The Cowboy in Country Music

In his new book, music historian Don Cusic recounts the enduring icons of western music and their indelible mark on pop culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Country-Music-Cowboys-Gene-Autry-631.jpg)

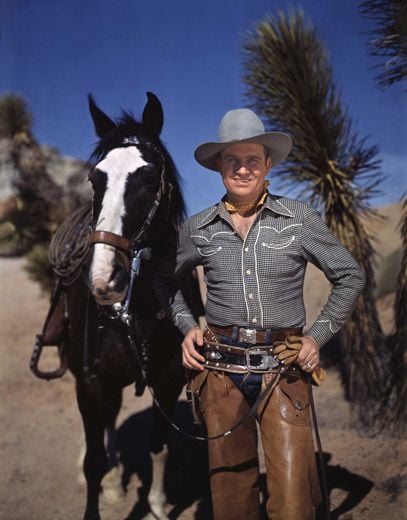

Don Cusic’s new book, The Cowboy in Country Music: An Historical Survey with Artist Profiles (McFarland), explores how the cowboy became an American pop culture icon and the face of country music. Cusic is a music historian and professor of music business at Belmont University in Nashville. His book profiles artists who have embraced and promoted ideas about cowboys and the American West, including performers of western music, which he identifies as an offshoot of country music. Most of the profiles – from Gene Autry to George Strait – were first published in the magazine The Western Way, for which Cusic is editor.

I talked with Cusic about how performers have fashioned their cowboy look and why Americans are still drawn to this image.

From the late 1940s through the 1960s there was a musical genre called “country and western,” but today there are two different camps – country music and western music. This book focuses more on the later. How do you define western music? What is its relationship to country music?

Musically [the two] are basically the same thing. The difference in western is in the lyrics. It deals with the West – the beauty of the West, western stories. The western genre has pretty much disappeared. The country music cowboy is a guy who drives a pick-up truck – he doesn’t have a horse, there’s no cattle. In movies like Urban Cowboy, [he] works not on a ranch but in the oil industry. At the same time there’s this thriving subgenre of people who work on ranches or own ranches and are doing western things and [playing] western music – reviving it. Country’s not loyal to a sound – it’s loyal to the market. Western music is loyal to a sound and an image and a lifestyle. But less than 2 percent [of the U.S. population] lives on farms or ranches today.

As you point out, there’s a difference between a “real” working cowboy and the romantic, heroic figure that emerged to represent country music. When and how did the cowboy become a big player in American popular culture?

Back with Buffalo Bill and his Wild West Shows. He kind of glamourized the West, and so did the dime novels. Buffalo Bill had a guy called “King of the Cowboys” – he was a romantic hero. Then when the early movies came, westerns were popular. In music, the [cowboy] comes along a little later in the 1930s with Sons of the Pioneers, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers in the singing cowboy movies.

Who were the most popular early cowboy heroes of film and radio?

Well, the first big western hit [song] was “When the Work’s All Done This Fall” by a guy named Carl Sprague [recorded 1925]. In the movies, it was William S. Hart and then Tom Mix. Tom Mix dressed like somebody who didn’t work with cattle; he brought the glamour in. Coming out of the early 1930s, [after] Prohibition, gangsters and the “flaming youth” movies, the cowboy was a good, clean alternative. And Gene Autry was the first singing cowboy star.

Why do you think Autry was so popular?

He was like a breath of fresh air. The movie people didn’t like him – they thought he was too feminine, not masculine enough to be a cowboy hero. But he had an appealing voice, he had that presence, he kind of had that “next-door” look, and he was a great singer. One of the things he did in his movies was put the old West in the contemporary West. People rode horses, but they also drove pick-up trucks. They chased bad guys, but they also had a telephone and a phonograph.

What about cowgirls? What role did musicians such as Dale Evans and the Girls of the Golden West play in the evolution of cowboy music and culture?

Patsy Montana had that first big hit, “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart,” but women were relegated to pretty much a subservient role – the schoolmarm, the innocent spoiled brat, those kind of roles. Dale Evans changed that a bit, but not until she got into television when [she and Roy Rogers] were openly married and she was running a café [on “The Roy Rogers Show”].

You say the singing cowboy films of the 1930s and ’40s brought country music into the realm of pop music and that the cowboy replaced the hillbilly as country’s mascot of sorts. The hillbilly image was created in part to help sell the records or promote “barn dance” radio shows. Were record companies and advertisers similarly involved in creating the cowboy image?

The cowboy was a positive image, as opposed to the hillbilly, which was considered a negative image. The cowboy, I think, was just more appealing. That’s something you could want to be – you didn’t want to be a hillbilly but you did want to be a cowboy.

Why are cowboys and westerns still attractive to people?

The self-image of rugged individualism. That whole idea that we did it all ourselves. The cowboy represents that better than any other figure. He’s a lone guy on a horse, and it doesn’t matter how many people are in town that want to beat him up – he beats them up. It fits how we see capitalism.

Talk about the evolution of what is now called western music. What role did the cowboy and the West play in country music after the 1950s and why was there a western music revival in the 1970s?

What we see after World War II is farm guys moving to town, where they want to wear a sports coat and have a cocktail – they want to be accepted into the middle class. The “Nashville sound” put a tuxedo on the music – it started with the Nudie suits and then the tuxedos. Then in the 1970s, all of the sudden, when the [United States’] 200th anniversary hit, we jumped back into cowboy. I think a lot of it had to do with demographics. The baby boomers who grew up on the cowboy shows lost all that in the ’60s – we were all on the street and smoking funny stuff. Then by the ’70s the cowboy came back because [people wanted to] capture that childhood again.

Who are some of the musicians that represent that revival era?

The biggest were Waylon and Willie, with the “outlaw” movement. It’s funny, they were cowboys, but they wore black hats instead of white hats. In terms of western culture, Riders in the Sky and Michael Martin Murphy were leaders. But a lot of country acts were dressing as cowboys and singing about the West or western themes. If you listen to the song “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” the cowboy loves little puppies and prostitutes – sort of like Keith Richards in a cowboy hat.

So with the outlaw country movement, the cowboy isn’t so clean and pure anymore.

Sex, drugs and rock and roll hit country in the ’70s. That’s what the cowboy was in country music [then] – sort of the hippie with the cowboy hat. Independent, individualist. That ’60s figure, the liberated person, had a cowboy hat and cowboy boots on by the mid-’70s.

In the book, you profile early artists such as Patsy Montana, Tex Ritter and Bob Wills but also more recent acts, including Asleep and the Wheel and George Strait. You say Strait is the most western of contemporary, mainstream country musicians. Why?

He actually owns a ranch and works on it. He does rodeos with roping. He sings some cowboy songs, and he certainly dresses as a cowboy – he’s the real deal. Strait is doing today what the old singing cowboys – the Autrys and the Rogers – did back then.

Do you notice other artists – including those outside mainstream country – embracing the cowboy image today?

Some of the alt-country artists do, but it’s a campy thing. Not like “I’m a real cowboy and I know how to ride a horse.” A lot of music is attitude. Cowboy is an attitude of “We’re basic, we’re down to earth, we’ve got values rooted in the land.”

What about younger musicians – are they interested in cowboy culture?

From what I’ve seen they may wear cowboy hats, but increasingly country performers are much more urban. I think they embrace the clothes more than they embrace the full culture. I mean, I grew up on a farm – you don’t want to take care of cattle.