The Banana King, Surviving K2, the Allure of America and More Recent Books

The man who helped make the banana an American favorite also mercilessly used his company’s power to topple foreign governments

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Books-Banana-King-631.jpg)

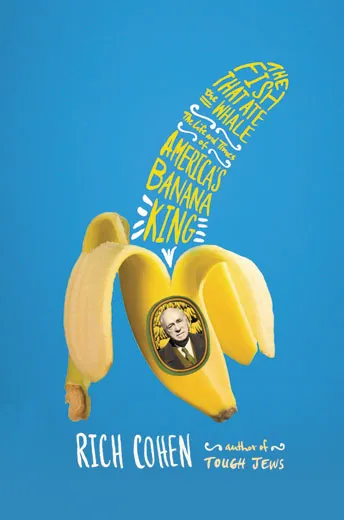

The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King

by Rich Cohen

Americans eat some 20 billion bananas a year, more than apples and oranges combined. But it wasn’t always so—at the end of the 19th century, few people in the United States had ever seen a banana, much less tasted one. The once exotic fruit owes its ubiquity to one man, Samuel Zemurray—Sam the “Banana Man,” a Russian immigrant to New Orleans who gambled on the freckled bananas other companies discarded, getting them to market before they turned to mush. He built a mini-empire of his own, then merged with the industry juggernaut, United Fruit. In 1933, he engineered a corporate coup that landed him atop the massive company; his New York Times obituary would call him “the fish that swallowed the whale,” whence the awkward title of Rich Cohen’s sly biography.

It’s difficult today to imagine the power of United Fruit. It was one of the first “truly global” corporations, writes Cohen, as prevalent as Google and “as feared as Halliburton.” A revolving door between its executive suite and the U.S. government made it “hard to distinguish United Fruit from the CIA” in the 1940s and ’50s. When the company sensed hostility in Guatemala—where it owned 70 percent of all private land by 1942—it mounted a PR campaign warning of a dangerous Communist presence. Not long after, Guatemalans bid farewell to their democratically elected president, Jacobo Árbenz—“Operation Success” the CIA called it. In 1961, the U.S. government borrowed United Fruit’s guns and ships when it sent a band of Cuban exiles into the Bay of Pigs. The company’s 115 ships, Cohen writes, made up “one of the largest private navies in the world.”

Cohen focuses on Zemurray’s expansion into Central America, and the book’s semi-secret plots make it read more like a mystery than the biography of a businessman, with characters plotting military overthrows in back-alley bordellos. But the Banana Man’s ascent raises broad questions. Was Zemurray a rapacious conquistador or a great American businessman? The line, Cohen shows, is blurry. We cheer the hustling immigrant’s entrepreneurial spirit but regret his tactics. The fruit wasn’t the only thing almost rotten.

Zemurray, who ran United Fruit for nearly three decades, was a shadowy figure, and Cohen acknowledges the limits of his research. But this doesn’t stop him from making some bold claims: “If you want to understand the spirit of our nation, the good and bad, you can enroll in college, sign up for classes, take notes and pay tuition, or you can study the life of Sam the Banana Man.” An overstatement, of course. But there’s a lot to learn about the seedier side of the “smile of nature” in this witty tale of the fruit peddler-turned-mogul.

Buried in the Sky: The Extraordinary Story of the Sherpa Climbers on K2’s Deadliest Day

by Peter Zuckerman and Amanda Padoan

It’s a testament to the thrills in this book that I scoured the notes, eager to learn how the authors wrote their account of the 2008 disaster that claimed the lives of 11 people on K2. To describe the summit of the world’s second-highest mountain, which straddles China and Pakistan, they “had the characters take us to locations with a similar look and feel” and “reenact what happened.” As one of the few people who haven’t read Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air, I had little knowledge of what a gruesome affair climbing could be. This book makes it clear. Climbers drown in avalanches of snow, toes are lost, limbs are severed. One man’s skin, after returning from the trek, had turned to “the consistency of cheese.”

Zuckerman, a journalist in Portland, Oregon, and his cousin Padoan, a climber, set out to portray the high-altitude porters who risk their lives so wealthy Westerners can risk theirs: the porters’ unique physical capabilities, their belief in the spirits that inhabit the mountain, their motivation. “He had paid us some money,” one porter says, “so we acted as though he owned our lives.” The book also explores the tensions between the Sherpas—a Nepali ethnic group renowned for extreme climbs—and the Pakistani porters. But the authors’ commendable documentary about the people who carry the gear is overtaken by the chilling adventure story of one terrible day on the mountain.

Bunch of Amateurs: A Search for the American Character

by Jack Hitt

A spirit of playfulness permeates this book, which argues that amateurism—pursuits motivated by love over obligation—is what makes America, well, America. “The amateur’s dream,” Hitt writes, “is the American dream.” It’s entirely appropriate that Hitt, perhaps best known for his appearances on “This American Life,” skips merrily from one subject to the next. Anyone can be an expert—why confine yourself to what you already know? A chapter on make-do chemists fiddling around with DNA extraction follows one on the ivory-billed woodpecker. He’ll crawl among the Gungywampers in Connecticut—old stone huts that some people argue are Celtic homes—and hunker down with a raver trying to make glow-in-the-dark yogurt. Among his examples are genuinely inspiring tales—underdogs who get their due and show the stuffy experts. What could be more American than that? And in an era when the once unassailable Encyclopaedia Britannica is in decline as the open-source Wikipedia gains legitimacy, he just might be on to something.

Prairie Fever: British Aristocrats in the American West 1830-1890

by Peter Pagnamenta

Despite the British Empire’s reach, it was America that captured the aristocrat’s imagination in the 19th century, says historian Peter Pagnamenta. The great West evoked Romantic poetry and seemed a portal to an earlier time—an Eden, an arcadia, where land was limitless, not parceled out by primogeniture. Pagnamenta follows several grandees in their travels, and his slice-of-society approach captures the appeal—the mighty buffalo! the wide-open space!—that propelled these adventurers back and forth across the Atlantic at a time when the U.S. elite had little interest in their own backwoods. There were never more than a few thousand wealthy Brits roaming the prairies, but they had “significance far beyond their number,” he writes, and they represented a lingering desire to own part of America. One Irishman built a 1.3 million-acre ranch in Texas for 100,000 cattle with his American partner. The Marquis of Tweeddale lorded over 1.75 million acres in Texas. By 1884, foreign “noblemen” owned almost 21 million acres of American land—the equivalent of a ten-mile-wide strip coast to coast. But a public outcry led Congress in 1887 to pass the Alien Land Bill, preventing foreign prospectors from owning land in the Western territories unless they declared their intention to become U.S. citizens. Not until then, writes Pagnamenta, was it “finally realized that the Far West could never be part of the British Empire.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)