The Essentials: Charles Dickens

What are the must-read books written by and about the famed British author?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Charles-Dickens-Oliver-Twist-631.jpg)

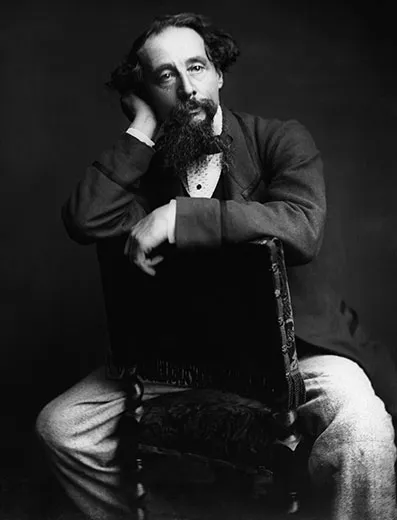

One of the most-read authors of the Victorian era, Charles Dickens wrote over a dozen novels in his career, as well as short stories, plays and nonfiction. He is probably best known for his memorable cast of characters, including Ebenezer Scrooge, Oliver Twist and David Copperfield.

Becoming Dickens, a biography released in 2011 in time for the 200th anniversary of his birth, chronicles the writer’s meteoric rise from relative obscurity as a journalist to one of England’s most adored novelists. Here, the book’s author, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, recommends five novels by Dickens and five additional books that offer insight into the writer and his work.

The Pickwick Papers (1836)

In Charles Dickens’ first novel, The Pickwick Papers, Samuel Pickwick, the founder of the Pickwick Club in London, and three of the group’s members—Nathaniel Winkle, Augustus Snodgrass and Tracy Tupman—travel around the English countryside. Sam Weller, a cockney who speaks in proverbs, joins the party as Mr. Pickwick’s assistant, adding more comedy to their adventures, which include romances, hunting outings, a costume party and jail stays.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: This started out as a collection of monthly comic sketches and only slowly developed into something more like a novel. A huge craze at the time of its original publication in 1836-37—it produced as many commercial spinoffs as any modern film—it still has the power to reduce a reader to tears of laughter. As a comic double-act, Mr. Pickwick and Sam Weller are as immortal as Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello.

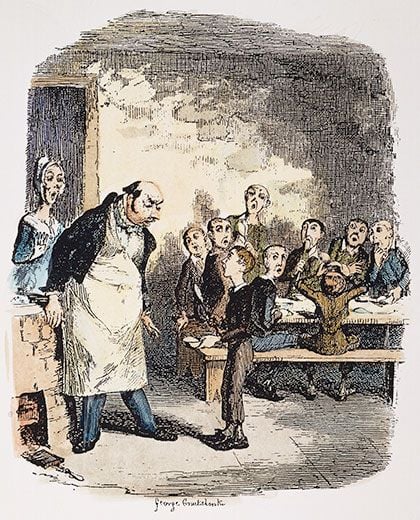

Oliver Twist (1837-39)

When orphan Oliver Twist loses a bet and brazenly asks for more gruel, he is kicked out of his workhouse and sent to serve as an apprentice to an undertaker. On the run after a scuffle with another of the undertaker’s apprentices, Oliver Twist meets Jack Dawkins, or the Artful Dodger, who brings him into a gang of pickpockets trained by a criminal named Fagin.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: “Please, sir, I want some more”—When Dickens wrote that at the start of his first fully planned novel, he was probably hoping that the sentiment would be echoed by his readers. He wasn’t disappointed. His waif-like hero may be a little passive for modern tastes, but Oliver’s adventures with Fagin and the Artful Dodger quickly passed from fiction into folklore. There may be fewer jokes than in The Pickwick Papers, but Dickens’ satire on attitudes toward poverty remains as relevant as ever.

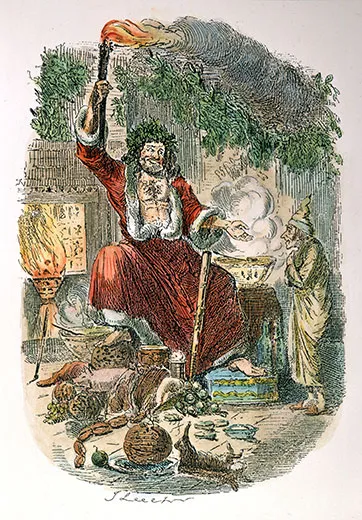

A Christmas Carol (1843)

Ebenezer Scrooge’s deceased business partner Jacob Marley and three other spirits—the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come—visit him in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The spirits tour Scrooge through scenes of past and present holidays. He even gets a preview of what is in store for him should he continue on his miserly ways. Scared straight, he wakes from the dream a new man, joyful and benevolent.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: This isn’t a novel, strictly speaking, but it is still one of the most influential stories ever written. Since A Christmas Carol’s first appearance in 1843, it has been reproduced in so many different forms, from Marcel Marceau to the Muppets, that it is now as much a part of Christmas as turkey or presents, while words like “Scrooge” are deeply rooted in the national psyche. At once funny and touching, it has become one of our most powerful modern myths.

