The Debate Continues Over How to Rebuild New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward

Five years in, the merits of Make It Right’s housing project are under new scrutiny

![]()

It’s been five years since the Make It Right organization broke ground on their first house in the Lower 9th Ward neighborhood in New Orleans, an area that was completely devastated by Hurricane Katrina. The non-profit was formed in 2007 with the optimistic and ambitious plan to build 150 sustainable homes for returning residents who were struggling to rebuild. From the very beginning it was a high-profile project, partially because of the 21 renown architects commissioned to design new homes and duplexes for the area, but mostly due to the fact that it was founded by actor and architecture enthusiast Brad Pitt, whose celebrity gave the project an early boost and briefly made it a cause cêlèbre for many wealthy donors. This week, The New Republic ran a disparaging piece questioning the progress that Make It Right has made over the last five years, and MIR Executive Director Tom Darden responded with his own strongly worded rebuttal, calling The New Republic piece by Lydia DePillis a “flawed and inaccurate account” of their work. Taken together, the two articles provide some compelling insight into the nature of the project and, more broadly speaking, the benefits and detriments of large-scale building projects in disaster-stricken cities.

I should probably say up front that I lived in New Orleans for more than six years and left the city in the wake of Katrina. After leaving, I visited New Orleans frequently and would occasionally document the progress of the Make It Right development on my personal blog. The reconstruction of the Lower 9th Ward is a complex issue with both emotional and political ramifications. There is no right answer to disaster recovery and there probably never will be. That’s what makes it such a fascinating and incredibly difficult problem. Make It Right believed that good design is the solution.

But of course, good design is expensive. One of the biggest complaints levied against Make it Right by DePillis is the cost of their houses:

Make It Right has managed to build about 90 homes, at a cost of nearly $45 million, in this largely barren moonscape—viewed from the Claiborne Avenue Bridge, which connects the ward to the center city, they spread out like a field of pastel-colored UFOs….Construction on the cutting-edge designs has run into more than its share of complications, like mold plaguing walls built with untested material, and averaged upwards of $400,000 per house. Although costs have come down, Make It Right is struggling to finance the rest of the 150 homes it promised, using revenue from other projects in Newark and Kansas City to supplement its dwindling pot of Hollywood cash.

The article argues that the same amount of money could have potentially been used to accomplish much more. It’s a valid point that many people agree with, but TNR played it a little fast and loose with their numbers. Make It Right has actually spent $24 million on the construction of 90 homes. Still a significant amount, and Darden admits that yes, more conventional homes could be built more cheaply and in greater numbers. But that was never the point of Make It Right. Not exactly, anyway. The organization was formed to build high-quality homes for those that needed them the most. Darden writes:

While the academic debate about the fate of the Lower 9th Ward raged, families were already returning to the neighborhood, living in toxic FEMA trailers and planning to rebuild. These homeowners had decided to come home, but lacked the resources to rebuild in a way that would be safe and sustainable. Make It Right decided not to try to build as many houses as possible, but to design and build the best houses possible for this community.

For Make It Right, “the best” means that all houses meet stringent design guidelines that require them to meet the highest sustainability standard, LEED Platinum, incorporate new building technologies, and work with the latest construction methods and materials. Additionally, every home is structurally engineered to withstand 130 mph winds and five-foot flood surges.

Those designs are a mixed bag, and in some cases the final built project bears little resemblance to the original design. This is due to the fact that, as I understand it, the design architects relinquish control of their projects after handing over construction documents to Make it Right’s team of architects and builders. Ostensibly, this is to help keep costs down and strengthen the vernacular elements of each building to create something that feels like a true neighborhood despite the fact that it was born from disparate architectural visions. One of the most jarring examples of this is the minimalist home designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban:

left: rendering of Shigeru Ban’s Make It Right house. right: the final built project in 2009 (images: Make It Right; authors photo)

From rendering to reality, something got lost in translation. The strong horizontals of Ban’s design have been lost to extraneous moldings, some profound design changes, and a less than flattering paint job. Though these may seem like small concessions, the cumulative result has destroyed the craft and elegance that was a critical element of the original design. To be fair though, these changes may have been the result of conversations between MIR and the homeowner. Collaboration is a key part of the MIR process. But if such drastic changes were necessary, I can’t help but think that Ban’s design shouldn’t have been considered in the first place. There are a few other questionable designs by architects that just don’t seem to “get” building in New Orleans, and during my last visit to Lower 9th Ward back in 2010, I couldn’t help but think that it felt more like an exhibition of experimental housing than a neighborhood. Perhaps that will change with time, natural growth, and much-needed commercial development.

