The Cherished Tradition of Scrapbooking

Author Jessica Helfand investigates the history of scrapbooks and how they mirror American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/scrapbooks-delineator-631.jpg)

Graphic designer Jessica Helfand has been fascinated with visual biography since her days as a graduate student in the late 1980s, pouring over Ezra Pound’s letters and photographs in Yale’s rare book library. But the “incendiary moment,” as she calls it, which really sparked her interest in scrapbooks came in 2005, when she wrote critically of the hobby on her blog Design Observer. Helfand derided contemporary scrapbookers as “people whose concept of innovation is measured by novel ways to tie bows,” among other things, and was vilified by the craft’s enthusiasts. “I hit a nerve,” she says.

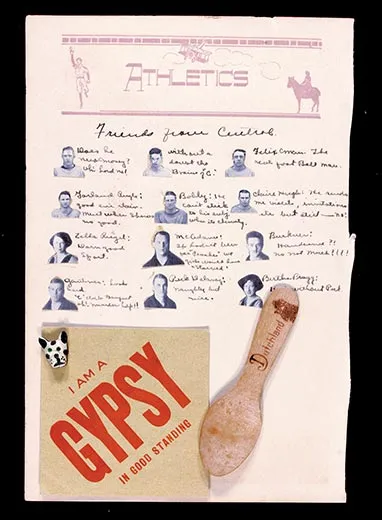

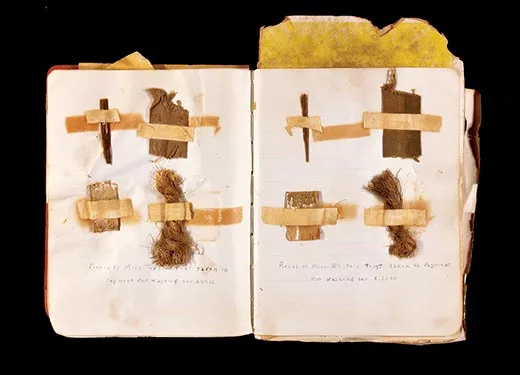

Spurred on by the rise of scrapbooking as the fastest growing American hobby, Helfand set out to study the medium, collecting, from antique stores and eBay auctions, over 200 scrapbooks dating from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the present. In the collages of fabric swatches, locks of hair, calling cards and even cigarette butts pasted on their pages, she found real artistry. Helfand’s latest book, Scrapbooks: An American History, tells the story of how personal histories, as told through the scrapbooks of civilians and celebrities, including writers Zelda Fitzgerald, Lillian Hellman, Anne Sexton and Hilda Doolittle, combine to tell American history.

What types of scrapbooks do you find the most interesting?

The more eclectic. The more insane. Scrapbooks that are pictures of just babies and cherubs or just clippings from the newspaper tend to interest me less. I like when they’re chaotic the way life is.

What are some of the strangest things you’ve seen saved in them?

Apparently it was custom in the Victorian age for people to keep scrapbooks just of obituaries. And they are weird obituaries, like one in which a woman watches in horror as streetcar claims the life of her six children. Incredibly macabre, gruesome things. We have one of these books from 1894 in Ohio, and in it there is every weird obituary. “Woman lives with remains of daughter for two weeks in a farmhouse before she’s discovered.” Just one after another, and it’s pasted onto the pages of a geometry textbook.

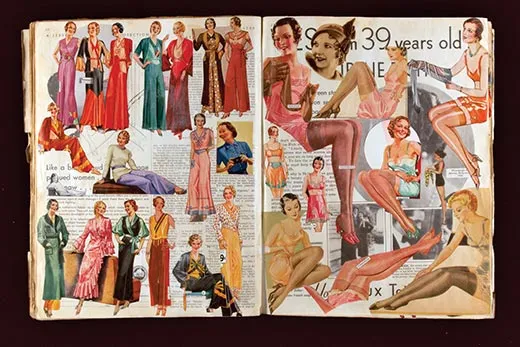

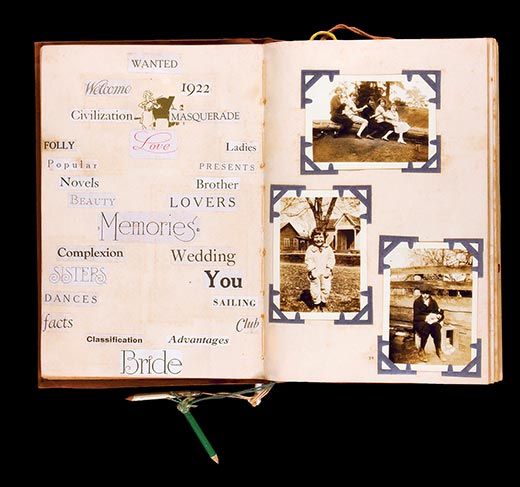

You see often in books by college and high school girls these bizarre juxtapositions, like a picture of Rudy Valentino next to a church prayer card, or a box of Barnum’s animal crackers pasted right next to some steamy, embraced Hollywood couple for some movie that had just come out. You could see the tension in trying to figure out who they were and what their identities were vis-à-vis these emblems of religious and popular culture. I’m a kid, but I really want to be a grownup. There’s something so dear about it.

What do you think goes through people’s minds as they paste things?

In antebellum culture just after the Civil War, there was this kind of carpe diem quality that pervaded American life. I have my own theory that one of the reasons for the rise in scrapbooking has been so meteoric since 9/11 is precisely that. People keep scrapbooks and diaries more during wartime and after wartime, and famine and disease and fear. When you feel an increased sense of vulnerability, what can you do to steel yourself against the inevitable tide of human suffering but to paste something in a book? It seems silly, but on the other hand, it’s quite logical.

Scrapbooks, like diaries, can get pretty personal. Did you ever feel like you were snooping?

I took pains not to be prurient. These people aren’t here to speak for themselves anymore. It was very humbling to me to think about the people who made these things in the moments that they made them, what they were thinking, their fears and trepidations. The Lindbergh kidnapping, the Hindenburg, all these things were happening, and they were trying to make sense of it. You fall in love with these people. You can’t have emotional distance. I wanted to have some analytical distance in terms of the composition of the books, but certainly when it comes to the emotional truths that these people were living with day by day, the best I could do was just be an ambassador for their stories.

How do scrapbooks of famous and non-famous people slip through the cracks and not end up with their families?

The reason scrapbooks secede from their families is that there are typically not children to keep them. Or it’s because the kids didn’t care. They’re old, falling apart. To a lot of people, they’re really forgettable. To me, they’re treasures.

But the other thing is the more curatorial, scholarly angle. There tends to be a very scientific, quantitative view of gathering evidence and then telling the story chronologically. These things just fly in the face of that logic. People picked them up, put them down, started over, ripped out pages. They’re so unwieldy. Typically historians are more methodical and meticulous in their research and in their compilation of stories. These things are the opposite, and so they were relegated to the bottom of the pile. They would just be anecdotally referenced, but certainly not held in point as really reliable historical documents. My editor tells me that there’s a more open mindedness to that kind of first person history today, so I may have written this book at a time when it could be accepted on some scholarly level in a way that it couldn’t have 20 years before.

What was it like paging through poet Anne Sexton’s scrapbook for first time, seeing the key to the hotel room where she spent her wedding night?

It’s the most adorable, clumsy, newly wed, young, silly thing. It’s just not what you associate with her. Those kinds of moments were certainly exciting for me in terms of finding something I didn’t expect to find that was so out of sync with what the record books tell us. It was sort of like finding a little treasure, like you were going through your grandmother’s drawers and you found a stack of love letters from a man who wasn’t your grandfather. It had that kind of quality of discovery. I loved, for example, the little firecrackers from a fourth of July party and the apology note from the first marital spat she had with her husband, the goofy handwriting, the Campbell soup recipes, things that were very much a part of 1949-1951. They become such portals into social, economic and material culture history.

In your book, you describe how scrapbooking has evolved. Preformatted memory books, like baby and wedding books, were more about documenting. And scrapbooking today is more about purchasing materials than using vestigial ones. Why the shift?

It shows that there is an economic incentive. If you see that there is a trend that something is happening you want to jump on the bandwagon and be part of it. My guess is that some very savvy publishers in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s said they were going to make memory books that told you what to remember. That to me is very interesting because it shaped the way we started to value certain memories over others. It was good and bad; they were doing what Facebook does for us now. Facebook will change the way we think about sharing pictures and stories about our mundane lives the same way those publishers made those books and told you to save the fingerprints of your babies.

You’ve been quite vocal and critical about contemporary scrapbooking, and yet you haven’t called it “crapbooking,” as other graphic designers have. Where do you stand?

What I’ve been trying to advocate is that it’s an extremely authentic form of storytelling. You just save something, reflect on it, put it next to something else and suddenly there’s a story instead of the story being sanctioned by pink ribbons and matching paper. I don’t say don’t go to the store and buy pretty stuff. But my fear is that a certain monotony will come out of our reliance on merchandise. How is it possible that all our scrapbooks will be beautiful because they look like Martha Stewart’s, when are lives are all so incredibly different? With so much reliance on the “stuff” a certain authenticity is lost. I kept seeing this expression of “getting it right,” women wanting to “get it right.” Everybody made scrapbooks a hundred years ago, and people didn’t worry about getting it right. They just made things, and they were messy, incomplete and inconsistent. To me, the real therapeutic act is being who you are. You stop and you think what was my day. I planted seeds. I went to the store. Maybe it’s really mundane but that’s who you are, and maybe if you think about it, save it and look at it, you’ll find some truth in that that’s actually very rewarding. It’s a very forgiving canvas, the scrapbook.

As journalists, we’re all wondering whether the print newspaper and magazine will survive the digital age. Do you think the tangible scrapbook will survive in the advent of digital cameras, blogs and Facebook?

I hope they won’t disappear. I personally think there is nothing that replaces the tactile—the way they smell, the way they look, the dried flowers. There’s just something really amazing about seeing a fabric sample from 1921 in a book when you haven’t ever seen a piece of fabric that color before. There’s a certain recognition about yourself and about your world when you see something that no longer exists. When it’s on the screen, it’s a little less of that immersive experience. At the same time, if there is a way to keep scrapbooking relevant, move it forward, make it be a satellite of its former self and move into some new zone and become something else, then that’s a progressive way of thinking about it moving into the next generation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)