It was late—an indistinguishable, bleary-eyed hour. The lamps in the living room glowed against the black spring night. In front of me was a large dog, snapping his jaws so hard that his teeth gave a loud clack with each bark. His eyes were locked on me, desperate for the toy I was holding. But he wasn’t playing—he was freaking out.

This was no ordinary dog. Dyngo, a 10-year-old Belgian Malinois, had been trained to propel his 87-pound body weight toward insurgents, locking his jaws around them. He’d served three tours in Afghanistan where he’d weathered grenade blasts and firefights. In 2011, he’d performed bomb-sniffing heroics that earned one of his handlers a Bronze Star. This dog had saved thousands of lives.

And now this dog was in my apartment in Washington, D.C. Just 72 hours earlier, I had traveled across the country to retrieve Dyngo from Luke Air Force Base in Phoenix, so he could live out his remaining years with me in civilian retirement.

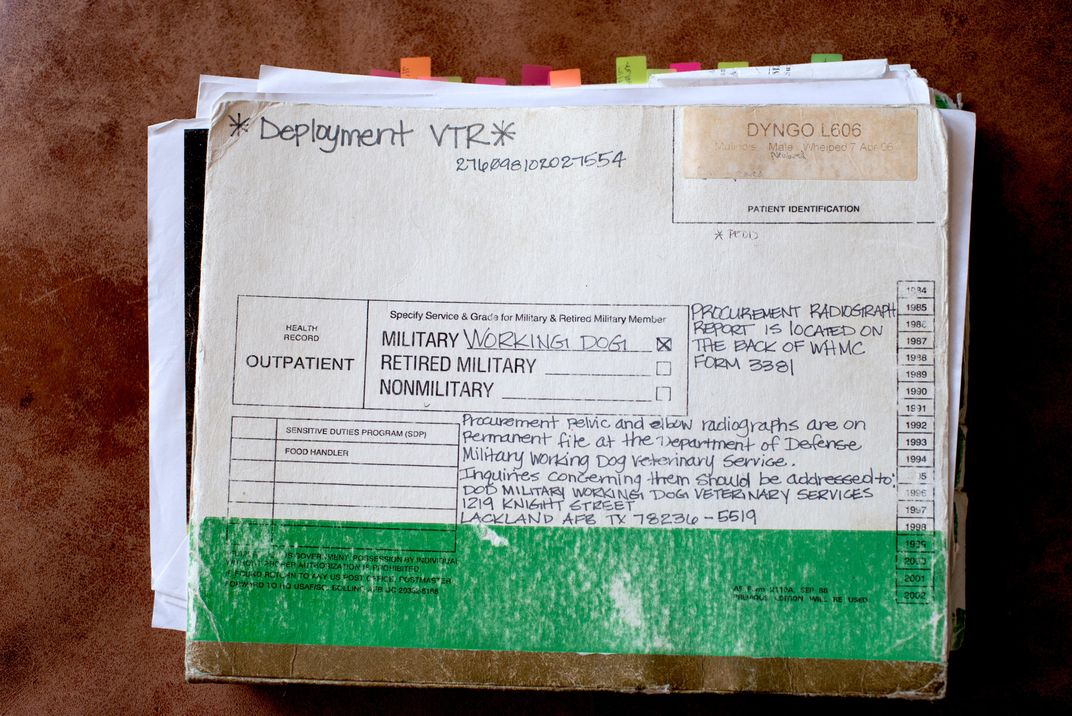

My morning at the base had been a blur. It included a trip to the notary to sign a covenant-not-to-sue (the legal contract in which I accepted responsibility for this combat-ready dog for all eternity), a veterinarian visit for the sign-off on Dyngo’s air travel and tearful goodbyes with the kennel’s handlers. Then, suddenly, I had a dog.

That first night, Dyngo sat on my hotel bed in an expectant Sphinx posture, waiting for me. When I got under the covers, he stretched across the blanket, his weight heavy and comforting against my side. As I drifted off to sleep, I felt his body twitch and smiled: Dyngo is a dog who dreams.

