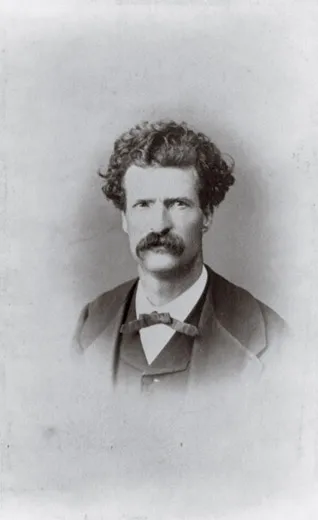

The Decades-Long Comeback of Mark Twain’s Favorite Food

When America’s favorite storyteller lived in San Francisco, nothing struck his fancy like a heaping plate of this Pacific Northwest delicacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Oysters-half-shell-631.jpg)

To Mark Twain, San Francisco was coffee with fresh cream at the Ocean House, a hotel and restaurant overlooking the Pacific. He also had a decided fondness for steamed mussels and champagne. But most of all, San Francisco was oysters—oysters by the bushel at the Occidental Hotel, where the day might begin with salmon and fried oysters and reach its culinary climax at 9 p.m., when, Twain wrote in 1864, he felt compelled “to move upon the supper works and destroy oysters done up in all kinds of seductive styles” until midnight, lest he offend the landlord. Every indication is that his relationship with the landlord was excellent.

Having abandoned Mississippi riverboats in 1861 for fear of being drafted into the Union or Confederate army, Twain had lit out for the West, where he mined silver and crushed quartz in Washoe (in present-day Nevada), and began working as a reporter for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. In 1864, the 29-year-old writer on the verge of fame arrived in San Francisco, a city he called “the most cordial and sociable in the Union,” and took lodgings at the Occidental, where he would live for several month-long stints (likely as much as he could afford) during the next two years. The hotel’s cuisine was a great attraction, and he soon reported that “to a Christian who has toiled months and months in Washoe, whose soul is caked with a cement of alkali dust... [whose] contrite heart finds joy and peace only in Limburger cheese and lager beer—unto such a Christian, verily the Occidental Hotel is Heaven on the half shell.”

Twain’s views on such matters are worth taking seriously; he was a man who knew and loved American food. Several years ago, I set out in quest of his favorite dishes for a book, Twain’s Feast: Searching for America’s Lost Foods in the Footsteps of Samuel Clemens. I had been inspired by a kind of fantasy menu that the great author jotted down in 1897 toward the end of a long European tour, when he was likely feeling homesick, if not hungry. Twain listed, among other things, Missouri partridge, Connecticut shad, Baltimore canvasback duck, fresh butter beans, Southern-style light bread and ash-roasted potatoes. It occurred to me that many of the American foods Twain loved—such as Lake Tahoe Lahontan cutthroat trout and Illinois prairie hens—were long gone, and that their stories were the story of a vanishing landscape, the rushing waters and vast grasslands of his youth obliterated by an onslaught of dams and plows. But what about the oysters he so enjoyed in San Francisco?

Not everyone would have considered the oysters at the Occidental to be a celestial dish. Like all fresh oysters in San Francisco at the time, the Occidental’s were Olympias, the true West Coast natives. Eastern oysters, whether briny Long Island or sweet Texas varieties, belong to a single species (Crassostrea virginica) and tend to be large and plump. By comparison, Olympias (Ostrea conchaphila) are small and their flesh maroon or even purple, imparting a distinctive metallic or coppery note on the palate. Many Easterners were aghast. “Could we but once again sit down to a fine dish of fresh, fat ‘Shrewsbury’ oysters, ‘blue pointers,’ ‘Mill pond,’ ‘Barrataria,’ or ‘Cat Islanders,’” moaned an anonymous journalist, “we should be willing to repent all of our sins.”

Still, other newcomers to the city, including Twain—straight from the Nevada desert with its pickled oysters and an appalling coffee substitute he dubbed “Slumgullion”—developed a taste for the tiny, coppery Olympias. The Oly, as it was called, was the classic gold rush oyster, a staple of celebrations and everyday meals in San Francisco restaurants and oyster saloons. Olys appeared in oyster soup and stew, stuffed into wild poultry and, of course, raw. Perhaps the most distinctive local dish was a “Hangtown fry” of oysters, bacon and eggs.

My search for Olys leads to the venerable Swan Oyster Depot, which moved to its current Polk Street location only six years after Twain’s favorite hotel, the Occidental, collapsed into rubble in the great earthquake of 1906. On a wall inside Swan’s, among photographs and sketches of what appear to be every fish in the sea, hangs a framed 19th-century advertisement, darkened and faded nearly to illegibility: “Oh Friend Get Yours/We Serve Them/Olympia Oysters.”

Actually, Olys are quite rare these days in San Francisco, even at Swan’s. As co-owner Tom Sancimino explains, the oysters are both small and extremely slow growing, making them relatively unprofitable to farm. He sometimes orders them special; he did so recently for a regular customer’s 90th birthday. “We have a real old-time customer base,” he says. “Our customers know what Olys are.”

In Twain’s day, some Olys were harvested in San Francisco Bay. But even then, before silt from hydraulic gold mining in the Sierras sluiced down into the bay to bury and destroy the vast majority of wild oyster beds, most Olys came from the far more productive tidelands of Shoalwater Bay, now known as Willapa Bay, in southern Washington State. Today, Swan’s—or any San Francisco oyster bar wanting to serve the kind of oysters prized by Twain—must look farther north still, to the coves and inlets of Puget Sound.

