mural is now on display, in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is identical in size to the New School boardroom. The sketches and paintings in the adjacent rooms are proof of what Benton said of the veracity of his mural: “Every detail of every picture is a thing I myself have seen and known. Every head is a real person drawn from life.” None of it was fanciful or exaggerated; it is a true portrait of the Jazz Age, which was also the era of intense industrialization in the United States, when cotton was king and oil was beginning to gush; of clearing land for the planting of wheat and cotton, the making of steel and mining of coal, when New York skyscrapers were rising and the city was bursting with life—burlesque shows, movie houses, dance halls, saloons, and in its crowded subways, strap-hanging coquettes stood before seated commuters under signs advertising toothpaste and tobacco.

All this Benton shows in his pictorial chamber. But what of those misshapen torsos and long reaching arms and—a distinct feature of the panels—an incredible variety of human hands: grasping, pleading, holding tools, beckoning, praying, hundreds of hand gestures, scores of bodies with unusual plasticity. Speaking of the Mannerist style of the Dutch painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651), the Met news release helpfully explains how “both artists filled their compositions with undulating, unnaturally elongated figures and diffused the viewer’s attention across the picture plane.”

I move counterclockwise around the room, beginning with “Deep South,” which is largely devoted to cotton, but with contrasting figures, the standing black cotton picker looming over the seated white man on his harrow, the steamboat Tennessee Belle in the center, loading cotton, and the obscure detail, a chain gang being watched by a mean-faced guard cradling a rifle. As in all of the panels the workers are heroic and powerful.

Next to it “Midwest” shows an altered Eden, lumberjacks clear-cutting a forest for timber and for land to grow corn, the grain elevator in the background mirroring the skyscraper depicted across the room in “City Building.” An illustration might not catch the swollen menace of the rattlesnake in the lower left, nor would it show well the boxy Model-T Ford that Benton used in his travels. “Changing West,” the next panel, is an unromantic study of the oil boom in Texas, dominated by thick smoke and a derrick; yet portions of it show the vanishing professions of herdsmen and cowboys, the confrontation (lower center) of a Native American facing a painted floozy.

No humans appear in the central and largest panel, “Instruments of Power,” which is more proof that Benton did not abandon abstraction and that his deftness in rendering movement by controlling color must have impressed his student Jackson Pollock, whose early paintings show Benton’s influence. I don’t think any illustration would do justice to the blur of the whirring propeller, nor is it possible in leafing through a book of pictures to see how the red of the plane is repeated in a man’s red shirt on one panel, a red blouse in another, the red dress of a dancer, or the crimson of the leotard in the trapeze artist flinging herself across the top of the opposite panel. The whole mural, among many other things, is a study in attention-seeking roseate colors.

The red shirt of the work-weary miner in “Coal” seizes the eye, as do the smoke stacks, the fires and the power plant. But you need to stand on tiptoe to see on the upper right the rough shacks of the mining town, a reminder of the humble home where that muscular miner lives. The furnace flames and fire-lit bodies in “Steel” seem to heat the whole painting, and illuminate the strong bodies and gripping hands, but the tiniest grace notes are those of sparks flying.

“City Building” directly across from “Deep South” shows a similar dynamic pattern of workers, black men and white men working together—in both panels the black workers loom larger. An almost imperceptible detail is the sight of two dark-suited figures—gangsters—one handing over money, at the center of the picture.

Sitting at the center of the room, before the two New York panels, “City Activities with Dance Hall” and “City Activities with Subway,” I watch people entering America Today. None of them strode to the facing wall to see “Instruments of Power,” planes, trains and power plants. All the viewers turn to the city panels, where spirit and flesh vied for dominance. They lean to the right to see the burlesque show (“50 Girls”) and the preachers (“God is Love”), or left to see the frenzy of the dance hall, the drinkers, the circus performers. These city panels are the most satisfying of all, the most crowded, the most vital and paradoxical.

