The Daring Escape From the Eastern State Penitentiary

Archeologists had to look deep into the catacombs of the prison to find the tunnels dug by criminals in 1945

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eastern-penitentary-escape-tunnel-470.jpg)

Eastern State Penitentiary opened its gates in 1829. It was devised by The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, an organization of powerful Philadelphia residents that counted Benjamin Franklin among its members and whose ambition was to “build a true penitentiary, a prison designed to create genuine regret and penitence in the criminal’s heart.” With its hub-and-spoke design of long blocks containing individual prison cells, ESP could be considered the first modern prison. There are many, many stories told about the prisoners that have been incarcerated here over its nearly 150 years of operation–some inspiring, some horrible, some about Al Capone–but none of them have captivated the public more than the 1945 “Willie Sutton” tunnel escape.

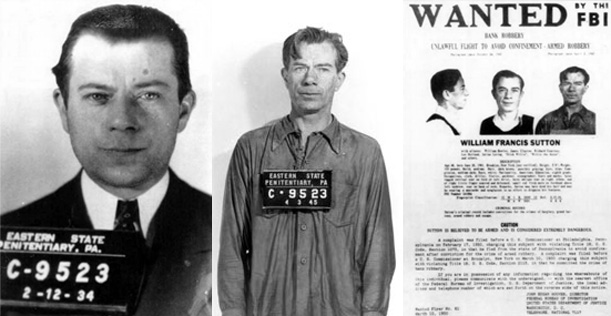

Photo of Willie Sutton’s in 1934; a photo taken mere minutes after his escape in 1945; Sutton’s post-escape mug shot; the wanted poster issued after Sutton’s escape from Holmesburg. At the time he was one of the FBI’s ten most wanted fugitives (image: Eastern State Penitentiary)

The most famous escape in the history of Eastern State Penitentiary was the work of 12 men – they were like the Dirty Dozen, but less well adjusted. The most infamous among them was Willie Sutton aka “Slick Willie” aka Willie “The Actor” aka “The Gentleman Bandit” aka “The Babe Ruth of bank robbers,” who was sentenced to Eastern State Penitentiary in 1934 for the brazen machine gun robbery of the Corn Exchange Bank in Philadelphia. Those nicknames alone tell you everything you need to know about Willie Sutton. He was, by all accounts (especially his own), exactly what you want a old-timey bank robber to be: charming, devious, a master of disguise, and of course, an accomplished escape artist, who in 11 years at ESP, made at least five escape attempts. Sutton’s outspoken nature and braggadocio landed him a few stories in Life magazine and even a book deal. In his 1953 autobiography Where the Money Was, Sutton takes full credit as the mastermind behind the tunnel operation.

Clarence Klinedinst in the center (image: Temple University Archives via Eastern State Penitentiary)

Though the personable Sutton may have been critical in managing the mercurial tempers of his fellow escapees, the truth is that the escape was planned and largely executed by Clarence “Kliney” Klinedinst, a plasterer, stone mason, burglar, and forger who looked a little like a young Frank Sinatra and had a reputation as a first-rate prison scavenger. “If you gave Kliney two weeks, he could get you Ava Gardner,” said Sutton. And If you give Kliney a year, he could get you out of prison.

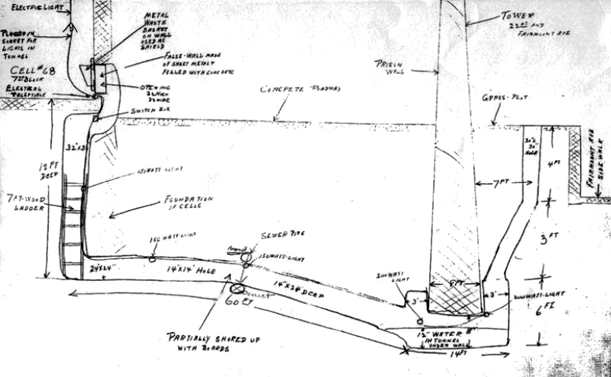

Working in two-man teams of 30 minute shifts, the tunnel crew, using spoons and flattened cans as shovels and picks, slowly dug a 31-inch opening through the wall of cell 68, then dug twelve feet straight down into the ground, and another 100 feet out beyond the walls of the prison. They removed dirt by concealing it in their pockets and scattering it in the yard a la The Great Escape. Also like The Great Escape, the ESP tunnel was shored up with scaffolding, illuminated, and even ventilated. At about the halfway point, it linked up with the prison’s brick sewer system and the crew created an operable connection between the two pipelines to deposit their waste while ensuring that noxious fumes were kept out of the tunnel. It was an impressive work of subversive, subterranean engineering, the likes of which can only emerge from desperation. As a testament to either clever design or the ineptitude of the guards, the tunnel escaped inspection several times thanks to a false panel Kliney treated to match the plaster walls of the cell and concealed by a metal waste basket.