But the next morning, the calm, relaxed dog became amped up and destructive. Just minutes after I sat down with my coffee on the hotel patio’s plump furniture, Dyngo began to pull at the seat cushions, wresting them to the ground, his large head thrashing in all directions. He obeyed my “Out!” command, but it wasn’t long before he was attacking the next piece of furniture.

Inside the hotel room, I gave him one of the toys the handlers had packed for us—a rubber chew toy shaped like a spiky Lincoln log. Thinking he was occupied, I went to shower. When I emerged from the bathroom, it was like stepping into the aftermath of a henhouse massacre. Feathers floated in the air like dust. Fresh rips ran through the white sheets. There in the middle of the bed was Dyngo, panting over a pile of massacred pillows.

Over the course of the morning, Dyngo’s rough play left me with a deep red graze alongside my left breast. On my thighs were scratches where his teeth had hit my legs, breaking the skin through my jeans.

Later, at the airport, with the help of Southwest employees, we swept through the airport security and boarded the plane. The pilot kicked off our six-hour flight by announcing Dyngo’s military status, inspiring applause from the whole cabin. Dyngo was allowed to sit at my feet in the roomier first row, but he soon had bouts of vomiting in between his attempts to shred the Harry Potter blanket I’d brought. I finally pushed it into the hands of a flight attendant, beseeching her to take it as far out of sight as possible—if necessary, to throw it out of the plane.

The trip ended late that night in my apartment, where we both collapsed from exhaustion—I on the couch and he on the floor. It would be our last bit of shared peace for many months.

The following evening, Dyngo’s energy turned into a dawning sense of insecurity. As I cautiously held my ground less than two feet from him, his bark morphed from a yelp to a shout. Then he gave a rumbling growl. That was when my trepidation gave way to something far more primal: fear.

* * *

It was February 2011 when Staff Sgt. Justin Kitts boarded a helicopter with Dyngo. They were on their way to their next mission with the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division on a remote outpost in Afghanistan. Unlike other dogs, Dyngo didn’t shrink away from the beating wind kicked up by helicopter propellers. He bounded in alongside Kitts, hauling himself up onto the seat. As they rose over the white-dusted ridges, Dyngo pushed his nose closer to the window to take in the view. Kitts found a lot of tranquility during these rides together before a mission, just him and his dog, contemplative and still.

