The First Major Museum Show to Focus on Smell

“The Art of the Scent” recognizes and celebrates fragrance as a true artistic medium rather than just a consumer product

![]()

Installation view of The Art of the Scent exhibition at the Museum of Art and Design in New York. (image: Brad Farwell)

While walking through the Museum of Art and Design’s exhibition “The Art of the Scent (1889-2012)” my mind was flooded with memories of a nearly forgotten childhood friend, an ex-girlfriend and my deceased grandmother. It was a surprisingly powerful and complex experience, particularly because it was evoked in a nearly empty gallery by an invisible art form—scent. It’s often cited that smell is the sense most associated with memory (both are processed by the brain’s limbic system), and the iconic fragrances exhibited in “The Art of the Scent” are likely to take visitors on their own private jaunts down memory lane. But it might not lead where they expect.

Like any art form or design discipline, the creation of a scent is the result of experimentation and innovation. Yet, perfume and cologne are rarely appreciated as the artfully crafted designs they are. “The Art of the Scent” is the first major museum exhibition to recognize and celebrate scent as a true artistic medium rather than just a consumer product. The 12 exhibited fragrances, chosen by curator Chandler Burr to represent the major aesthetic schools of scent design, include Ernest Beaux’s Modernist Chanel No.5 (1921); the Postmodern Drakkar Noir (1982) by Pierre Wargnye ; and Daniela Andrier’s deconstructed fragrance Untitled (2010). Perhaps most significantly, the exhibition begins with the first fragrance to incorporate synthetic raw materials instead of an exclusively natural palette, thereby truly transforming scent into an art: Jicky (1889), created by Aimé Guerlain. Unfortunately, this fragrant historiography will initially be lost on the average visitor because while scent may indeed be the best sense for provoking memory, it is the worst sense for conveying intellectual content. When we smell something—good or bad—our reaction is typically an automatic or emotional response. Such a reaction doesn’t lend itself particularly well to critical analysis. One of the greatest challenges facing Burr, who wrote the “Scent Notes” column for the New York Times and the book The Emperor of Scent, was to get visitors to move beyond their initial emotional responses and memories and to think critically about scent design.

Or perhaps scent “composition” is a better word. Like a musical chord resonating in the air until it fades away, scent evolves over time until it too fades. And like a chord, scents are composed of three harmonic “notes.” The “top note” is the first impression of the scent and is the most aggressive, the “middle note” is the body of the scent, and the “base note” lingers after the other notes dissipate, giving the fragrance a depth and solidity. However, there is an enormous industry based around designing and marketing commercial fragrances that includes everything from the shape of the bottle to the celebrity endorsement to the samples at a department store. These extraneous characteristics can also shape our perception of the scent, and sometimes even shape the scent itself. For example, the “top note” has become more important over time because of the aggressive way that perfumes are typically sold and sampled in contemporary department stores. First impressions are more important than ever. “The Art of the Scent” strips all of that away. By isolating pure scent and presenting it in a museum setting, Burr hopes to do for scent what had been done for photography over the last 80 years—raise it to a level equal with painting and other traditional fine arts. It’s an ambitious goal that required exhibition designers Diller Scofidio + Renfro to address a fascinating question: how does a museum present art that you can’t see?

Luckily DSR are familiar with both museums and the ephemeral. Although they are perhaps known as the architects behind Manhattan’s High Line, DSR built their career designing installations and exhibitions in galleries and became known for questioning the role of the museum. Their buildings destabilize architecture by cultivating ephemerality and creating atmospheric effects. These ideas are most apparent in their 2002 Blur Building, an enormous scaffolding-like structure supporting continuously spraying misters that give the building the appearance of a floating cloud. The architects called it “immaterial architecture.”

The fragrance-releasing “dimples” designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (left image: DSR; right image: Brad Farwell)

It makes sense then that DSR’s installation for “The Art of the Scent” embraces the ephemeral purity of olfactory art itself. Their minimalist exhibition is, like any good minimalist work, more complex than it first appears. The architects lined three walls of the nearly empty gallery space with a row of gently sloping, almost organic “dimples.” Each identical dimple is just large enough to accommodate a single visitor, who upon leaning his or her head into the recessed space is met with an automatic burst of fragrance released by a hidden diffusion machine. I was told the burst doesn’t represent the scents’ “top notes” as one might expect, but more closely resembles the lingering trail of each commercial fragrance—as if a woman had recently walked through the room wearing the perfume. The scent hovers in the air for a few seconds then disappears completely. And no one has to worry about leaving the exhibition smelling like a perfume sample sale because every exhibited fragrance has been specially modified to resist sticking on skin or clothes. The ephemerality of perfume is reinforced by the illuminated wall texts explaining each scent, which periodically disappear completely, leaving the gallery devoid of anything but pure olfactory art.

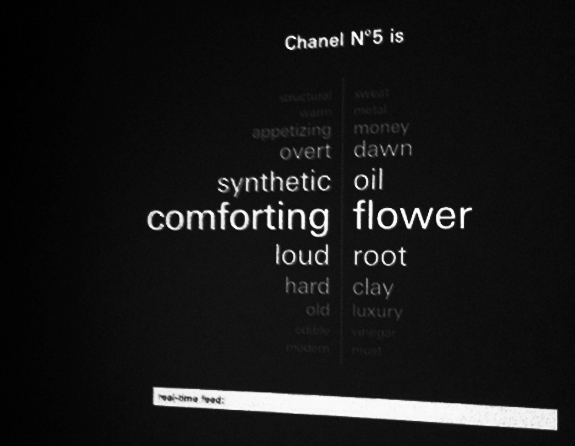

A wall projection showing Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s custom “Art of the Scent” iPad app illustrates that “comforting” and “flower” were the most popular descriptions of Chanel No.5

The exhibition also includes an interactive salon where the scents can be experienced in a more social setting. Using a custom iPad app designed by DSR, visitors select an adjective and noun to describe each scent, and as their opinions are logged, a collective impression of the scent is revealed as a projected word cloud (see above image). It’s a simple conceit but a critical one that helps fulfill one of the goals of the exhibition—to provide a vocabulary that helps non-experts understand and critique olfactory art. The primary mission of the Museum of Art and Design is to educate the public on the intersection of art, craftsmanship and design. Their exhibition programs are carefully curated to “explore and illuminate issues and ideas, highlight creativity and craftsmanship, and celebrate the limitless potential of materials and techniques when used by creative and innovative artists.” In this respect, “The Art of the Scent” is a success. It re-introduces something familiar to everyone in the unfamiliar context of aesthetic and historical movements. Though I may have entered the exhibition thinking of lost love, I left pondering the nature of harmonic fragrances and the complexity of creating an art history of smells.

“The Art of the Scent” runs until March 3, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)