Benton appears life-size in that last panel clinking glasses with his patron, Alvin Johnson; wife Rita nearby seated like a Madonna with her son, T.P. In this panel a ticker-tape machine looms near the center, a stockbroker brooding over it, a clue to the Depression that was about to hit hard, as he showed in a rectangular panel over the boardroom door, of human hands—reaching for food, grasping for money. Benton did not know how bad the Depression would be, but throughout this room he was painting the truth, and the truth is timeless and prophetic.

“The Vineyard was his awakening,” Jessie Benton told me.

The Vineyard when he first knew it was still an island of fishermen and dirt roads and ox-carts, a remnant of the 19th-century, where the Bentons eked out a summer existence gathering mussels and clams, Thomas working in his self-built studio, Rita bartering the fluffy rolls she baked for the local farmers’ vegetables. “We weren’t poor,” Jessie says, in an echo of her father’s observation. “We just didn’t have any money.”

The Vineyard was not Benton’s entire world, neither was his portion of the Midwest. His view took in the whole country: Benton was one of the gamest and greatest wanderers in this land, as he documents in his forthright and superbly observed book of travels, An Artist in America (1937). In 1924, after the death of his father, with whom he had a prickly relationship, he decided to travel around the country, “to pick up again the threads of my childhood.” He went down rivers, up mountains, along country roads; camped and hiked and bunked in farmhouses; into the heartland of farms and confronting the cities of roisterers and skyscrapers-in-the-making, obsessively sketching.

Born in 1889, in Neosho, in the lower left-hand corner of Missouri, near the Arkansas uplands that beckoned to him, he knew the mule-drawn plow and the sharecropper’s shack, and he traveled by the clumsiest conveyances —some of the oldest riverboats, by wagon and horseback and old jalopies, and by the steam locomotives he loved and which he hallowed in his work.

He was that ideal creator in the words of Henry James, someone upon whom nothing was lost. He had piles of sketches. He had seen the West, the Deep South, the Midwest, the cities. He had lived in New York, he had recorded the making of buildings, the smelting of iron, the harvest of cotton; he knew from close observation the work of a field hand, the performance of a violinist, the movements of a dancer in a burlesque show, the tedium of a strap-hanger in the subway, the fatigue of a steeplejack. I can’t think of another American painter who knew so well the face of the American landscape and the many forms of the American worker—industrial, agricultural, office clerk, musician, dancer, trapeze artist.

“He is an anthropologist of American life,” his biographer Henry Adams says to me, as we linger over an ink and wash picture of three black farmworkers in a wagon near a cotton shed. Adams has written in detail of Benton’s mission to record forms of work in the United States. (Adams has also in Tom and Jack [2009] detailed the complex relationship between Benton and Jackson Pollock, who was 23 years his junior, his student and for a while an informal member of his household, living for a time in a chicken coop behind the Vineyard house, and painting sunsets and seascapes.) “Benton was a child growing up on the American frontier,” Adams tells me. “There was a way of life that was disappearing, and he wanted to record that.”

“I’m afraid I can’t title it ‘America Today’ anymore,” Benton told Newsweek in 1957. “I’d have to call it ‘What Life was like in America in the Twenties.’” Later, he said, “If it’s not art, it’s at least history.”

It is indisputably art, of a vital kind (“the energy and rush and confusion of American life”), yet not all critics were convinced of that and some still resist acknowledging Benton’s achievement. He has been faulted for being too narrative, or too illustrative, and yet it seems to me, like the great traveler-artists (of whom George Catlin and Edward Lear are good examples), Benton’s art arises from a tradition of storytelling, and reporting from the road. The mural is news; and it is also a mirror of life observed firsthand. As Sinclair Lewis did around the same time in fiction (Main Street, Babbitt, Elmer Gantry), Benton showed us who we were as Americans. Still, the innovations of Benton’s art, and even his subtle abstractions, are lost on some. In his time, he had Marxist detractors; in our time, the late art critic Robert Hughes was the loudest denouncer, accusing Benton of gratuitous dazzle, in effect of being too brilliant.