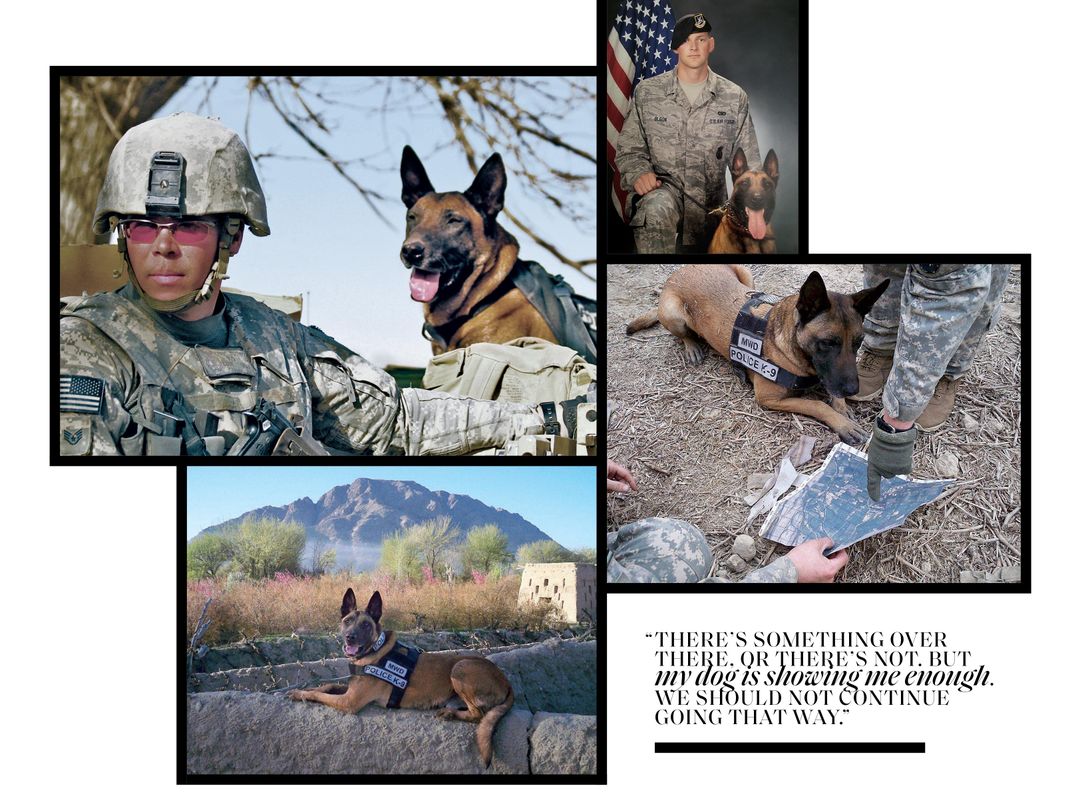

On the first day of March, the air was chilly, the ground damp from rain. Kitts brushed his teeth with bottled water. He fed Dyngo and outfitted him in his wide choke chain and black nylon tactical vest bearing the words “MWD Police K-9.”

The plan for the day was familiar. The platoon would make its way on foot to nearby villages, connecting with community elders to find out if Taliban operatives were moving through the area planting improvised explosive devices. The goal was to extend the safe boundary surrounding their outpost as far as possible. Kitts and Dyngo assumed their patrol position—walking in front of the others to clear the road ahead. After six months of these scouting missions, Kitts trusted that Dyngo would keep him safe.

Kitts used the retractable leash to work Dyngo into a grape field. They were a little more than a mile outside the outpost when Kitts started to see telltale changes in Dyngo’s behavior—his ears perked up, his tail stiffened, his sniffing intensified. It wasn’t a full alert, but Kitts knew Dyngo well enough to know he’d picked up the odor of an IED. He called Dyngo back to him and signaled the platoon leader. “There’s something over there, or there’s not,” Kitts said. “But my dog is showing me enough. We should not continue going that way.”

The platoon leader called in an explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) team. Given the inaccessible location, the team’s arrival would take some time. The other soldiers took cover where they were—along a small dirt path between two high walls in what was almost like an alleyway—while Kitts walked Dyngo to the other end of the path to clear a secure route out. Again, Kitts let Dyngo move ahead of him on the retractable leash. They’d barely gone 300 yards when Kitts saw Dyngo’s nose work faster, watching as his ears perked and his tail stopped. He was on odor again.

If Dyngo’s nose was right, there were two bombs: one obstructing each path out of the grape field. Then the gunfire started. To Kitts’ ears it sounded like small-arms fire, AK-47s. He grabbed Dyngo and pulled him down to the ground, his back against the mud wall. They couldn’t jump back over the wall the way they came—they were trapped.

The next thing Kitts heard was a whistling sound, high and fast, flying past them at close range. Then came the explosion just feet from where they were sitting, a deep thud that shook the ground. Kitts didn’t have time to indulge his own response because just next to him, Dyngo was whimpering and whining, his thick tail tucked between his legs. The rocket-propelled grenade explosion had registered to his canine ears much deeper and louder, the sensation painful. Dyngo flattened himself to the ground. Kitts, knowing he had to distract him, tore a nearby twig off a branch and pushed it toward Dyngo’s mouth. Handler and dog engaged in a manic tug of war until Dyngo’s ears relaxed and his tail raised back into its usual position.

The popping of bullets continued, so, knowing his dog was safe for the moment, Kitts dropped the branch and returned fire over the wall. He’d sent off some 30 rounds when a whir sounded overhead. The air support team laid down more fire and suppressed the enemy, bringing the fight to a standstill.

When the EOD unit arrived, it turned out that Dyngo’s nose had been spot on. There were IEDs buried in both places. The insurgents had planned to box the unit into the grape field and attack them there.

Altogether, during their nine months in Afghanistan, Kitts and Dyngo spent more than 1,000 hours executing 63 outside-the-wire missions, where they discovered more than 370 pounds of explosives. The military credited them with keeping more than 30,000 U.S., Afghan and coalition forces safe and awarded Kitts the Bronze Star.

