Summertime for George Gershwin

Porgy and Bess debuted 75 years ago this fall, but a visit to South Carolina the year before gave life to Gershwin’s masterpiece

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/George-Gershwin-composing-631.jpg)

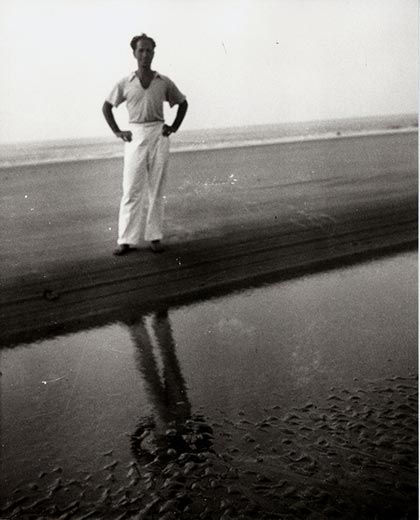

On June 16, 1934, George Gershwin boarded a train in Manhattan bound for Charleston, South Carolina. From there he traveled by car and ferry to Folly Island, where he would spend most of his summer in a small frame cottage. The sparsely developed barrier island ten miles from Charleston was an unlikely choice for Gershwin—a New York city-slicker accustomed to rollicking night life, luxurious accommodations and adoring coteries of fans. As he wrote his mother (with a bit of creative spelling), the heat “brought out the flys, and knats, and mosquitos,” leaving there “nothing to do but scratch.” Sharks swam offshore; alligators roared in the swamps; sand crabs invaded his cot. How had George Gershwin, the king of Tin Pan Alley, wound up here, an exile on Folly Island?

Gershwin, born in 1898, was not much older than the still-young century, yet by the early 1930s he had already reached dizzying heights of success. He was a celebrity at 20 and had his first Broadway show at the same age. In the intervening years he and his brother Ira, a lyricist, had churned out tune after popular tune—“Sweet and Lowdown,” “’S Wonderful,” “I Got Rhythm,” among countless others—making them famous and wealthy.

Yet as Gershwin entered his 30s, he felt a restless dissatisfaction. “He had everything,” the actress Kitty Carlisle once recalled. Still, Gershwin wasn’t fully happy: “He needed approval,” she said. Though he had supplemented his Broadway and Tin Pan Alley hits with the occasional orchestral work—chief among them 1924’s Rhapsody in Blue, as well as a brief one-act opera called Blue Monday—George Gershwin had yet to prove himself to audiences and critics with that capstone in any composer’s oeuvre: a great opera. Initially, he thought the ideal setting would be his home city: “I’d like to write an opera of the melting pot, of New York City itself, with its blend of native and immigrant strains,” Gershwin told a friend, Isaac Goldberg, around this time. “This would allow for many kinds of music, black and white, Eastern and Western, and would call for a style that should achieve out of this diversity, an artistic unity. Here is a challenge to a librettist, and to my own muse.”

But in 1926, Gershwin finally found his inspiration in an unlikely place: a book. Gershwin was not known as much of a reader, but one night he picked up a recent bestseller called Porgy and couldn’t put it down until 4 in the morning. Here was not a New York story, but a Southern one; Porgy concerned the lives of African-Americans on a Charleston tenement street called Catfish Row. Gershwin was impressed with the musicality of the prose (the author was also a poet) and felt that the book had many of the ingredients that could make for a great American opera. Soon, he wrote to the book’s author, DuBose Heyward, saying he liked the novel Porgy very much and had notions of “setting it to music.”

Though Heyward was eager to work with Gershwin (not least because he had fallen on financial hard straits), the South Carolinian insisted that Gershwin come down to Charleston and do a bit of fieldwork getting to know the customs of the Gullah, the African-Americans of the region. The Gullah were descended from slaves who had been brought to the region from West Africa (the word “Gullah” is thought to derive from “Angola”) to farm indigo, rice and cotton on the Sea Island plantations. Due to their relative geographic isolation on these islands, they had retained a distinctive culture, blending European and Native American influences together with a thick stock of West African roots. Heyward’s own mother was a Gullah folklorist, and Heyward considered fieldwork the cornerstone of Porgy’s success.

Gershwin made two quick stops in Charleston, in December of 1933 and January of 1934 (en route to, and from, Florida), and was able to hear a few spirituals and visit a few café. Those visits, brief though they were, gave him enough inspiration to begin composing back in New York. On January 5, 1934, the New York Herald Tribune reported that George Gershwin had transformed himself into “an eager student of Negro music,” and by late February 1934 he was able to report to Heyward: “I have begun composing music for the first act, and I am starting with the songs and spirituals first.” One of the first numbers he wrote was the most legendary, “Summertime.” Heyward wrote the lyrics, which began:

Summertime, and the livin’ is easy,

Fish are jumpin’, and the cotton is high…

The composition of that immortal song notwithstanding, the winter and spring inched along without much progress on the musical. Heyward and the composer decided Gershwin would forsake the comforts and distractions of his East 72nd Street penthouse and make the trek down to Folly Island, where Heyward arranged to rent a cottage and supply it with an upright piano.

The Charleston News & Courier sent a reporter named Ashley Cooper to meet the famous composer on Folly. There, Cooper found Gershwin looking smart in a Palm Beach coat and an orange tie—as though the musician had thought he was headed for a country club.

