The Child Prodigies Who Became 20th-Century Celebrities

Every generation produces kid geniuses, but in the early 1900s, the public was obsessed with them

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Child-Prodigies-Celebrities-631.jpg)

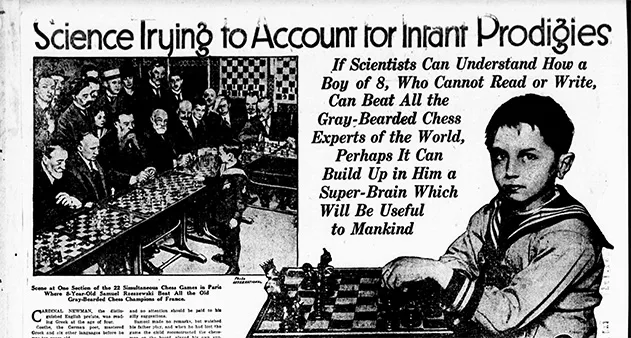

In the first few decades of the 20th century, child prodigies became national celebrities. Much like the movie stars, industrial titans and heavyweight champs of the day, their exploits were glorified and their opinions quoted in newspapers across the United States.

While every generation produces its share of precocious children, no era, before or since, seems to have been so obsessed with them. The recent advent of intelligence testing, which allowed psychologists to gauge mental ability with seemingly scientific precision, is one likely reason. An early intelligence test had been demonstrated at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893—the same exhibition that introduced Americans to such wonders as the Ferris wheel, Cracker Jacks and hula dancing. Then, in 1916, Stanford University psychologist Louis Terman published the Stanford-Binet test, which made the term intelligence quotient, or I.Q., part of the popular vocabulary.

A child’s I.Q. was based on comparing his or her mental age, determined by a standardized series of tests, to his or her chronological age. So, for example, a 6-year-old whose test performance matched that of a typical 6-year-old was said to have an average I.Q., of 100, while a 6-year-old who performed like a 9-year-old was awarded a score of 150. Ironically, Alfred Binet, the Frenchman whose name the test immortalized, had not set out to measure the wattage of the brightest children but to help identify the least intelligent, so they might receive an education that better suited them.

Also contributing to the prodigy craze was a change in the nature of news itself. The early 20th century marked the rise of tabloid newspapers, which put greater emphasis on human interest stories. Few subjects were of more human interest than children.

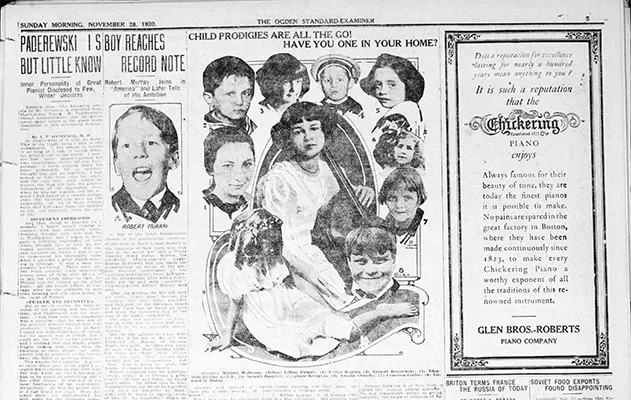

It was the highest I.Q. children and other spectacularly precocious youth who made the best stories, of course. Generally the press covered them with reverence, if not awe. “Infant Prodigies Presage A World Made Richer by A Generation of Marvels,” gushed one New York newspaper in 1922. Others treated them simply as amusing curiosities, suitable for a Ripley’s “Believe It or Not!” cartoon, where, indeed, some of them eventually appeared. Meanwhile, for parents wondering whether they might have one under their own roof, the papers ran helpful stories like “How to Tell If Your Child Is a Genius.”

At roughly the height of the prodigy craze, in 1926, Winifred Sackville Stoner, an author, lecturer, and gifted self-publicist, had the ingenious idea of bringing some of the little geniuses together. The founder of an organization called the League for Fostering Genius and herself the mother of a famous prodigy named Winifred Sackville Stoner, Jr., Stoner wanted to introduce the celebrated children to one another and to connect them with rich patrons who might bankroll their future feats. “Surely there is no better way in which to spend one’s millions,” the New York Times quoted her as saying.