Even at Taylor Shellfish, a family business in Shelton, Washington, founded during the Olys’ 19th-century heyday, there isn’t a huge market for the diminutive native oysters. At the company’s processing center, countless bins of mussels, clams and other oyster varieties—Totten Inlet Virginicas, Kumamotos, Shigokus, Pacifics—are cleaned, sorted and shucked. Toward the rear of a cavernous room, just a few black-mesh bags of Olys await culling. Once the only product harvested by Taylor, the Oly now approaches a labor of love, raised on perhaps five of Taylor’s 9,000 acres of Puget Sound tidal beds.

Olys require three or four years to reach harvestable size, even under ideal conditions engineered for farmed oysters. In the Taylor hatchery, Oly larvae swim in clean water pumped from a nearby inlet, feeding on algae grown in cylindrical tanks. After a period of rapid growth in a FLUPSY (Floating Upweller System), where giant aluminum paddles provide a constant stream of oxygen and nutrients, the oysters are placed in polyethylene bags to reach maturity in Totten Inlet, situated at the confluence of clean open water and a nutrient-rich salmon run.

All this sophisticated equipment, of course, is relatively new. From the late 1800s to the mid-20th century or so, oyster farmers used simpler technology; they built low wooden dikes in the flats to trap a few inches of water at low tide and insulate the oysters. The great years of Oly production in Puget Sound began to wind down in World War II, with the loss of skilled Japanese labor to internment camps, which increased the incentive to replace Olys with faster-growing Pacifics. Then came the paper mills. News accounts from the 1950s document a virtual political war between oystermen and the mills, which discharged chemicals that destroyed beds. Lawsuits and regulations eventually reduced pollution. But the damage was done: In commercial terms, Olys were driven to near-extinction.

It was Jon Rowley, a self-described professional dreamer and a consultant to Pacific Northwest restaurants, known in the region as a prominent advocate of local, traditional food, who helped revive the Oly. By the early 1980s, Rowley recalls, Olympias were not to be had even in local restaurants. “It was something people might have heard of,” he says, “but not something they actually ate.” So Rowley went out to Shelton, to the venerable oyster business then overseen by Justin Taylor (who died last year at age 90).

The Taylor family’s ties to native oysters go back to the late 19th century, when an ancestor, J. Y. Waldrip, gained title to 300 acres of tideland. A figure very much in the Twainian tradition of knockabout frontier speculator, Waldrip had worked as a pharmacist, blacksmith, gold miner (or gambler) in Alaska and breeder of army horses in Alberta before he finally settled on oyster farming. Even during those years when the Olympias were falling out of favor, the Taylors continued growing some, mainly (as Twain might have been unsurprised to learn) for a California niche market provided by the Swan Depot and a handful of other restaurants.

A turning point of sorts in local appreciation of the shellfish—and the culmination of Rowley’s collaboration with Justin Taylor—came at Ray’s Boathouse Restaurant in Seattle one night in 1983. “We wanted to celebrate what we called ‘the return of the Olympia oyster,’” Rowley recalls. One hundred twenty guests dined on a single course—raw Olympias—washed down with sparkling wine. For most, the taste was entirely new; to Rowley, that moment signified the return of a heritage flavor. “At first you get kind of a sweet, nutty taste, and then as you chew, you get layers of flavor—they finish with this metallic, coppery taste at the end. It screams out for a clean, crisp-finishing white wine.”

I doubt there’s any better way to taste Olys than on the shores of Taylor’s Totten Inlet, in the company of Jon Rowley on a gray afternoon. Rowley scarfs down freshly shucked specimens with the gusto that Twain would have brought to the task. “Open one up and slurp it down,” he instructs. I do, chewing slowly to release the deep mineral flavor. “Nothing on them,” Rowley says. “They’re so good by themselves.” Even the no-frills aura of Swan’s seems relatively tame and domesticated compared with the experience of eating Olys straight out of cold waters freshened that morning by snowfall. Here, they belong; here, they’re perfect.

Twain, to his great regret, never returned to San Francisco after 1865. If he had, he would have found the city’s oyster culture much altered. With so many Easterners longing for briny Virginicas, merchants began sending shipments to California immediately after completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. In October of that year, the Daily Alta California reported that “the first carload of Baltimore and New York oysters in shells, cans, kegs, all in splendid order, has arrived.” A decade later, 100 freight cars of oyster seed were arriving in San Francisco annually, sustaining the cultivation of Eastern oysters in the bay.

Nevertheless, Olys would remain a distinctive element of San Francisco cuisine for years; in 1877, Scribner’s Magazine declared that “in San Francisco you win the confidence of the Californian by praising his little coppery oysters and saying [that] the true taste of the ‘natives’ is only acquired in waters where there is an excess of copper in suspension.”

These days, when Olys are to be had at Swan’s (current market price is $2 apiece), they’re most often served as a cocktail. “These are great eating,” Tom Sancimino says, handing me an Oly on the half shell, dressed with fresh tomato sauce intensified by a few drops of lemon, horseradish and Tabasco. That’s a lot of sharp, acidic flavor; still, the distinctive, metallic Oly comes through. I suspect Twain would have liked several dozen. “I never saw a more used up, hungrier man, than Clemens,” William Dean Howells, the legendary 19th-century editor of the Atlantic, once wrote of Twain. “It was something fearful to see him eat escalloped oysters.”

Twain’s final opportunity to sample Olys likely came in 1895, when a round-the-world lecture tour took him to Olympia, Washington. We don’t know exactly what dishes he enjoyed during his stop there, before embarking for Australia. But it’s easy to conjure up an image of Twain tucking into the local oysters. I like to think that the taste of this American classic, food that truly speaks of place, summoned memories of his San Francisco years; I can imagine that, as his steamer put to sea, carrying him from the West Coast he would never see again, Twain was dreaming of oysters.

Mark Richards is based in Mill Valley, California. Benjamin Drummond lives in Washington’s Northern Cascades Mountains.