Summertime for Gershwin

In the South, the Gullah struggle to keep their traditions alive

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/gullah-reunion_388.jpg)

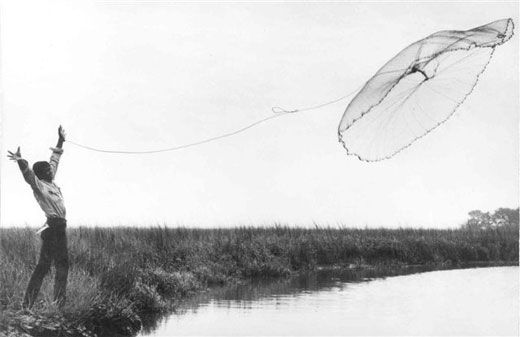

In Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, along Highway 17, a middle-aged African American man sits on a lawn chair in the afternoon sun, a bucket of butter-colored strands of sweet grass at his feet. Little by little, he weaves the grass together into a braided basket. Beside him, more than 20 finished baskets hang on nails along the porch of an abandoned home converted into a kiosk. Like generations before, he learned this custom from his family, members of the Gullah Geechee nation. This distinct group of African Americans, descendants of West African slaves, have inhabited the Sea Islands and coastal regions from Florida to North Carolina since the 1700s.

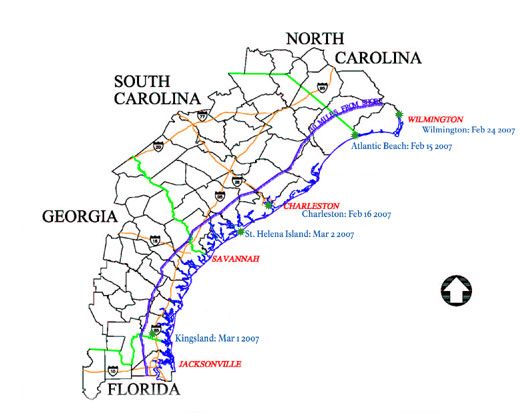

Today sweet grass is harder to come by in Mt. Pleasant. Beach resorts and private residences have restricted access to its natural habitat along the coast. For the past 50 years, such commercial and real estate development has increasingly encroached upon the Gullah and Geechee way of life throughout the South. Now the federal government has passed a Congressional Act to protect their traditions, naming the coastal area from Jacksonville, Florida, to Jacksonville, North Carolina, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor and committing $10 million over ten years to the region. The project is still in its infancy. As the National Parks Service selects a commission to oversee the corridor, the Gullah and the Geechee wait to feel its impact.

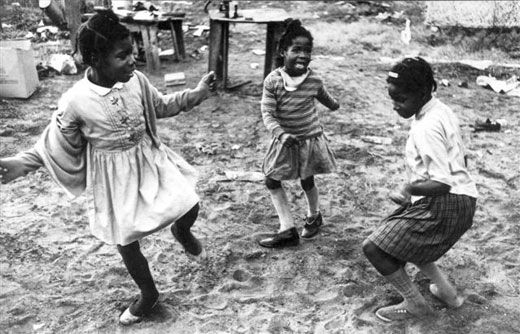

In the early 1900s, long before developers and tourists discovered the area, Gullah family compounds—designed like African villages—dotted the land. A matriarch or patriarch kept his or her home in the center, while children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren lived around the perimeter. The family grew fruits and vegetables for food, and the children ran free under the protective watch of a relative never too far away. They spoke a Creole language called Gullah—a mixture of Elizabethan English and words and phrases borrowed from West African tribes.

Their ancestors had come from places like Angola and Sierra Leone to the American South as slaves during an agricultural boom. Kidnapped by traders, these slaves were wanted for their knowledge of cultivating rice, a crop that plantation owners thought would thrive in the humid climate of the South's Low Country.

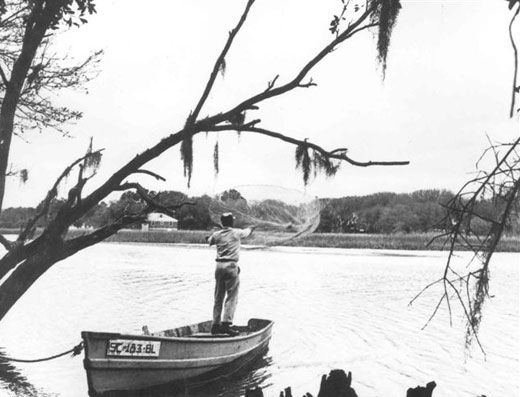

After the Union Army made locations such as Hilton Head Island and St. Helena northern strongholds during the Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman granted the slaves freedom and land under Special Field Order No. 15. The proclamation gave each freed slave family a mule and 40 acres of land in an area 30 miles from the Atlantic Ocean that ran along the St. John's River. The orders, which were in effect for only a year, prohibited white people from living there. The descendants of these freed West African slaves came to be known as Geechee in northern Georgia and Gullah in other parts of the Low Country. They lived here in relative isolation for more than 150 years. Their customs, their life along the water and their Gullah language thrived.

