The End of Swimsuit Design Innovation

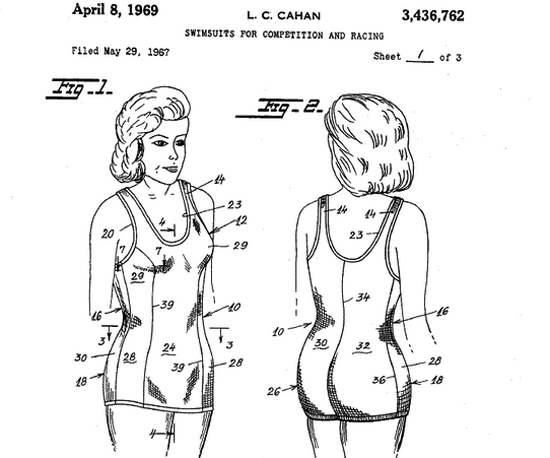

Patent drawing for Leslie C. Cahan’s 1967 application to create a better competitive swimsuit for women

In 1967, when Leslie C. Cahan filed an application with the US Patent Office for a new competitive swimsuit design for women, room for improvement was vast. In the abstract, Cahan cites problems with the swimsuits of the day—namely, that they were constructed of non-stretch material that fit loosely around the body. “Water will be trapped in the billowing or ‘bellied out’ suit and thus produce a drag that will slow down the wearer to the extent that good competitive times are substantially impossible.” One can imagine how innovation was fueled by frustration, as swimmers struggled to win races while dressed in stretch-resistent, non-porous cloth bags.

Cahan’s invention promised that water would travel through the suit material at the same velocity as it moved across the skin, greatly enhancing the athlete’s efficiency. The patent was issued in 1969, other similar inventions were introduced around the same time, and competitive swimwear has been getting tighter and stretchier in the decades since. But less than fifty years later, swimsuit technology has potentially reached a limit that design evolution rarely finds. It got so good it had to be stopped.

Speedo’s LZR racing suit, which is banned at this year’s Olympic games

Around the time of the last summer olympics, Speedo released their LZR Racer, a neck-to-ankle compression suit that boosted swimmers’ hydrodynamism beyond what would be possible simply through exceptional athletic prowess. “With the suit, Speedo steered swimming down the road taken by equipment-driven sports like golf and tennis,” Karen Crouse wrote in the New York Times. A suspicious number of record-breaking times were documented after competitors began wearing this gear, which includes drag-reducing polyurethane panels, buoyancy-enhancy material, and no seams—instead, the pieces are welded together ultrasonically.

So in 2010, the high-tech suit was banned. This year’s races aspire to take Olympic swimming back to the games’ origins, when the competition was about human strength and speed in the water, not human ingenuity and technological advancement in a research lab (well, not quite that far—Speedo has been engineering new suits, goggles, and caps that adhere to regulations while still endowing the swimmer with great gains in efficiency). Fortunately, even if the market for high-tech competitive swimwear drops off, this technology still has a place in the undergarment sector, where petrifying one’s non-aerodynamic anatomy through compression remains tantamount to success in life. Apparently it takes 20 minutes to squeeze into a Speedo LZR. No wonder I had such difficulty trying on a Spanx slip in a dressing room recently. I just didn’t set aside enough time.

Read more about Olympic swimsuit design in Jim Morrison’s story from Smithsonian.com.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)