To be sure though, there are also some terrific designs. While it’s exciting and press-friendly to have projects from high profile international architects like Ban, Frank Gehry, Morphosis, and David Adjaye, I think the most successful Make It Right homes have come from local architects like Waggoner & Ball and Bild design, who are familiar with the city’s traditional architecture have have created some of the most innovative houses in New Orleans by analyzing and reinterpreting classic local building types like the “shotgun house” and the “camelback.” For these firms, it’s not about always about imitating how the traditional buildings looked, but how they performed.

Design aside, perhaps The New Republic’s ire is misdirected. I can’t believe that the people behind Make It Right have anything but the best intentions for the city and are doing the best they can to fulfill their mission. However, some people have argued –and continue to argue– that they should never have been allowed to begin. The 9th Ward is one of the more remote parts of the city and due to its near total devastation, there was some speculation that the neighborhood might be abandoned completely and allowed to transform back into a natural flood plain. There was even talk that the entire city might shrink – a not implausible idea. After all, Detroit recently unveiled a 50-year plan, dubbed “Detroit Future City,” to do just that:

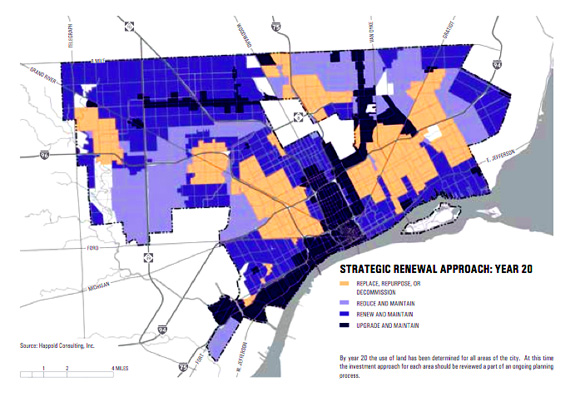

A planning map from the Detroit Future City plan. The areas in tan will be decommissioned or repurposed (image: Detroit Future City)

The Motor City hopes to manage its shrinking population with large-scale “deconstruction” to clean up blighted and sparsely occupied neighborhoods that pose a threat to public safety and an unnecessary strain on civic infrastructure. These decommissioned blocks will be replaced with parks, “ecological landscapes,” and even urban farms. The idea is that the city’s limited resources could be more efficiently employed in dense areas. It’s like a utopian plan mixed with the plot of RoboCop.

However, the City of New Orleans, for reasons that were surely both emotional and political, elected not to shrink their footprint. The strain on resources and infrastructure that may have resulted from this decision is one of the problems highlighted by The New Republic piece. This has been a constant debate since the rebuilding began. Why divert valuable resources to remote areas instead of relocating those residents to denser areas that are better served? It’s a good question. The city has only recently agreed to invest in the civic infrastructure of the Lower 9th Ward – to the tune of $110 million. This is a welcome relief for some of the city’s residents and for others a waste of funds that comes at the expense of more central neighborhoods. For Make It Right, it’s a sign that the city is finally taking the initiative to invest in more innovative infrastructure. Darden notes that “The new streets are made in part of pervious concrete that reduces runoff by absorbing water,” adding that “The city should be applauded for developing some of the most innovative infrastructure in the country, not chastised for it.” It’s interesting to think that if such innovations were to continue in the Lower 9th Ward, the neighborhood could become a sort of urban laboratory where new sustainable initiatives and materials can be tested –safely, of course– before being used in denser areas throughout the city.

The articles written by The New Republic and Make It Right offer many other salient points and counterpoints and I recommend reading them both for a comprehensive view on the issue. They make for a compelling read and include some touching anecdotes from neighborhood residents. Reconstruction at this scale is an urban issue that Make It Right started addressing with architecture.But architecture can only do so much. There are obviously larger social and political issues that are still need to be figured out. And then of course, there are events that can’t be predicted, like how the remarkable shifting demographics of Post-Katrina New Orleans will change the city. At first, Make It Right was an optimistic, symbolic kick-off to reconstruction. Five years later it’s a become a case study and a contentious point of discussion and debate. But there’s a lot of value to that as well. As I said in the introduction, there is no right answer. But that’s exactly why we need to keep talking.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)