* * *

I first heard about how Dyngo saved lives in the grape field before I ever laid eyes on him. In 2011, I began researching and writing a book titled War Dogs: Tales of Canine Heroism, History, and Love. I visited kennels on military bases all over the country and had the opportunity to hold leashes through drills, even donning a padded suit to experience a dog attack. I tried to maintain some kind of journalistic distance from the dogs I met on these trips. Many of the dogs were aggressive or protective of their handlers. Some were uninterested in affection from anyone other than their handlers. But there were a handful of dogs I met along the way whose sweet and personable company I enjoyed.

I met Dyngo in May 2012, at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. Though Kitts had recently stopped working as Dyngo’s handler, he’d arranged for them to compete together in the Department of Defense’s K-9 Trials open to handlers from all branches of service. Dyngo went with me willingly when I held his leash and started greeting me with a steady thump of his tail. Back then, his ears stood straight and tall, matching the rich coffee color of his muzzle. Unusually broad for a Malinois, his large paws and giant head cut an intimidating build. Kitts commented that he was impressed with how much Dyngo, usually stoic around new people, seemed to like me. And when Dyngo laid his head in my lap, I felt the tug of love.

It wasn’t long afterward that Kitts asked me if I would ever consider taking Dyngo when the dog retired. He’d always hoped he could bring his former partner home, but his oldest daughter was allergic to dogs. But it would be another three years before the military was ready to officially retire Dyngo and I would have to wrestle with that question for real.

“Are you sure?” my father asked. “It’s a serious disruption, taking on a dog like this.”

My father was the person who’d ingrained in me a love of animals, especially dogs. But now he was dubious. Adopting Dyngo would mean adopting new schedules, responsibilities and costs, including a move to a larger, more expensive dog-friendly apartment. The list of reasons to say no was inarguably long. The more I weighed the decision, the longer that list grew. Even so, that little feeling tugged harder. I weighed all the pros and cons and then disregarded the cons.

I found a new apartment. Everything was set. On May 9, 2016, I was on a plane to Phoenix.

* * *

“You sound scared.”

Instinctively, I gripped the phone tighter. The voice on the other end belonged to Kitts; I’d called him from home as soon as I heard Dyngo growl.

Kitts was right. But I wasn’t just scared, I was really scared.

Kitts counseled me through that night, intuiting that what Dyngo needed to feel safe was a crate. My friend Claire, who has a tall-legged boxer, had a spare crate and came over to help me put together all its walls and latches. I covered the top and sides with a sheet to complete the enclosure. We’d barely put the door in place before Dyngo launched himself inside, his relief palpable and pitiable.

During the first week, I had one objective: to wear Dyngo out. I chose the most arduous walking routes—the mounting asphalt hills, the steepest leaf-laden trails. The pace was punishing. Other challenges presented themselves. Dyngo had arrived with scabs and open sores on his underbelly—just kennel sores, I was initially told. But tests revealed a bacterial infection that required antibiotics and medicated shampoo baths. Since I could not lift Dyngo into the bathtub, four times a week I would shut us both into the small bathroom and do the best I could with a bucket and washcloth, leaving inches of water and dog hair on the floor.

War Dogs: Tales of Canine Heroism, History, and Love

In War Dogs, Rebecca Frankel offers a riveting mix of on-the-ground reporting, her own hands-on experiences in the military working dog world, and a look at the science of dogs' special abilities-from their amazing noses and powerful jaws to their enormous sensitivity to the emotions of their human companions.

Then there was Dyngo’s nearly uncontrollable drive for toys—or anything resembling a toy. Among the former handlers who’d worked with Dyngo was Staff Sgt. Jessie Keller, the kennel master at Luke Air Force Base who had arranged the adoption. Keller offered me a few tips and even offered help with trying an electronic collar (a somewhat controversial training tool that requires experience and care to administer). Her suggestions were thoughtful, but what I was really looking for was a silver-bullet solution. My desperation grew when Dyngo began to twist himself around like a pretzel to clamp down on the fur and flesh above his hind leg, gripping himself in rhythmic bites (a compulsion known as flank sucking).

But something changed when Keller sent me a text message—“If u don’t feel u can keep him please let me know and I will take him back.” In some ways, this was the thing I most wanted to hear. But a resolve took hold: I was not going to give up this dog.

