“This is our Sunday church,” says Devin Hosking, a bearded host at Portland, Oregon’s Red Door Meet, a weekly cavalcade of car enthusiasts that has nearly 18,000 followers on Facebook. It’s a cold, rainy day in April, but hundreds of people, mostly in their teens and 20s, descend on a five-block stretch of warehouses to parade their customized rides: spoilers and skirts for better aerodynamics, eye-popping paint jobs, revved engines flaunting added horsepower.

A regular named Matty with a souped-up Subaru tells me there’s a social premium on “built not bought,” so most of these youngsters do their own modifications. “You don’t have to have a nice car,” Hosking says of the open spirit of Red Door Meet, “but you have to care about the culture.”

Custom car culture goes back to the Great Depression, when working-class teens started drag racing on the California salt flats. The racers bought cheap Model T’s and Model A’s, stripped them of unnecessary weight—fenders, bumpers, even front brakes—and hopped up the engines, or swapped them out. Enthusiasm for these “hot rods” spread during World War II, when recruits from California described them to soldiers from other states.

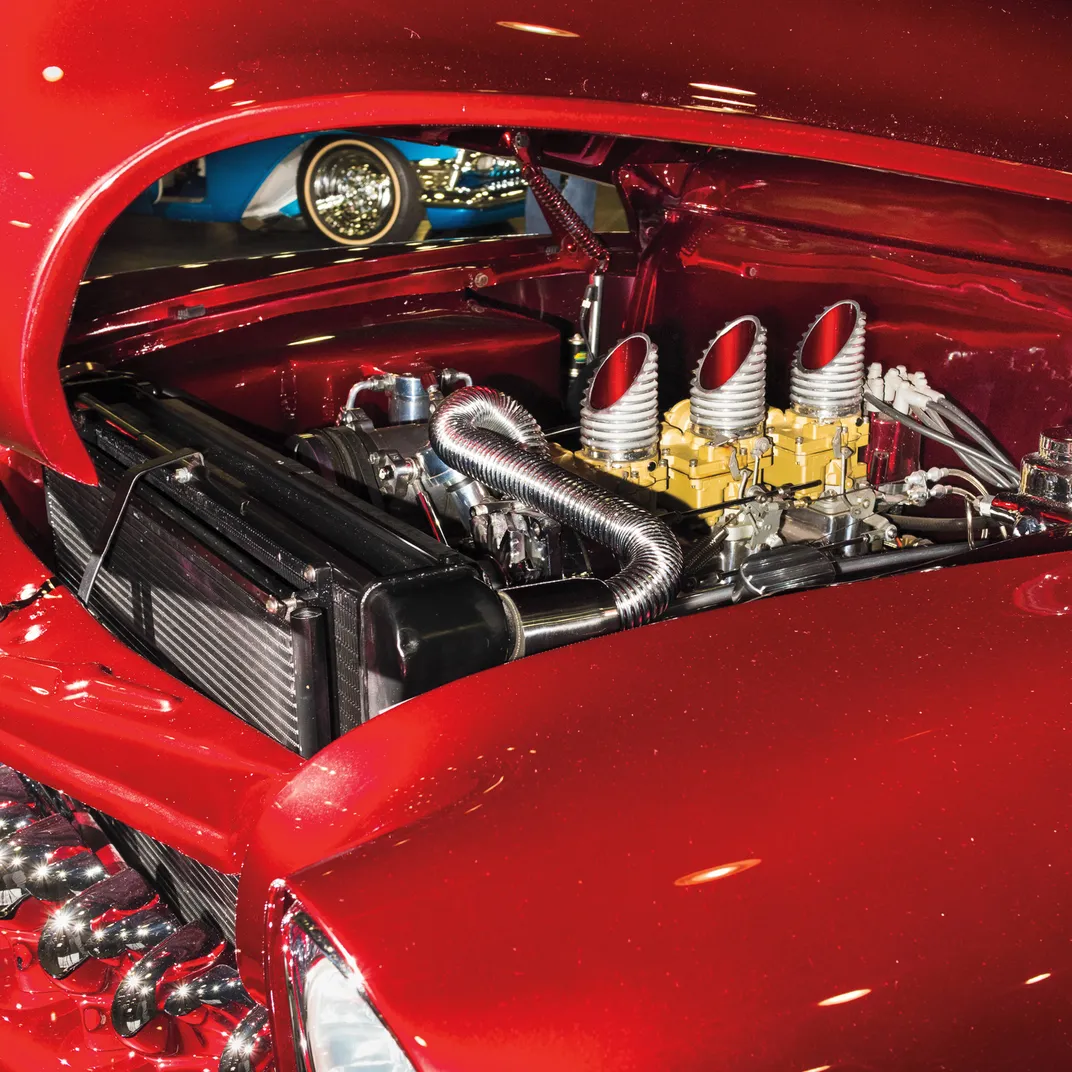

As the first generation of rodders started families and gave up the dangers of the race, some shifted their talents to bodywork. Armed with welding tools, they “chopped” and “channeled” brand-new Chevys and Mercurys—shrinking the tops and lowering the bodies—then “shaved” off exterior parts like chrome trim, emblems and door handles. These sculpted changes gave the new “customs” (often spelled “kustoms”) a distinctive look: sleek, streamlined, even sinister. These cars were designed for show, not for speed. As the custom car enthusiast and author Pat Ganahl put it, “Hot rods raced, customs cruised.”

Teenagers of the 1950s couldn’t get enough of them. “Rods and customs helped teens position themselves against the perceived conformity of the times,” John DeWitt writes in Cool Cars, High Art: The Rise of Kustom Kulture. As parents bought cars straight from the showroom, their sons embraced innovations in paint—candy colors, metal flakes, pinstripes, flames—and gave their cars unique names, such as “Beatnik Bandit,” “Fantom Ford,” and the “Hirohata Merc,” which is often listed as the most famous custom car of all time.

The rockabilly style of that era is still on display at the Portland Roadster Show, an annual tradition since 1956. Many participants today show up with greased hair, black leather jackets and vintage dresses (albeit with more tattoos than their ’50s counterparts). The star of this year’s show was a crimson 1963 Impala covered in chrome and gold-plating that looked like it belonged in the Palace of Versailles. It was a “lowrider,” a style popularized in the 1970s by Latinos in Los Angeles, who took the tradition of “channeling” to a flamboyant extreme, using hydraulics to adjust the car’s height and enable bouncing. “I’ve never seen a lowrider in my life with this much engraving,” the famed customizer John D’Agostino said about the half-million-dollar car.