“Benton was recoiling against the anti-narrative impulse of his time,” the art historian Leo Mazow tells me over a Mexican lunch in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and as for Hughes’ bluster, Mazow says, “Hughes saw criticism in literal terms, as criticizing—rather than describing, interpreting or analyzing.”

You want to say to Benton’s detractors (and carpers or philistines generally): These paintings are not on trial—you are. And his technique, the arrangement of elements in the mural lead the viewer through the work: In his way of connecting the parts to the whole (“a rotogravure style,” Mazow suggests), Benton uses diagonals to direct the eye, X-patterns for focusing activity and subtle balance in the placement of figures. So the eye moves through the narrative, not from left to right, but in a circular way, from figure to figure, deeper into each panel.

The greatest painters and writers teach us how to see. With this in mind, I had decided to visit some sights in the South related to Benton, and happened to be passing through Fayetteville, Arkansas, on my way from Neosho, Missouri. Benton was born in Neosho in 1889 in a grand house that burned down in 1917. It is easy to see how the boy from the small orderly town with its grid of streets surrounded by creeks and gentle hills was energized by the steeper hills and isolated villages farther south in the Ozarks. Neosho is a compact and well-built town surrounded by undulant hills that are still visible today at the far end of its streets.

Among the vintage memorabilia and ephemera displayed by the Newton County Historical Society, near the center of town, is a small news item from the Neosho Times of June 1905, about a fistfight Benton was involved in outside the town’s bank, when he was 16. “Tom Benton and Harry Hargrove had a very interesting ‘scrap’ Sunday evening,” the front-page piece begins. “Both boys were arrested and in police court Monday. The Benton boy admitted he was the aggressor and pleaded guilty to assault.” “He loved to fight,” one of his school friends recalled, when Benton returned for a celebratory homecoming (with Harry Truman) in 1962. His great-uncle was a famous senator with the same name, his father Maecenas a lawyer and congressman, but Tommy (to the despair of his father, whose sternness he resented) grew up a poor student but free spirit. “Neosho had creeks...where we went to swim,” Benton recalled, “and learned the arts of chewing and smoking tobacco.”

Into Arkansas, over War Eagle Creek, and Onion Creek, Dry Fork and past the tiny hamlet of Old Alabam, the Ozarks rise, not mountains but a succession of low ridges, a series of elevations, a sea of long, lumpy hills; no single feature is apparent, there are no peaks, but the whole of it—the broad shifting vista of elongated hills, like thickly forested mesas—the panorama, is dramatic. And it is especially moving because even today it seems unpeopled, the isolated communities hidden in hollows and behind the slopes, some of which are bunchy with old-growth trees.

In Benton’s time as a traveling artist, this was the forest primeval; but even today the Ozarks are remote and beautiful. “And thinly visited,” as I mention to an old-timer in a junk-shop in the hard-up town of Leslie, which was once a prosperous place known for making oak barrels. He replies, “I hope it stays that way.”

This man in his overalls and boots and faded hat has the beaky country profile that occurs frequently in Benton’s sketches of the Ozarks, some of them transferred to the “Deep South” and “Midwest” panels of America Today. On any given morning in the small-town diners in the Ozarks—Harrison, Marshall, St. Joe, Bellefonte and Yellville come to mind—the older men are Bentonesque. In this place of enduring backwoods, the forms of work that Benton recorded are unchanged: family farms, hog-raising, turkey-rearing, cabbage patches.

“Welcome to Hillbilly-ville,” a man says to me on a side street in Alpena, with the self-deprecation that is common in Arkansas. “People are poor here, but that’s a good thing for them. The economy don’t affect them. Up or down, they live just the same.”

This man also mentions that when he first moved to the town from not far away, he had a visit from the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, who had driven over from Harrison, encouraging him to join.

I ask him what his reply was.

