The Striking New Artworks That Follow Rockefeller Center’s Grand Tradition of Public Art

Frieze Sculpture, on view for just two months, sparks a conversation between works created more than 80 years apart

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/3e/3e3e76bd-61d1-4195-a351-34609b8a1da2/47718151171_d0ef427b1d_k.jpg)

Conceived by John D. Rockefellear, Jr.—fortunate son of the oil magnate—as a city within a city, Rockefeller Center was to be a “mecca for lovers of art,” as he put it, in the heart of New York. He commissioned the installation of more than 100 permanent sculptures, paintings and textiles around his 22-acre real estate development in midtown Manhattan. Since it opened in 1933, artworks like the sculptures of Prometheus and Atlas have become landmarks and photogenic destinations on par with the popular skating rink in its core.

Now through June 28, following a nearly 20-year tradition of mounting one-offs of monolithic, crowd-pleasing contemporary artwork, Rockefeller Center is hosting its most expansive and daring exhibition yet: 20 diverse artworks at once from 14 contemporary artists from around the world. The two-month exhibition marks the New York debut for Frieze Sculpture, an import from the United Kingdom with major contemporary art cred. And the artworks, some commissioned specifically for this show, create a palpable tension with the more permanent artworks installed more than 80 years prior.

Although the exhibition has no unifying theme, a number of artworks are pointedly political, addressing power and inequality by being what Frieze Sculpture’s curator Brett Littman describes as “about speech, about freedom of expression, about media, about the idea of images and then the propagation of images, particularly historical images.”

That pointedness is a radical move in a spot that teems with tourists 24/7 and during the workweek heaves with crowds of corporate types who work for the financial, legal, and other commercial institutions that occupy Rockefeller Center’s skyscrapers.

“I wanted to think about art here very differently,” says Littman, explaining how he chose and sited the artworks. “Generally the art placed here is monumental, with one large piece, usually at Fifth Avenue or at 30 Rock.”

Historian and author of Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center, Daniel Okrent recalls that John D. Rockefeller Jr. was not considered avant garde in the slightest, even though his wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller was a co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art.

“Junior” assigned nearly 40 artists the theme of “New Frontiers” for the permanent pieces commissioned for Rockefeller Center, according to its longtime archivist Christine Roussel, who literally wrote the book—two in fact—on the Center’s permanent art works. These artists delivered, with heavy emphasis on themes of America’s greatness: its spirit, industry, values, assured prosperity and divine providence,.

He was afraid to push boundaries, and when one of the most prominent artists, Diego Rivera, did by including an image of Vladimir Lenin in a mural, Rockefeller famously had it replaced with José Maria Sert’s "American Progress".

“His taste in art was wildly conservative,” says Okrent. “He was a little bit backward.” (The project as a whole wasn’t very well received by the critics of the day when it debuted. As the Gershwin lyric goes, “They all laughed at Rockefeller Center….”)

But of course, the art world, as is its nature, has continued to push many boundaries—of taste, materials, subject matter, and so on—in the decades since, John D. Rockefeller Jr. made his “mecca” for the art he liked best.

“Fortunately, over the past 80 plus years Rockefeller Center management has been open to change and innovation,” Roussel adds, which is what allows the place to be “a vehicle for exciting and sometimes controversial exhibits.”

No more so than with Frieze Sculpture. To get a sense of how much of a departure this new exhibition is for Rockefeller Center, even the diverse array of 192 national flags that normally encircle its sunken skating rink have been removed to make space for a commission of new artwork by Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama. The colorful flags, which represent the United Nations member countries, have been replaced with rough and humble beige ones fashioned out of the jute sacks typically used to transport agricultural products in Ghana. These flags are too thick and heavy to fly, and some flagpoles stand flagless. The work is meant to address the extreme income and resource disparities that exist around the world.

“To me this piece is really about globalization, about capitalism,” says Littman. “This is one of the centerpieces of the whole project.”

Littman says he deliberately chose works that were on a more “human scale” than what visitors have come to expect of Rockefeller Center’s recent contemporary art offerings, and he made a conscious choice to place most of the sculptures directly on the floors and sidewalks, rather than on pedestals and plinths as might be expected. Indeed, it’s nearly impossible not to encounter several of the outdoor artworks if traversing the property.

Steps away from the flags, artist Hank Willis Thomas has created two comic-book style thought bubbles that double as benches, on which people can sit and contemplate the sculpture directly in front of them: Isamu Noguchi’s famous 1940 Rock Center relief “News.” It depicts five “newsmen” (all male) of the Associated Press, which was headquartered there, as heroic figures with one gripping a camera, one a telephone. Taken together, these artworks created nearly 80 years apart highlight the tectonic shift in public esteem towards journalists and journalism—and who has the authority to speak and be heard: Once heroes, journalists in the current socio-political moment, are increasingly under threat of mockery, repression and even violence.

Relatedly, nearby, Chicago-based artist Nick Cave’s oversized bronze gramophone grows from his raised fist, suggesting perhaps the power to activate change through speech or cultural production, like music.