Great Expectations (1860-61)

This is the story of Pip, an orphan who has eyes for Estrella, a girl of a higher class. He receives a fortune from Magwitch, a fugitive he once provided food for, and puts the money toward his education so that he might gain Estrella’s favor. Does he win over the girl? I won’t spoil the ending.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: A slim novel that punches well above its weight, Great Expectations is a fable about the corrupting power of money, and the redeeming power of love, that has never lost its grip on the public imagination. It is also beautifully constructed. If some of Dickens’ novels sprawl luxuriously across the page, this one is as trim as a whippet. Touch any part of it and the whole structure quivers into life.

Bleak House (1852-53)

Dickens’ ninth novel, Bleak House, centers around Jarndyce and Jarndyce, a drawn-out case in England’s Court of Chancery involving one person who drew up several last wills with contradicting terms. The story follows the characters tied up in the case, many of whom are listed as beneficiaries.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: Each of Dickens’ major novels has its admirers, but few can match Bleak House for its range and verve. It is at once a remarkable verbal photograph of mid-Victorian life and a narrative experiment that anticipates much modern fiction. Some of its scenes, such as the death of Jo, the crossing sweeper, tread a fine line between pathos and melodrama, but they have a raw power that was never equaled even by Dickens himself.

The Life of Charles Dickens (1872-74), by John Forster

Soon after Dickens died from a stroke in 1870, John Forster, his friend and editor for more than 30 years, gathered letters, documents and memories and wrote his first biography.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: The result was patchy, pompous and sometimes reads more like a disguised autobiography. One reviewer sniffed that it “should not be called The Life of Dickens, but the History of Dickens’ Relations to Mr. Forster.” But it also contained some remarkable revelations, including the fragment of autobiography in which Dickens first told the truth about his miserable childhood. It is the foundation stone for all later biography.

Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906), by G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, an English writer in the early 20th century, devoted whole chapters of his study of Dickens to the novelist’s youth, his characters, his debut novel The Pickwick Papers, America and Christmas, among other topics.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: If Dickens invented the modern celebration of Christmas, Chesterton almost single-handedly invented the modern celebration of Dickens. What he relishes above all in Dickens’ writing is its joyful prodigality, and his own book comes close to matching Dickens in its energy and good humor. There have been many hundreds of books on Dickens written since Chesterton’s, but few are as lively or significant. Almost every sentence is a quotable gem.

The Violent Effigy: A Study of Dickens’ Imagination (1973, rev. ed. 2008), by John Carey

When the University of Oxford expanded its English curriculum to include literature written after the 1830s, professor and literary critic John Carey began to deliver lectures on Charles Dickens. These lectures eventually turned into a book, The Violent Effigy, which attempts to guide readers, unpretentiously, through Dickens’ fertile imagination.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: This brilliantly iconoclastic study starts from the premise that “we could scrap all the solemn parts of Dickens’ novels without impairing his status as a writer,” and sets out to celebrate the strange poetry of his imagination instead. Rather than a solemn treatise on Dickens’ symbolism, we are reminded of his obsession with masks and wooden legs; rather than viewing Dickens as a serious social critic, we are presented with a showman and comedian who “did not want to provoke … reform so much as to retain a large and lucrative audience.” It is the funniest book on Dickens ever written.

Dickens (1990), by Peter Ackroyd

This tome of 1,000-plus pages by Peter Ackroyd, a biographer who has also made Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot his subjects, captures the nonfiction—or life and times of Charles Dickens—that the writer often wove into his fiction.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: When Peter Ackroyd’s huge biography of Dickens was first published, it was attacked by some reviewers for what they saw as its self-indulgent postmodern tricks, including fictional dialogues in which Ackroyd conversed with his subject. Yet such passages are central to a book in which Ackroyd involves himself sympathetically in every aspect of Dickens’ life. As a result, you finish this book feeling not just that you know more about Dickens, but that you actually know him. A biography that rivals Dickens’ novels for its rich cast of characters, sprawling plot and unpredictable swerves between realism and romance.

Other Dickens: Pickwick to Chuzzlewit (1999), by John Bowen

John Bowen, now a professor of 19th-century literature at England’s University of York, casts his eye toward Dickens’ early works, written from 1836 to 1844. He argues that novels such as The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Martin Chuzzlewit redefined fiction in the way that they broach politics and comedy.

From Douglas-Fairhurst: During Dickens’ lifetime they were by far his most popular works, and it was only in the 20th century that readers developed a preference for the later, darker novels. John Bowen’s study shows why we should return to them, and what they look like when viewed through modern critical eyes. It is a superbly readable and detailed piece of literary detective work.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)