A humbler crowd favorite was a 1946 International Harvester called “Heeler Hell,” festooned with skulls and intricate woodcarvings created by the owner’s son, who is autistic. Its rusted, unfinished look and exaggerated features were typical of the “rat rod”—a style that emerged in the late 1980s as a revolt against the fancy kustoms that nostalgic baby boomers were buying. One of Portland’s most famous kustoms is “Ratty Caddy,” a menacing ’64 Cadillac decorated with macabre signs, decrepit plush animals and an engine resembling a pipe organ. “I don’t think we allow such cars in buttoned-down Connecticut,” a fan remarked online.

A popular hunting ground for customizers is the annual Portland Swap Meet, the largest event of its kind on the West Coast. Walking through the meet in April was overwhelming: More than 3,500 booths coiled for miles, offering hubcaps, headlights, bumpers, decals and countless other components. Some hawked custom services. One mini-junkyard was labeled “Rat Rod Heaven.” The participants were much older and less diverse than those at the youthful Red Door Meet, but just as friendly. “If you ask one question, you’re committed to a whole conversation,” said my stepfather, who was looking for fog lights for a 1948 Kenworth he’d restored. (My dad is an even bigger car fanatic—I once counted 52 vehicles surrounding our old home in Kansas, including 1950s T-Birds and 1960s Mustangs. He now drives a hot-rod golf cart around the Villages, the largest retirement community in Florida.)

At Manly & Sons, my mustachioed barber raved about the Rose City Round-Up, a kustom festival featuring a drive-in theater, rockabilly bands and a flamethrower-exhaust show. At the Round-Up, held at the Portland International Raceway the third weekend of every June, even the trophies are custom made from car parts.

One of the event’s organizers, Drew Rosa, found parts at the Portland Swap Meet to build a stroller for his son: It is the spitting image of a 1949 Mercury. The little boy, Cash, cruised the festival in his tiny green car, pausing to let a bystander take his photo or a police dog lick his cheek. “The Round-Up is like watching history drive by,” says Rosa, “and seeing kustom kulture live on through another generation.”

:focal(801x416:802x417)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/18/42183c5b-5263-43b2-b1e7-a4d9036677eb/hotrodsdiptych.jpg)