For a time, the visit to Folly must have seemed like a failed experiment. Even on this remote island, Gershwin showed a remarkable talent for self-distraction. He courted a young widow, Mrs. Joseph Waring (without success), and permitted himself to be conscripted into judging a local beauty contest. He whiled away evenings discussing with his cousin and valet “our two favorite subjects, Hitler’s Germany & God’s women.” He counted turtle eggs; he painted watercolors; he squeezed in a round or two of golf. He enjoyed the beach. As the widow Waring later recalled, “He spent a lot of time walking and swimming; he tried to be an athlete, a real he-man.” Shaving and shirt-wearing both became optional, he soon sported a scraggly beard and a deep, dark, tan. “It’s been very tough for me to work here,” Gershwin confessed to a friend, saying the waves beckoned like sirens, “causing many hours to be knocked into a thousand useless bits.”

When DuBose Heyward came to join Gershwin on Folly, though, the real work began. Heyward brought Gershwin to the neighboring James Island, which had a large Gullah population. They visited schools and churches, listening everywhere to the music. “The most interesting discovery to me, as we sat listening to their spirituals,” wrote Heyward, “…was that to George it was more like a homecoming than an exploration.” The two paid particular attention to a dance technique called “shouting,” which entailed “a complicated rhythmic pattern beaten out by feet and hands, as an accompaniment to the spirituals.”

“I shall never forget the night when at a Negro meeting on a remote sea-island,” Heyward later recalled, “George started ‘shouting’ with them. And eventually to their huge delight stole the show from their champion ‘shouter.’ I think he is probably the only white man in America who could have done it.” (Anne Brown, who would play Bess in the debut production of Porgy and Bess recalled in a 1995 oral history that Gershwin claimed that a Gullah man had said to him: “By God, you sure can beat out them rhythms, boy. I’m over seventy years old and I ain’t never seen no po’ little white man take off and fly like you. You could be my own son.”)

On a July field trip to an African-American religious service in a North Carolina cabin, Gershwin suddenly seized Heyward’s arm as they approached the entrance. The distinctive song emerging from the cabin had entranced Gershwin. “I began to catch its extraordinary quality,” recalled Heyward. A dozen prayerful voices wove in and out of each other, reaching a rhythmic crescendo Heyward called “almost terrifying.” Gershwin would strive to reproduce the effect in Porgy and Bess’ Act II storm scene. “Here, in southern black churches,” writes Walter Rimler in his 2009 biography of Gershwin, “he had arrived at the heart of American music.”

Finally, Gershwin set to work. There followed several months of heightened productivity: “one of the most satisfying and creative periods of Gershwin’s whole career,” assesses Alan Kendall, another biographer. His time in the Carolinas launched the musician on such a spree of creativity that by the beginning of November (now back in New York), he told Heyward that auditioning could soon begin.

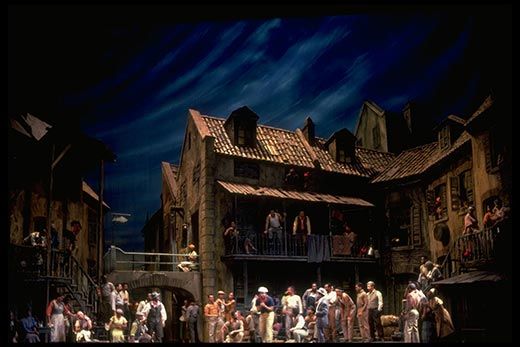

When the opera debuted the following fall, Gershwin had already said, with characteristic arrogance, that he thought it “the greatest music composed in America.” Contemporary critics, however, were divided: those hoping for a Broadway extravaganza found it too highfalutin, while those hoping for something more highfalutin dismissed it as a Broadway extravaganza. Its first run was disappointingly brief. When Gershwin died from a brain tumor in 1937 at age 38, he died had no real assurance of its legacy. He needn’t have worried about its place in the musical pantheon; critics today are nearly unanimous that Porgy and Bess is one of Gershwin’s finest works, if not his masterpiece. The more fraught component of the opera’s legacy has been its treatment of race. Though early critics praised the opera for a sympathetic rendering of African Americans, they lamented that the characters were still stereotyped and this ambivalence persisted through the decades. Seeking to cast the 1959 movie version, Samuel Goldwyn encountered what he called a “quiet boycott” among certain leading men. Both Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier turned down offers, with Belafonte calling some of the characters “Uncle Toms” and Poitier declaring that in the wrong hands, Porgy and Bess could be “injurious to Negroes.”

Later decades were somewhat kinder to the opera, and in 1985, fifty years after its debut, Porgy and Bess was “virtually canonized,” wrote Hollis Alpert in The Life and Times of Porgy and Bess, by entering into the repertory of the Metropolitan Opera. The New York Times called it “the ultimate establishment embrace of a work that continues to stir controversy with both its musical daring and its depiction of black life by…white men.” Such controversy would persist, but Alpert’s ultimate assessment is that African-American opposition to the opera more often than not had to do with “a larger or a current cause” rather than “the work itself.” “Almost always,” he added, “other black voices rose quickly to the defense.”

The question may never be settled entirely, but the opera’s resonance certainly must have something to do with a New York City boy’s working vacation to see the Gullah way of life for himself, one summertime many years ago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)