The Divine Art of Tapestries

The long-forgotten art form receives a long overdue renaissance in an exhibit featuring centuries-old woven tapestries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Battle-of-Actium-tapestries-631.jpg)

Apart from crowd-pleasers such as the Dame à la Licorne (Lady with the Unicorn) series at the Musée Cluny in Paris and the “Unicorn” group at the Cloisters in New York City, tapestries have been thought of throughout the 20th century as dusty and dowdy -- a passion for out-of-touch antiquarians. But times are changing.

“The Divine Art: Four Centuries of European Tapestries in the Art Institute of Chicago,” on view at the Art Institute through January 4 and documented in a sumptuous catalog, is the latest in a flurry of recent exhibitions to open visitors’ eyes to the magnificence of a medium once prized far above painting. In Mechelen, Belgium, a landmark show in 2000 was dedicated to the newly conserved allegorical series Los Honores, associated with the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In 2004, the National Tapestry Gallery in Beauvais, France, mounted “Les Amours des Dieux” (Loves of the Gods), an intoxicating survey of mythological tapestries from the 17th to 20th centuries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art scored triumphs with “Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence” in 2002, billed as the first major loan show of tapestries in the United States in 25 years, and with the encore “Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor” in 2007.

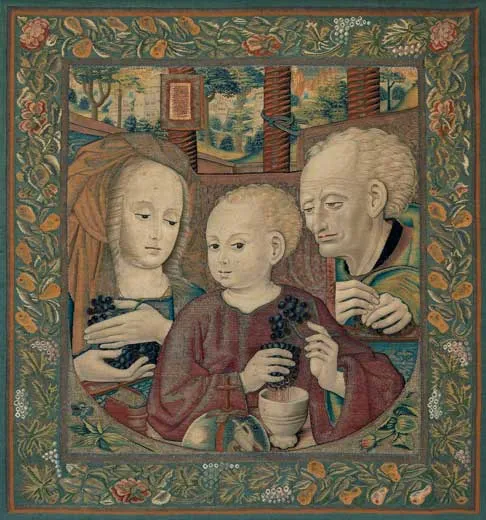

Highlights of the current show at the Art Institute include a rare Italian Annunciation from around 1500, a Flemish Battle of Actium from a 17th-century series illustrating the story of Caesar and Cleopatra, and an 18th-century French tapestry titled The Emperor Sailing, from The Story of the Emperor of China.

“We have a phenomenal collection, and it’s a phenomenal show,” says Christa C. Mayer Thurman, curator of textiles at the Art Institute. “But I don’t like superlatives unless I can document them. I feel safer calling what we have a `medium-size, significant collection.’”

Though the Art Institute does not pretend to compete with the Met or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, let alone the Vatican or royal repositories in Europe, it does own about 100 tapestries of excellent quality. On view in the show are 70 pieces, all newly conserved over the past 13 years, after decades in storage. “Please use the word conservation,” says Thurman, “not restoration. There’s a vast difference. In conservation, we conserve what is there. We don’t add and we don’t reweave.”

The value of a work of art is a function of many variables. From the Middle Ages to the Baroque period, tapestry enjoyed a prestige far beyond that of painting. Royalty and the church commissioned whole series of designs—called cartoons—from the most sought-after artists of their times: Raphael, Rubens, Le Brun. Later artists from Goya to Picasso and Miró and beyond have carried on the tradition. Still, by 20th-century lights, tapestries fit more naturally into the pigeonhole of crafts than of fine arts.

Thus the cartoons for Raphael’s Acts of the Apostles, produced by the actual hand of the artist, are regarded as the “real thing,” whereas tapestries based on the cartoons count as something more like industrial artifacts. (The cartoons are among the glories of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London). It only adds to contemporary misgivings about the medium to learn that cartoons could be “licensed” and woven in multiples, by different workshops, each time at staggering expense—as happened with both Los Honores and The Acts of the Apostles.

In their Golden Age, however, tapestries were seen to offer many advantages. They are portable, for one thing, as frescoes and wall paintings on a similar scale are not. For another, tapestries helped take the edge off the cold in large, drafty spaces. They had snob appeal, since only the richest of the rich could afford them. To hang tapestries was to show that you not only could appreciate the very best but that cost was no object. The materials alone (threads of silk and precious metals) could be worth a fortune, not to mention the massive costs of scarce, highly skilled labor. Whereas any dabbler could set up a studio and hang out a shingle as a painter, it took James I to establish England’s first tapestry factory at Mortlake, headed by a master weaver from Paris and a work force of 50 from Flanders.

Like video and unlike painting, tapestry is a digital medium. Painters compose images in lines and brushstrokes of any variety they choose, but tapestries are composed point by point. The visual field of a tapestry is grainy, and has to be. Every stitch is like a pixel.

Weaving tapestries is easiest when the objects depicted are flat, when the patterns are strong and the color schemes are simple. Three-dimensional objects, fine shadings and subtle color gradations make the work much harder. Artists like Raphael and Rubens made no concessions to the difficulties, pushing the greatest workshops to surpass themselves. But there have been train wrecks, too. For the Spanish court, Goya produced some five-dozen rococo cartoons of daily life that are counted among the glories of the Prado, in Madrid. In weavings, the same scenes appear grotesque, almost nightmarish, the faces pulled out of shape by the unevenness of the texture, eyes bleary for lack of definition.

“We know so little about the weavers,” says Thurman. “Quality depends on training. As the centuries marched on, there was always pressure for faster manufacture and quicker techniques. After the 18th century, there was a vast decline.” The Chicago show cuts off before that watershed.

After January 4, everything goes back into storage. “Yes,” says Thurman, “that’s an unfortunate fact. Due to conservation restrictions, tapestries should not be up more than three months at a time.” For one thing, light degrades the silk that is often the support for the entire textile. But there are also logistical factors: in particular, size. Tapestries are typically very large. Until now, the Art Institute has had no wall space to hang them.

The good news is that come spring, the paintings collection will migrate from the museum’s historic building to the new Modern Wing, designed by Renzo Piano, freeing up galleries of appropriate scale for the decorative arts. Tapestries will be integrated into the displays and hung in rotation. But to have 70 prime pieces on view at once? “No,” says Thurman, “that can’t be repeated immediately.”