The Curious Case of a Gigantic Sham Clam

Geoducks are a staple of Chinese New Year. But did one grow to the size of a wheelbarrow?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120123120029geoduckt.jpg)

The necks of geoduck clams can grow up to two and a half feet long. Pick one up and it’s hard not to conjure up a tender part of the human anatomy. As Mark Kurlansky writes, the “long phallic neck squirts water and then sadly falls flaccid.” They’re also a staple of the Chinese New Year, served as xiàng bá bàng (“elephant trunk clam”). Since geoducks (pronounced goo’e duk and originally meaning “dig deep”) live for over 150 years, they can become really meaty—up to 14 pounds.

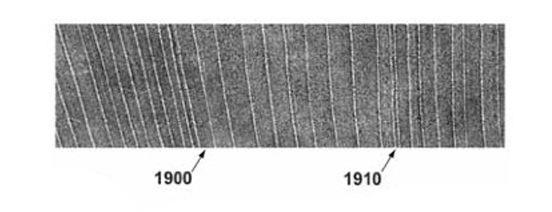

Just how big they get came into question in 1981, when J. D. Barnes published a review of the textbook Skeletal Growth of Aquatic Organisms in the journal Science. The book explains, among other things, how mollusk shells contain biochronologies of geophysical and paleoecological information, like the rings of a tree—albeit in an organism pulled by the tides and the moon. “They are now seen as virtual transcripts of what happened in their environment during their deposition,” Barnes wrote. “Of course, the transcripts are in code, and the deciphering of the codes has only just begun.”

Scanning electron micrograph of the ring structure from a 163-year-old geoduck/Are Strom/American Geophysical Union

Clamshells essentially act as kind of natural instrumentation for recording environmental conditions in their annual growth rings—from changes in lunar magnetism to the detonation of atomic bombs. First identified as climate proxies in 1992, the bands on a geoduck shell also provide a century-old record of fluctuations in the ocean’s surface temperature. Fascinating and important stuff, indeed.

What’s odd is that the 1981 book review included an intriguing photograph, found in the book and attributed to an unknown photographer, of a boy hunched over a wheelbarrow. The photo depicts a massive geoduck clam with its distinctive growth bands. The only problem: It’s a jackalope of the sea—except that rather than a mythical creature invented in 1934 by a skilled Wyoming taxidermist, the oversized geoduck is an unnatural exaggeration of an actual organism.

“The light on the clam comes from the right side and above, while that on the boy’s face and hand is clearly from the left,” biologist Stuart Landry wrote Science. “A clam the size shown would exceed the size limits for a sessile filter feeder.” Another reader reported that, indeed, he had seen the very photo in a gift shop, right alongside the postcard of a jackalope. (One collector identifies the photographer as Johnston #1768, and, indeed, there are other postcards involving gigantic clam wrestling.)

Perhaps the over-sized geoduck provides a lighthearted invention, exhibiting regional pride, like other tall-tale postcards depicting corn that fills an entire railcar or squash the size of trucks. The image may also hint at a more troubling issue—the indelible changes in the environment that are being inscribed onto clam shells. Certainly, something to chew on this year.

Want to learn how to cook geoduck? Check out the video below: