The Art of Video Games

For decades, video games have enthralled and inspired, and now they are the subject of a new exhibit that views them as serious works of art

The Supreme Court ruled last June that video games should be considered an art form, as deserving of First Amendment safeguards as “the protected books, plays and movies that preceded them.” Chris Melissinos reached that opinion some 30 years earlier, as a teenager plugging away at King’s Quest on a neighbor’s PC.

The game’s hand-drawn animation and two-word typed commands seem crude now, but “I remember thinking, ‘Oh my goodness, this is a fairy tale come to life,’” Melissinos says. He still gets goose bumps remembering hidden warp zones in the first Super Mario Brothers.

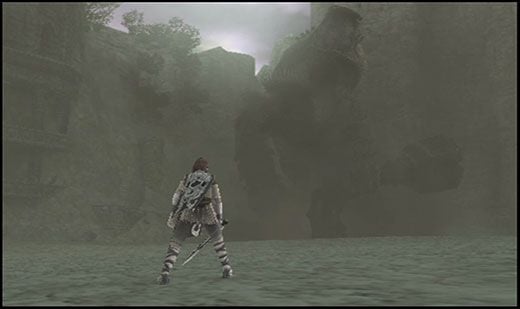

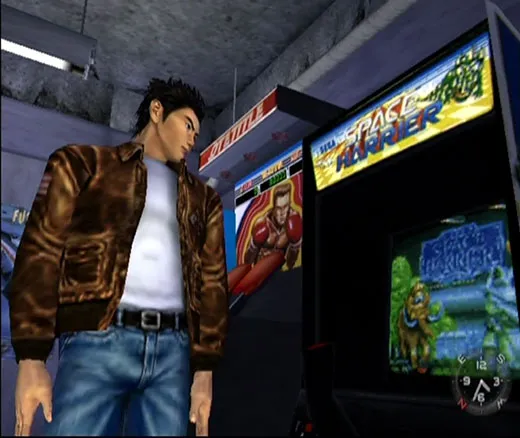

Now Melissinos is the guest curator of “The Art of Video Games,” an exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that celebrates 40 years of the genre, from Pac-Man to Minecraft. The show will include video-game screen shots, videotaped interviews with game designers, vintage consoles from Melissinos’ personal collection (“I’m having a bit of separation anxiety,” he says) and several opportunities for visitors to seize the arcade joystick or PlayStation controls themselves.

Not all of the 80 featured games recall classic film or literature. Attack of the Mutant Camels, for example, stars fireball-spitting dromedaries. Nonetheless, the exhibition, which runs from March 16 through September 30, contends that games offer much more than a chance to mow down armies and plunder cars. Gamers can till fields, build hospitals, steer the wind. They can be inspired to feel guilt or joy or moral ambiguity. They can be transformed instead of just distracted.

Indeed, video games may be the most immersive medium of all, in Melissinos’ estimation. “In books, everything is laid before you,” he says. “There is nothing left for you to discover. Video games are the only forms of artistic expression that allow the authoritative voice of the author to remain true while allowing the observer to explore and experiment.”

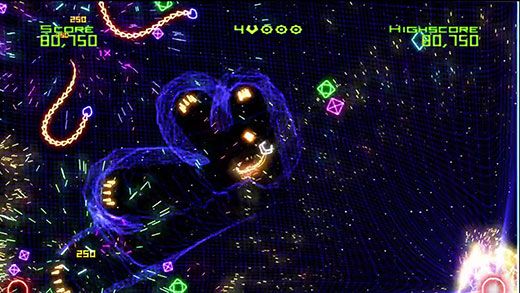

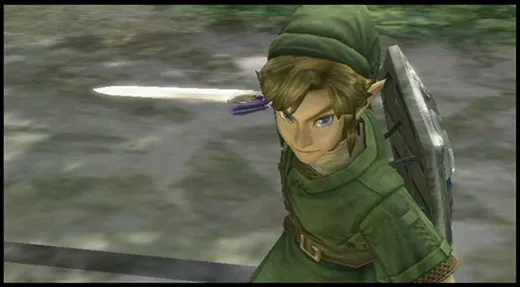

Melissinos grew up with the first games; he later became chief gaming officer at Sun Microsystems, and he is now vice president of corporate marketing at Verisign, a network infrastructure company. He has seen the clunky aliens of Space Invaders and the two-dimensional damsel in distress of Donkey Kong morph into Bioshock and Zack & Wiki. Today drops of animated rain dot computer screens, and characters leave reflections in puddles; it’s like watching cave painting become Impressionism in just a few decades, he says. Games are in many respects converging with movies (which, in their infancy, were also belittled as non-art, Melissinos notes). Designers employ photo-realistic environments and motion-capture technologies and commission original scores.

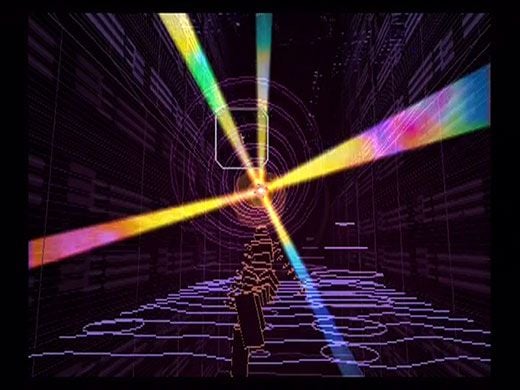

Yet Melissinos also embraces more primitive examples of the genre. Older games are sociologically revealing: Missile Command, Melissinos says, exemplifies cold war thinking. More important, the stripped-down early games capture the essence of the art form. Since early graphics and narratives were so limited, players had to draw heavily from their imaginations to make the scenarios come alive, becoming what Melissinos calls the game’s “third voice” (along with the designer and the mechanics of the game itself).

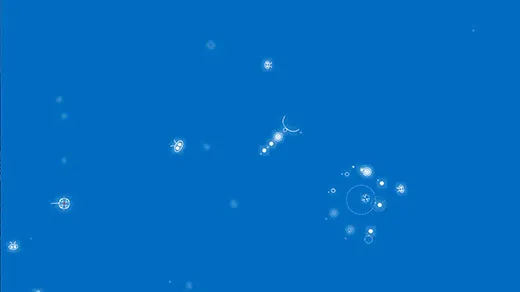

Visitors will have a chance to play Flower, which has been hailed as an almost sublime experience involving an apartment flower’s “dream” of nature. Designer Jenova Chen came up with the concept while driving from Los Angeles to San Francisco on Interstate 5 one day in 2006 and seeing “endless green hills, blue skies.” A Shanghai native unused to such sights in nature (“It kind of reminded me of the Windows wallpaper,” he says), he tried to photograph the scene with his cellphone, then to capture it on video. But “I can smell the grass,” Chen recalls. “I can feel the wind. I can hear the sound of the grass waving. You just can’t capture that with video. The only way I can capture the truth in this place and this feeling is by artistic exaggeration.” So he began writing code for some 200,000 blades of 3-D grass.