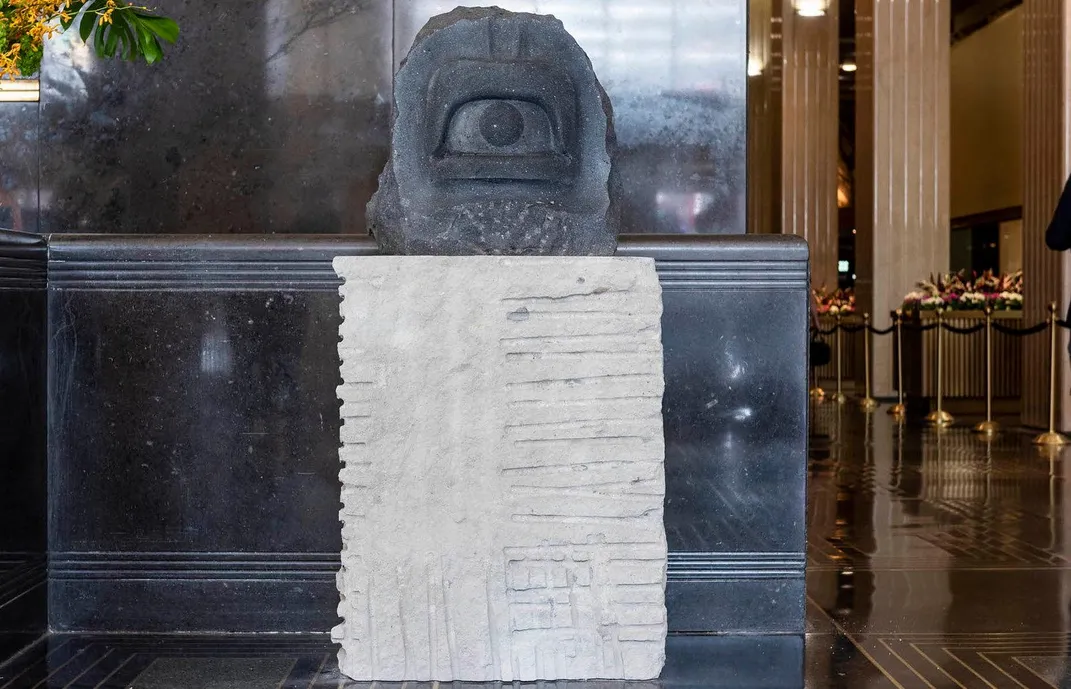

As a further, if subtle, comment on censorship, Littman deliberately placed Mexican artist Pedro Reyes’s two surrealist pre-Colombian-inspired sculptures—one an eye with a tongue sticking out of it, one a mouth with an eyeball—inside 30 Rockefeller Plaza, where Diego Rivera’s original mural stood before it was removed.

Outside the building that is colloquially called “30 Rock,” are two cut-out aluminum sculptures by Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth representing pivotal figures and moments of the American Civil Rights movement. One is of Tommie Smith, the gold-medal winner who raised his fist in a historic Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics, the other is of Ruby Bridges, the six-year old African-American student who was escorted by federal marshals into school because of threats of violence against her during the New Orleans school desegregation crisis. (Bridges was immortalized in one of Norman Rockwell’s most famous paintings, “The Problem We All Live With.”) The way these two sculptures flank the building recalls the robust statues—often of lions and or mounted war heroes—that typically guard hallowed institutions like banks, libraries or government buildings. Along with two smaller-scale representations of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr., these works, says Littman, makes us questions images “that we think we know well…but maybe we don’t” and how society uses certain iconic images, but not others.

The largest-scale work is “Behind the Walls,” a 30-foot tall human head with hands covering the eyes by Spanish artist Jaume Plensa. Cast in white resin, the sculpture comments on what is seen and not seen. “It’s about walls,” Plensa explains, particularly those we put up against taking individual responsibility.

Not all the work is expressly political. To create a conceptual homage to human travel and ingenuity, Littman chose the lobby of 10 Rockefeller Center, once a headquarters for Eastern Airlines, for Polish artist Goshka Macuga’s work. Her two portrait heads of Yuri Gagarin, the first Russian astronaut, and of astrophysicist Stephen Hawking sit in conversation with Dean Cromwell’s permanent 1946 mural "The History of Transportation." Alluding to the materiality of time, artist Sarah Sze’s “Split Stone (7:34)” presents a natural boulder cut open like a geode to reveal a generic image sunset, which Sze captured on her iPhone and then rendered in paint pixel-by-pixel. A piece that is sure to delight young children is Kiki Smith’s "Rest Upon" – a life-sized bronze sculpture of a lamb on top of a sleeping woman. Littman has sited Smith’s work on the walkway between the two lily-filled channel gardens the connect Rockefeller Plaza to Fifth Avenue as a powerful, figurative symbol exploring the relationship between humanity and the natural world.

Also represented at Frieze Sculpture are the artists José Davila, Aaron Curry, Rochelle Goldberg, and the late Walter De Maria and Joan Miró.

The first Frieze Sculpture originated in 2005 as a several-month long exhibition of outdoor sculpture in London’s Regent’s Park timed to the annual U.K. edition of the Frieze art fair. Frieze Sculpture’s debut in New York at Rockefeller Center coincides with art this year’s edition of the Frieze New York, an art fair that draws galleries to New York from all over the world.

Frieze Sculpture at Rockefeller Center includes some on-site talks, tours and other programming, and symbolizes in part a strategic move towards literal and figurative accessibility; tickets to the Frieze fair itself, on view just May 3-5, cost upwards of $57 per adult, and its location on Randall’s Island is not easily reached by public transportation (though the fair does provide some transportation).

**********

For all of John D, Rockefeller Jr.’s aesthetic conservatism, he was uniquely radical in a way that presaged the current exhibition that can be seen in his namesake “city within a city”: a committed allocation of budget for exhibiting and commissioning new work by living artists.

“It was new. It was really not something that there'd been a lot of,” says Okrent. “The commissioning of specific pieces of art was an innovation.”

He added, “And it was part of the plan from the very beginning.”

Frieze Sculpture is free and open to the public for two months (April 26 through June 28) throughout Rockefeller Center, with maps onsite and a downloadable audio guide for iOS users through the Frieze mobile app,