After months of painfully slow labor, the tunnel was ready. On the morning (yes, the morning) of April 3, 1945, the dirtier dozen made their escape, sneaking off to cell 68 on their way to breakfast.

Two of the escapees, including Sutton (at left), are returned to Eastern after mere minutes of freedom. (image: Eastern State Penitentiary)

Like most designers, Kliney and co. found that the work far outweighed the reward. After all that designing, carving, digging, and building, Kliney made it a whole three hours before getting caught. But that was better than Sutton, who was free for only about three minutes. By the end of the day, half the escapees were returned to prison while the rest were caught within a couple months. Sutton recalls the escape attempt in Where the Money Was:

“One by one the men lowered themselves to the tunnel, and on hands and knees crept the hundred and twenty feet to its end. The remaining two feet of earth were scraped away and men rumbled from the hole to scurry in all directions. I leaped from the hole, began to run, and came face to face with two policemen. They stood for a moment, paralyzed with amazement. I was soaking wet and my face was covered with mud.

“Put up your hands or I’ll shoot.” One of them recovered more quickly than the other.

“Go ahead, shoot,” I snarled at them, and at that moment I honestly hoped he would. Then I wheeled and began to run. He emptied his gun at me, but I wasn’t hit….None of the bullets hit me, but they did make me swerve, and in swerving I tripped, fell, and they had me.”

The first few escapees to be captured, Sutton among them, were put in the Klondikes – illegal, completely dark, solitary confinement cells secretly built by guards in the mechanical space below one of the cell blocks. These spaces are miserable, tiny holes that aren’t big enough to stand up or wide enough to lie down. Sutton was eventually transferred to the “escape proof” Holmesburg Prison, from which he promptly escaped and managed to avoid the law for six years. Police eventually caught up with him in Brooklyn after a witness saw him on the subway and recognized his mug from the wanted poster.

The map of the 1945 tunnel made by guard Cecil Ingling. In his larger-than-life account of the escape, Sutton claimed the tunnel went 30-feet down. “I knew that the prison wall itself extended 25 feet beneath the surface of the ground and that it was fourteen feet thick at the base.” Clearly, that wasn’t the case. (image: Eastern State Penitentiary)

As for the tunnel, after it was analyzed and mapped, guards filled it with ash and covered it with cement. Though it may have been erased from the prison, its legend likely inspired inmates until Eastern State Penitentiary was closed in 1971. And despite the failure of the escapees, the tunnel has continued to intrigue the public.

Archaeologists use ground-penetrating radar and an auger to detect the remains of the 1945 tunnel on the occasion of its 60th anniversary. (images: Digging in the City of Brotherly Love)

The location of the tunnel was lost until 2005, when the Eastern State Penitentiary, now a non-profit dedicated to preserving the landmarked prison, completed an archaeological survey to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the escape. To find the tunnel, the prison escape preservationists created a search grid over the prison grounds near the entrance, the location of which was known from old photos. Using ground penetrating radar, the team was able to create vertical sections though the site in increments corresponding to the suspected width of the tunnel. After a couple failed attempts, the archaeologists detected a section of the tunnel that hadn’t collapsed and hadn’t been filled-in by the guards. The following year, a robotic rover was sent through the tunnels, documenting its scaffolding and lighting systems. While no major discoveries were made, curiosity was sated and the public’s imagination was newly ignited by stories of the prison and its inmates.

There’s something undeniably romantic about prison escapes – perhaps due to the prevalence of films where the escapee is the hero and/or the pure ingenuity involved in a prison escape. The best escape films –A Man Escaped, La Grande Illusion, Escape from Alcatraz, The Great Escape, to name just a few–show us every step of the elaborate plan as the rag tag team of diggers, scavengers, and ersatz engineers steal, forge, design, and dig their way to freedom. Without fail, the David vs. Goliath narrative has us rooting for the underdog every step of the way, even when the David is a bank robber.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)