Though the full guest list may be lost in time, the party’s attendees included William James Sidis, a young man in his twenties who had been a freshman at Harvard at age 11, and Elizabeth Benson, a 12-year-old who was about to enter college. Benson would later remember Nathalia Crane, a precocious poet of 12, as being there as well, although if she was, contemporary news accounts seem to have missed her. So what became of these dazzlingly bright prospects of yesteryear? Here, in brief, are the very different tales of Sidis, Benson and Crane, as well as Stoner, Jr.

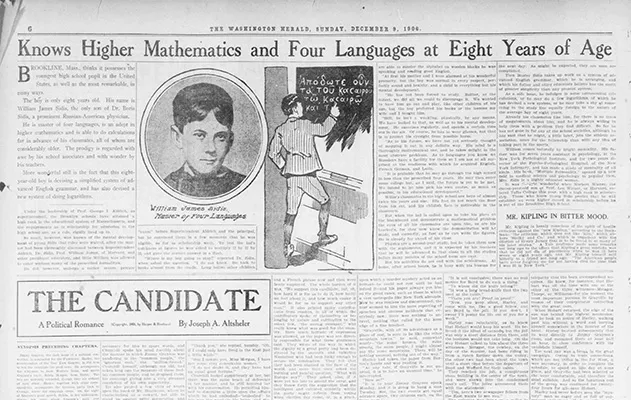

William James Sidis, Boy Wonder

Perhaps the most celebrated prodigy of the early 20th century, William James Sidis would grow up to become the poster child for the perils of early fame.

Born in New York City in 1898, Sidis was the child of Russian immigrant parents, both high achievers themselves. His father was a noted psychologist and protégé of the philosopher-psychologist William James, after whom the boy was named. His mother had earned an M.D. but seems never to have practiced medicine, devoting her time instead to her husband and son.

Spurred on by his parents, in particular his father, who believed that education should begin in the crib, Sidis showed a gift for languages and math at an age when most children are content just to gurgle. According to The Prodigy, a 1986 biography by Amy Wallace, older kids would stop his baby carriage as he was being wheeled through the park to hear him count to 100. At 18 months he was reportedly reading The New York Times, and as a 3-year-old he taught himself Latin.

Sidis made headlines when he started high school at eight and Harvard at 11. His lecture to the Harvard math club on one of his favorite subjects, the fourth dimension , an obscure area of geometry, was widely covered, even if few people seemed to know what he was talking about.

By the time Sidis graduated from college, he’d had his fill of fame and was known to run at the sight of newspaper reporters. He taught briefly, spent some time in law school and flirted with Communism, but his greatest passion seemed to be his collection of streetcar transfers, a subject he wrote a book about using a pseudonym. He would later write other books under other pseudonyms, including a history of Native Americans.

To support himself, Sidis worked at a string of low-level office jobs. When the New Yorker tracked him down for a “Where Are They Now?” article in 1937, it described him as living in a small room in a shabby section of Boston and quoted him as saying that, “The very sight of a mathematical formula makes me physically ill.” Sidis, then 39, sued the magazine for invading his privacy and lost in a landmark case.

Sidis died in 1944 at age 46, apparently of a cerebral hemorrhage. He left behind a pile of manuscripts and at least one big mystery: Was he simply a pathetic recluse who never fulfilled his early promise or a man who succeeded in living life on his own terms, free from the demands of being a prodigy?