“I said, ‘You and me don’t have enough in common for that to happen.’ He took it pretty good and went away.”

Old times there are not forgotten; but not all old-fangledness is salutary. It is worth noting that in significant places in his panels Benton painted black men working harmoniously among white ones, and his sketches are full of the details of black life—the sharecropper, the preacher, the cotton grower. In this unusual landscape, peculiar to Arkansas, among these small farms and their antique plows and harrows, and isolated people, Benton felt like a discoverer. Such is the hardly altered and traditional way of life, and the unspoiled forest, it is still possible to feel that way, and even to sense the same conflicts.

The Buffalo River is the central artery in the heart of the Ozarks. Benton went down the river in the 1920s and again later in his life when he was in his 70s. He followed it on its eastward course to the confluence of the White River, and he continued south.

With Benton in mind, one early

September morning, I rent a boat and paddle for a whole day, from Baker Ford to Gilbert, stopping at intervals to inhale the fragrant air, to watch the sun flashing on the rapids and the insects stirring on the surface of the shallows. The river is greeny gold in the stiller pools, as two deer, a doe and her fawn, pick their way across the river ahead of me, occasionally pausing to nibble or sip. I see herons, and a cormorant; the drumming of a woodpecker echoes from the cliffs and sheer rock faces that make it seem that some parts of the river are coursing through a canyon. In this silence and solitude, I have the reassuring sense—because of the visible slope of the river —that I am sliding downhill.

It is easy to understand why Benton loved his time on the Buffalo River, and why his experience of traveling in the heart of America rekindled the love of the land that he elaborated in his painting. It is one of the achievements of Arkansas environmentalists that the Buffalo River remains untampered with and undammed.

“Interested at the time in my projected history of the United States,” Benton wrote in An Artist in America, “I was looking for some of the old river towns where I might get next to authentic first-hand material.” Soon after, traveling near Natchez, he heard of a location, a levee near the Red River where he might observe an old steamboat—one of the last—being loaded with cotton bales. In Benton’s telling, it was an adventure, finding his way with his friend Bill across the Mississippi to Louisiana, and through the bayous and back roads to the narrower tributary and the Red River Landing.

“I was determined to make drawings of a riverbank loading,” he wrote, “a rare event in these days.” It was a whole week in the heat, under the thorn trees by the river—food and water running low—before the Tennessee Belle appears at the landing for its cargo. This is the boat that is depicted in the center of the panel “Deep South.”

“Y’all came too far,” an older man tells me in the tiny Louisiana farming community (soybeans and sugar cane) of Lettsworth, where he’d been born and never left. “Every time there’s a flood here we get a new channel or two.”

He sends me back upriver, along the levee, past the new canal, and the complex of locks, and some cotton fields looking wintry, thick with blown open tufts, to low-lying woods where I insert myself down a side road. After a few miles on this broken lane, I took a gravel road to the Red River, where I find a landing—perhaps not Benton’s landing, but the shacks, the beached boats, the thorn trees hung with Spanish moss and the air of abandonment combine to make it appear Bentonesque. I have not found the location I’d been looking for, but in the search I’ve found remoteness and beauty.

Benton was seldom on a hunt for something particular. Like all great travelers he launched himself into the unknown, content that he was in the United States—preferring the countryside to the cities—eager to record the life of the land. The fruit of that search can be found in the ten panels of America Today, now restored and rehung, one of our national treasures.

“He has some magic by which he gets to the soul of things,” Henry Adams says to me. We are looking at an oil painting, a portrait of Jessie, done by her father as a present for her 18th birthday—a lustrous portrait of Jessie holding a guitar that she is about to strum. I was thinking how Benton’s genius enabled him to transmute family affairs and discovered pieces of social history into works of art.

“It took him all that summer,” Jessie recalled. And giving a practical meaning to the rosy adjectives “genius” and “magic,” she added, “All his life, Daddy got up early, with the light. He worked all day, until the light went.”