The Films That Led to Game Change

The HBO film has roots in two acclaimed documentaries that covered the 1992 and 1960 presidential elections

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120309041103War_Room_006-550w1.jpg)

Well before its premiere this Saturday on HBO, Game Change was generating controversy. A docudrama about how Sarah Palin was selected as John McCain’s running mate in his campaign for President, the film was adapted from the best-selling book by journalists Mark Halperin and John Heilemann. The cable broadcaster trumpeted the film’s accuracy in press releases, stating that “The authors’ unprecedented access to the players, their wide-ranging research and the subject matter itself gave the project a compelling veracity that has become a signature of HBO Films.” Even though there’s no such thing as bad publicity, the film quickly came under attack, with Palin aides calling it inaccurate and Game Change screenwriter Danny Strong defending his work as “as fair and accurate a telling of this event that we believe could possibly be done in a movie adaptation.”

The biggest surprise about Game Change is that it’s more about campaign strategist Steve Schmidt (played by Woody Harrelson) than about either of the two candidates. (Actor Ed Harris plays McCain.) Much of the film is told from Schmidt’s point-of-view, which means that he gets to analyze the candidates’ motives and abilities. Since Palin and McCain declined to be interviewed for the film, Game Change can’t get into their minds the way it does with Schmidt. And the candidates can’t rebut his account of what happened.

Hollywood screenwriters love flawed heroes, and if there’s one theme that ties together films about campaigns and politicians, it’s the idea that candidates are afflicted with hamartia, a tragic flaw that determines their fates. In films as old as Gabriel Over the White House (1932) and as recent as The Ides of March (2011), candidates and politicians alike are pried apart on screen for viewers to inspect.

Ironically, it’s usually the candidate’s willingness to compromise that brings about his or her downfall. On the one hand, everyone wants politicians to have integrity. But isn’t the ability to compromise central to politics?

James Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Gary Cooper in Meet John Doe (1941), Spencer Tracy in State of the Nation (1948), Henry Fonda in The Best Man (1964), Robert Redford in The Candidate (1972)—all lose support when veer away from their personal beliefs in order to attract voters. The Great McGinty (1940), which won director and writer Preston Sturges an Oscar for his screenplay, offers a wonderful twist on this idea of a character flaw. A bum-turned-party hack (Brian Donlevy as McGinty) is elected governor in a crooked campaign, only to throw his state’s politics into turmoil when he decides to go straight.

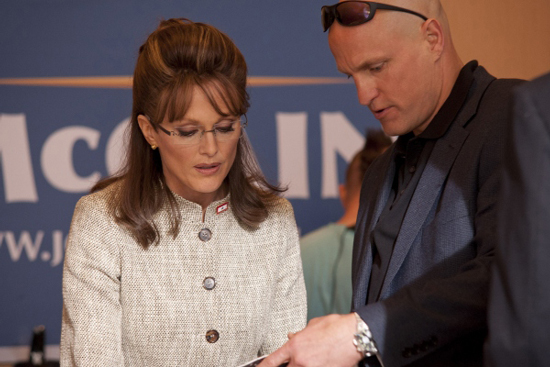

Julianne Moore as Sarah Palin and Woody Harrelson as Steve Schmidt in HBO Films' Game Change.

The theme is muted but still present in Game Change. Palin flounders when she tries to obey campaign strategists. Only by returning to her roots can she succeed as a candidate. What I found more interesting in Game Change is how the filmmakers borrowed so many scenes and settings from The War Room.

Directed by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker, The War Room (1993) gave moviegoers unprecedented access to the people who ran Bill Clinton’s Presidential campaign. By concentrating on strategist James Carville and communications director George Stephanopoulos, The War Room showed how campaigns are waged, decisions made, and the press manipulated. (The Criterion Collection has just released The War Room on Blu-Ray and DVD.)

The War Room has inevitable parallels with Game Change. Both films deal with scandals that were fed and amplified by the media; both focus on conventions and debates. And both concentrate not on the candidates, but on their handlers—in previous films largely objects of scorn. But The War Room is a documentary, not a docudrama. Hegedus and Pennebaker weren’t following a script, they were trying to capture events as they happened.

Tellingly, Pennebaker admits that the filmmakers won access to the campaign’s war room in part because Carville and Stephanopoulos felt “somehow we were on their side.” Pennebaker was one of the cinematographers on the groundbreaking documentary Primary, in my opinion the film that first opened the political process to the public. An account of a Wisconsin primary in 1959 between Senators Hubert H. Humphrey and John F. Kennedy, Primary took viewers behind the scenes to see how campaigns actually operated.

Primary set up a contrast between Humphrey, shown as isolated, out of touch, and Kennedy, a celebrity surrounded by enthusiastic crowds. It was a conscious bias, as Pennebaker told me in a 2008 interview. “Bob and all of us saw Kennedy as a kind of helmsman of a new adventure. Win or lose we assumed he was the new voice, the new generation.” As for Humphrey: “We all saw him as kind of a nerd.”

As influential as Theodore White’s The Making of the President, 1960, Primary set a template for every subsequent film about campaigns.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)