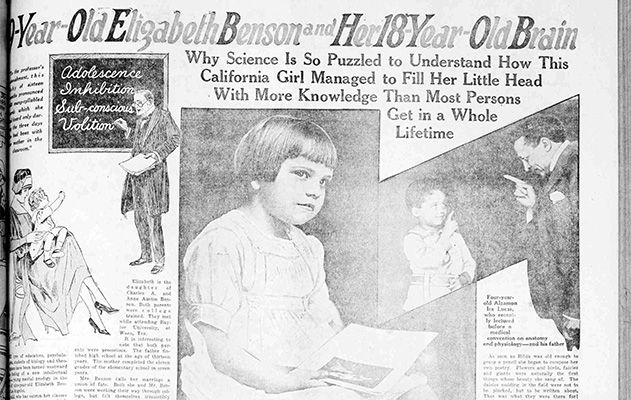

Elizabeth Benson, Test-buster

With an I.Q. of 214 plus, then the highest ever recorded, Elizabeth Benson was a celebrity at the age of eight, though her mother wouldn’t let her read her clippings for fear she’d become conceited. The “plus” meant she had broken the scale, successfully answering every question until her testers ran out of them. There was no telling how high she might have scored.

Benson, born in Waco, Texas in 1913, was raised by her mother, Anne Austin, a journalist who later wrote popular mystery novels with titles like Murder at Bridge and The Avenging Parrot. As her mother’s career progressed, the two moved around, with stops in Iowa, California and Missouri, as well as several Texas cities. By the time young Elizabeth graduated from high school, at age 12, she had attended a dozen different schools.

Though she seems to have excelled at just about everything, Benson’s interests were mainly literary. She taught herself to spell by age 3 and was soon consuming a dozen library books a week. At 13, during her sophomore year at Barnard College in New York City, she published one of her own, The Younger Generation, offering her wry take on the antics of Roaring Twenties youth. In his introduction to the book, Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield marveled not only at the young teenager’s writing skill but also her athletic ability. “A learned physician has hinted to me that the hair-trigger balance between her physical and intellectual natures is probably due to the perfect functioning of her endocrine glands,” he explained, or at least attempted to.

After graduating from college in 1930 Benson dropped from public view. She reemerged four years later, when a reporter found her living in a small apartment in New York, married, and working as a cashier. Time magazine then picked up the story, treating her to further national acclaim, not for being a genius but for turning out so normal.

In the late ’30s, however, Benson’s life appeared to take a radical turn, literally: She returned to her native Texas as Communist organizer. When her group tried to hold a rally at San Antonio’s municipal auditorium, the result was a riot by a reported 5,000 anti-Communist Texans.

Benson next headed to Los Angeles, where she continued her organizing work in the movie industry. But by the late 1950s, she’d grown disenchanted with Communism, finally breaking with the party in 1968, according to her son, Morgan Spector. She then earned a law degree, taught real property courses and practiced as a labor lawyer. She died in 1994, at age 80, an event that seems to have gone unnoticed by the media that once followed her every move.

Nathalia Crane, Precocious Poet

Nicknamed the “Baby Browning of Brooklyn,” Nathalia Crane, born in 1913, was a nationally known poet by age 10, acclaimed for such works as “Romance,” later retitled “The Janitor’s Boy,” a girlish fantasy about escaping to a desert isle with the red-haired title character from her apartment house. Crane, her poems, and even the ordinary, real-life boy who inspired her poetic effusions were celebrated in newspapers from coast to coast.

Nunnally Johnson, later to make his name as a screenwriter and director, observed the spectacle as a young reporter. “Camera men and moving picture photographers shuffled through the apartment-house court to Nathalia’s door,” he wrote. “She was asked imbecile questions: her opinions on love, on bobbed hair, on what she wanted to be when she grew up.”

It wasn’t long, however, before Crane’s unusual way with words had raised suspicions that she might be a fraud. Conspiracy theorists tried to attribute her poems to everyone from Edna St. Vincent Millay to Crane’s own father, a newspaperman who had demonstrated no particular gift for poetry. Eventually the doubts subsided, and by the end of her teens, Crane’s credits included at least six books of poetry and two novels.

Crane would publish little from the 1930s until her death in 1998. Instead, she went to college and took a series of teaching jobs, ending her career at San Diego State University.

Aside from a brief brush with controversy as a supporter of the Irish Republican Army, Crane rarely stood out in her later years, according to Kathie Pitman, who is working on her biography. “She seems to have been a very quiet, very diffident person, certainly not larger than life,” Pitman says. “It may be that she just tired of all the emphasis that was put on her as a prodigy.”