So began the roughly nine months in which Dyngo transitioned into domesticity and I adjusted to life with a retired war dog. During the early months, Dyngo admirably maintained his military duties. As we made our way down the hall from my apartment to the front door of the building, he would drop his nose down to the seam of each door we passed and give it a swift but thorough sniff—Dyngo was still hunting for bombs. Every time I clipped on his leash, he was ready to do his job even if, in his mind, I wasn’t ready to do mine. He’d turn his face up, expectant and chiding. And when I didn’t give a command, he would carry on, picking up my slack.

I tried to navigate him away from the line of cars parked along the leafy streets, where he tried to set his large black nose toward the curves of the tires. How could I convey to him that there were no bombs here? How could I make him understand that his nose was now entirely his own?

His drive for toys—instilled in him by the rewards he’d received during his training—sent him after every ball, stuffed animal or abandoned glove we passed. The distant echo of a basketball bouncing blocks away began to fill me with dread. Giving him toys at home only seemed to amplify his obsession. Finally, seeing no other solution, I emptied the house of toys, though it felt cruel to deprive him of the only thing in his new home he actually wanted.

Struggling for order, I set up a rigid Groundhog Day-like routine. Each day, we would wake at the same hour, eat meals at the same hour, travel the same walking paths and sit in the same spot on the floor together after every meal.

I don’t remember when I started to sing to him, but under the street lamps on our late-night walks, I began a quiet serenade of verses from Simon & Garfunkel or Peter, Paul & Mary. I have no idea if anyone else ever heard me. In my mind, there was only this dog and my need to calm him.

One night that summer, with the D.C. heat at its most oppressive, I called my father. I told him things weren’t getting better. He could have reminded me of his early warnings, but instead he just sighed. “Give it time,” he said. “You’ll end up loving each other, you’ll see.” As Dyngo pulled away from me, straining against my hold on the leash, I found that hard to believe.

My new apartment hardly felt like home. Dyngo didn’t feel like my dog. We weren’t having adventures—no morning romps at the dog park, no Sunday afternoons on a blanket, no outside coffees with friends and their dogs. I didn’t feel like a rescuer. I felt like a captor.

Sometimes, when Dyngo stared at me from behind the green bars of his borrowed crate, I wondered if he was thinking back to his days of leaping out of helicopters or nestling into the sides of soldiers against the chilly Afghan nights. I began to consider the possibility that to this dog, I was mind-numbingly boring. Did he miss the sound of gunfire? Did he crave the adrenaline rush of hopping over walls and the struggle of human limbs between his teeth? What if, in my attempt to offer him a life of love and relaxation, I had stolen his identity, his sense of purpose and, ultimately, his happiness?

* * *

Dogs have been sent to war for a variety of reasons. During World War I, dogs belonging to Allied forces were trained to deliver messages, navigating the trenches and braving bullets, bombs and gas exposure. Back at war a generation later, they recognized incoming shellfire before human ears could hear it. In Vietnam, they found safe passages through the jungles, alerting their handlers to snipers and booby traps. In Iraq and Afghanistan, their extraordinary sense of smell was able to outpace every technological advance made in the detection of IEDs. Altogether, the United States has deployed thousands of dogs to combat zones and, depending on the war, their tours have lasted months to years. When it’s time for war dogs to retire, the law specifies that they should ideally be released into the care of their former handlers. Law enforcement agencies are listed as a reasonable second option—and as a third, “other persons capable of humanely caring for these dogs.”

According to Douglas Miller, the former manager of the DOD Military Working Dog program, adoptions are in higher demand than they were a decade ago. “When I first took this job in 2009, there were about 150 people maybe on the list,” he says. “That list has now grown to about 1,200 or more people.” But not every civilian anticipates the adjustments the dogs will have to make.

“If you ask a family that’s never dealt with a military dog before if they wanted to adopt one, I bet they’d be all about it,” former Marine handler Matt Hatala told me. “But ask them if they want a random veteran who’s been to Afghanistan three times sleeping on the couch, they might be a little unnerved. It’s no different. That dog’s been through situations you’re not going to be able to understand and might not be able to handle.”