Yet real estate development, high taxes and loss of property have made the culture's survival a struggle. For many years after the Civil War, Gullah land "was considered malaria property. Now it has become prime real estate," says Marquetta Goodwine, a St. Helena native also known as Queen Quet, the chieftess of the Gullah Geechee Nation. "In the 1950s, there started an onslaught of bridges. The bridges then brought the resorts. I call it destruction; other people call it development."

Over the next few decades, construction continued and the Gullah people could no longer access the water to travel by boat. "At first it wasn't bothering anybody. People thought this is just one resort," says Queen Quet. "People started putting two and two together. It was just like our tide. It comes in real, real slow and goes out real, real slow. It's so subtle."

Although many Gullah did not have clear titles to the land, their families had lived there for generations, which enabled their ancestors to inherit the property. Others had free access to areas controlled by absent landowners. As the value of the property heightened, taxes increased, forcing many to leave the area. In other cases, outsiders bought deeds out from under the families.

"A lot of the land that is now being developed was literally taken, and in many instances, illegally," says Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina, whose wife is of Gullah origin. They began not only to lose their homes but also their burial grounds and places of worship. Soon, as waterfront properties became even more valuable, they lost access to the sweet grass, which grows in the coastal dunes of this area.

Had nothing been done to preserve Gullah land and traditions, says Queen Quet, "we would only have golf courses and a few places that had pictures that showed what the Gullah people used to look like." She decided to take action and started the Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition. "When one culture dies, another soon follows. I didn't want to see my culture die."

A Gullah proverb says: Mus tek cyear a de root fa heal de tree—you need to take care of the root in order to heal the tree. Queen Quet intended to do just that when she flew to Switzerland in 1999 to address the United Nations Commission on Human Rights about the Gullah Geechee people. Her speech roused interest in the Low Country community, and the United Nations officially named them a linguistic minority that deserved protection. Over the next few years, the Gullah Geechee people named Goodwine their queen.

Representative Clyburn also became increasingly concerned about his Gullah constituency. "I get to Congress and see all of these efforts being taken to protect the marsh and prevent sprawl," says Clyburn, who in 2006 became the second African American in history to ascend to the position of Majority Whip of Congress. "No one was paying attention to this culture that, to me, was sort of just going away."

In 2001, he commissioned a National Park Service study to look at threats to the Gullah Geechee culture. He then crafted the findings into a congressional act that named the coastal region from Jacksonville, Florida, to Jacksonville, North Carolina, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor.

Only 37 national heritage areas exist in the United States, and "this is the only one that spreads over four states," says Michael Allen of the National Parks Service in South Carolina. He helped Clyburn with the study and is currently selecting a commission made up of representatives from Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina to oversee the formation of the corridor and the allotment of the money. The National Parks Service plans to select the commissioners, who will serve for three years, in May.

Despite the unprecedented congressional act, many Gullah know very little about the corridor. "People who are aware of the corridor are very skeptical of it," says Queen Quet. "They think, 'What do they want? Do they want to help us or help themselves to our culture?'" They have, after all, learned from their past. Although the outside community has shown interest in Gullah traditions by purchasing baskets and taking tours focused on the culture, very few concrete things have been done to help the people. And now that millions of dollars are involved, some Gullah worry that the commission will include profiteers instead of those genuinely interested in helping.

Only time will reveal how the money will be used and what impact it will have on the Gullah Geechee nation. "I hope [the commission] understands the full extent of the law to protect, preserve and continue the culture, and not make it a tourist area, not to have it museumized," says Queen Quet, who has been nominated for the commission. She would like to see the money fund such things as a land trust and heir's property law center, along with historic preservation and economic development. She says, "We need to take ten million seeds and then grow a whole bunch of more plants."

Clyburn's ultimate mission echoes that of nearly everyone involved: "The long term goal is to make sure we keep this culture part of who we are."

Whitney Dangerfield is a regular contributor to Smithsonian.com.