Though Crane’s work is largely forgotten, it enjoyed a recent revival when Natalie Merchant set “The Janitor’s Boy” to music for her 2010 album, Leave Your Sleep.

Winifred Sackville Stoner, Jr., the Wonder Girl

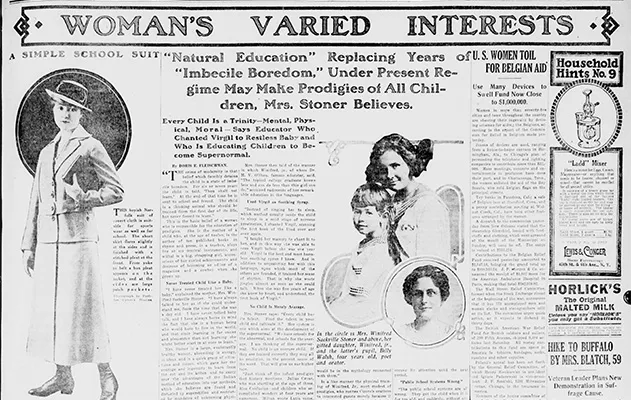

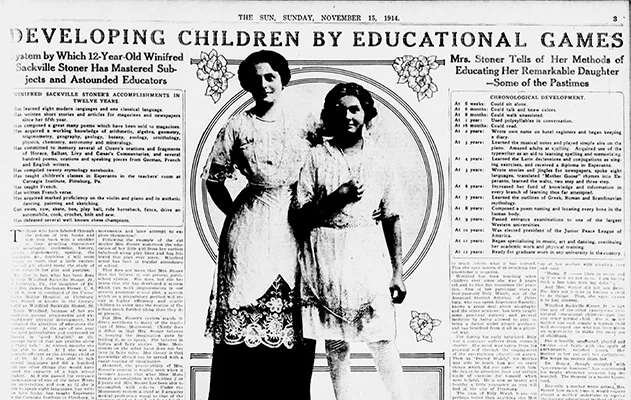

The curiously named Winfred Sackville Stoner, Jr., born in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1902, was the daughter of Winifred Sackville Stoner, a self-styled education expert who read her baby classic poetry and decorated her nursery with copies of great paintings and sculptures. Her father was a surgeon with the U.S. Public Health Service, whose frequent reassignments kept the family on the move. By the age of 10, his daughter had lived in

Evansville, Indiana, Palo Alto, California, and Pittsburgh—and become a local legend in each of them.

Young Winifred supposedly translated Mother Goose into Esperanto at five, passed the entrance exam for Stanford at nine, and spoke eight languages by 12, when she wasn’t playing the violin, piano, guitar or mandolin. Remember the famous line “In fourteen hundred ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue”? She wrote it. No wonder the newspapers gave her nicknames like the Wonder Girl.

As Winifred, Jr., gained a reputation as a prodigy, her mother became equally well-known as the brains behind one. Mother Stoner, as she was often referred to, published several books explaining how she had reared her amazing daughter and lectured widely on her theories, which she called “natural education.” Like William Sidis’s father, Boris, whom she quoted admiringly, she believed that a child’s education couldn’t begin too early. Indeed, she did Sidis one better and didn’t even wait for her baby to be born to start classes. “Through prenatal influence,” she wrote somewhat cryptically, “I did all in my power to make my little girl love great literature in many languages.”

By the late 1920s, however, the younger Stoner was getting more attention for her chaotic personal life than her artistic achievements. Still a teenager, she had married a phony French count who turned out to be a con man. After he faked his own death, she remarried, only to discover that she now had two husbands. She won an annulment from the “count,” but divorced her second husband anyway, saying he had insulted her coffee. Further husbands and other embarrassments would follow.

Stoner died in 1983, having long since renounced any claim to being a role model. In a 1930 article she described her youth as being “puffed to the skies and then pitch-forked.” Her closing words: “Take my advice, dear mothers; spare your children from so-called fame, which easily turns to shame, and be happy if you have a healthy, happy, contented boy or girl.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)