Hatala acknowledges that things weren’t always easy after he brought home Chaney, his former canine partner. The black lab was still ready to work, but there wasn’t any work to do. Chaney developed a fear of thunderstorms—which was strange, Hatala says, because he had never before been scared of thunder, or even of gunfire or bombs.

Dogs get to a point where they’re living for their jobs, Hatala says, just like human military service members do. “That has been their identity—that is it—for years and years. And when you get out, you kinda go, ‘What the heck do I do now?’ And you can never really find that replacement.”

Sean Lulofs, who ran the Air Force’s military working dog program from 2009 to 2012, says it took him nearly 15 years to come to terms with his decision not to adopt his own dog, Aaslan. The two had served together in Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004, where the fighting was raw and bloody. “You become so dependent on that dog,” Lulofs explains. Other than a couple of big firefights and some men who were killed, Lulofs says he’s forgetting Iraq. “But I remember my dog. I remember my dog almost every single day.”

When I told Lulofs about my challenges with Dyngo, he asked me as many questions as I’d asked him. One question, in particular, gave me pause: “Did you think that you were deserving of this dog?”

This was a framing I hadn’t considered before. I’d worried I wasn’t giving Dyngo the home best suited for him, but was I deserving of him? Kitts had wanted me to take Dyngo because he knew I loved him, but what if that love wasn’t enough?

Then Lulofs said something that touched the core of that fear: “Don’t ever think your relationship is not as significant just because you didn’t go to war with him.”

* * *

The entrails are strewn everywhere. The remains of his industrial-sized rope toy lie tangled across his front legs. He sits in the midst of it all, panting, grinning, Dyngo the Destroyer. His world now includes toys again. He has learned how to play, maybe for the first time, without anxiety.

It’s now been more than two years since I brought Dyngo home. The borrowed crate was dismantled last year. A big fancy dog bed has become his daytime nap station. His flank-sucking has all but disappeared. All the rugs lie in place, all the couch cushions and throw pillows sit idle and unthreatened.

We are rarely more than a few feet apart—he follows me around, my lumbering guardian. He is now truly my dog.

The force of that love hits me in all kinds of moments—at the sight of his sleeping face, or when he drops his giant head in my lap, closing his eyes and sighing his happiest grunting sigh. Or during the chilling anticipation at the vet when he needed a potentially cancerous cyst biopsied. (It was benign.)

I can take Dyngo out without reservations now. He is gentle with dogs who are smaller or frailer than he is. Much to the shock of his former handlers, he has even befriended a feisty black cat called Sven. We sometimes walk with an elderly neighbor from her car to the building, helping her with her groceries. She holds Dyngo’s face in her hands and coos to him, Mi amor, as she covers his hefty brow with kisses.

Dyngo’s dozen years of rough-and-tumble life are finally catching up with him. His stand-at-attention ears have fallen into a crumple. The marmalade brown of his muzzle is swept with swirls of white and gray that remind me of Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night. He is missing more than a few teeth and it’s not easy to tell if his limp is from arthritis or a degenerative disease that plagues older, purebred dogs like Dyngo.

Every once in a while, as I run my thumb along the velvety inside of his left ear, I’m surprised to see the faint blue of his tattoo: his ID, L606. I trace a finger over the ridge and he exhales a low grumble, but it’s one of deep contentment.

In early 2018, Dyngo and I drove up to my parents’ home in Connecticut. It was an unusual balmy day in February and we rode with the windows down, Dyngo’s head raised into the slanting sun. He adapted well to my childhood home—he made friends with the neighbors’ dogs, dragged branches across the muddy yard and took long evening walks with my father in the downy snow. It was the longest Dyngo had been away from D.C. since he’d arrived in May 2016.

When we pulled into our building’s circular driveway after two weeks, I looked on as he jumped down onto the concrete. His face changed as he reoriented himself to the surroundings, finding his footing along the uneven sidewalks and making a beeline toward his favorite tree spot. As we entered my apartment, he nosed his way inside, then pranced back and forth between his beds and bowls.

He danced toward me, his eyes filled to the brim with an expression that required no interpretation: “We’re home! We’re home!”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(2827x1011:2828x1012)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/fd/65fd3c95-c9a7-4fa4-8496-db00f245aca8/janfeb2019_a01_dyngomwdwardog.jpg)