The Grand Women Artists of the Hudson River School

Unknown and forgotten to history, these painters of America’s great landscapes are finally getting their due in a new exhibition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hudson-River-Mellen-FieldBeach-631.jpg)

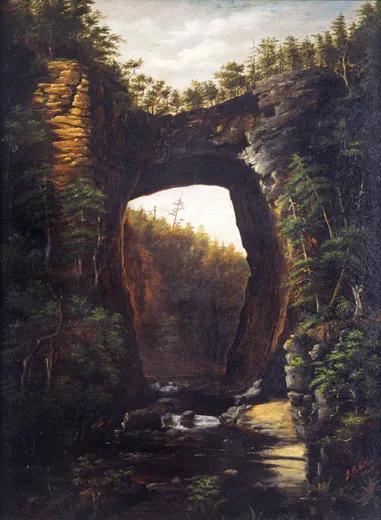

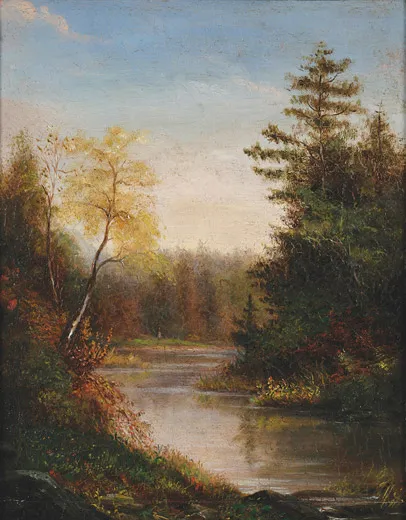

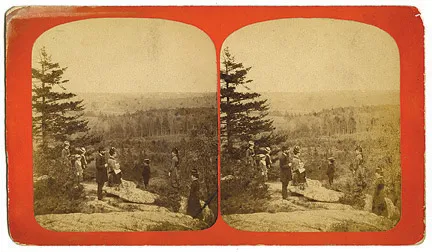

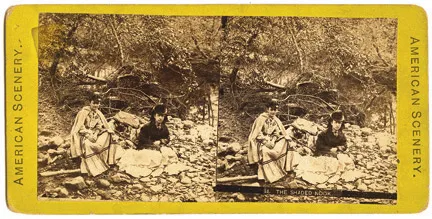

When Americans took to travel and tourism in the mid-19th century, exploring the great landscape around them brought particular challenges, especially to women, who were constrained by the strictures of proper behavior and dress. But that didn’t stop a coterie of female artists like Susie M. Barstow, who not only climbed the principal peaks of the Adirondacks, the Catskills and the White Mountains, but also sketched and painted along the way—sometimes “in the midst of a blinding snow-storm,” according to one account.

If you have never heard of Barstow, you are not alone. The curators of “Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School,” a little exhibition in upstate New York that features works by Barstow and her cohorts, have set themselves the enormous goal of rewriting a chapter in American art history—to include these artists.

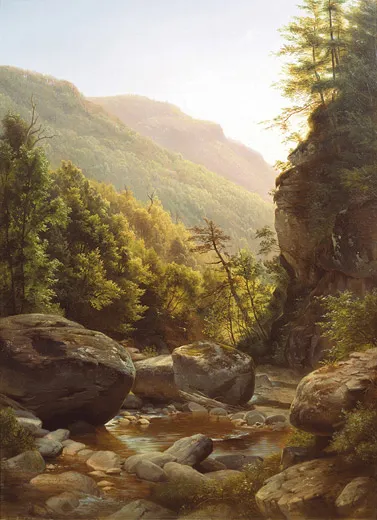

These women ventured on their own or alongside male relatives into the wilderness, painting the glorious scenery that inspired America’s first art movement. And as the show on view since May at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in Catskill, New York, amply demonstrates, they made works that are just as awe-inspiring as those of their male counterparts.

“I was so moved by Harriet Cany Peale’s Kaaterskill Clove,” says Elizabeth Jacks, director of the Cole site, which honors the founder of the Hudson River school. “When you see it in person, it looks like it belongs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Or perhaps other museums. Curators Nancy J. Siegel, an art history professor at Towson University in Maryland, and Jennifer C. Krieger, managing partner of Hawthorne Fine Art in New York City, have had from the start ambitions beyond mounting “the first known exhibition to focus solely on these women.”

Who are these women, so long ignored, that even experts like Nancy G. Heller, author of Women Artists: An Illustrated History,” whose fourth edition was published in 2004, make no mention of them?

Often they were the sisters, daughters and wives of better-known male artists. Harriet Cany Peale, at first a student of Rembrandt Peale, became his second wife. Sarah Cole was Thomas Cole’s sister; her daughter Emily Cole is also in the exhibit. Jane Stuart called Gilbert Stuart “father.” Evelina Mount was niece to William Sidney Mount, while Julia Hart Beers was the sister of two artists, William Hart and James Hart. Others—Barstow, Eliza Greatorex and Josephine Walters, among them—had no relatives in the art world.

Although women were educated in the arts, being a professional artist in the 19th century was the province of men. Most art academies didn’t admit women, and neither did the clubs that linked artists with patrons. The requisite figure-drawing classes, which featured nude models, were off-limits to most women. One artist in the exhibition, Elizabeth Gilbert Jerome, was forbidden from making art, an activity considered by some to be so unladylike that when she was 15, her stepmother burned all of her drawings. Only at age 27 was Jerome able to begin studying drawing and painting.

Undaunted, these talented women persevered, sometimes with the help and support of men like Cole and Fitz Henry Lane, who both gave instruction to women. Some women of the period exhibited their work at venues like the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Brooklyn Art Association. And others, like Greatorex, who was widowed at an early age, even managed to support themselves and their families with sales of their art.

Though their paintings were largely left out of the story of American art, the exhibition displays work that reflects the same romantic sensibility, respect for balance, luminosity and love of picturesque landscapes as those of artists like Cole, Asher B. Durand and Frederic Church. “These paintings aren’t particularly feminine; they’re not flowery,” Jacks says. “If you walked into the show, you’d just say these are a group of Hudson River school paintings. They are part of the movement. It’s our own problem that we haven’t included them in the history of the Hudson River school.”

Jacks says the show came about after a board member and a former board member of the Cole site separately asked, “What about the women?” She contacted Siegel, with whom she had worked previously. Siegel, who had already been working on the subject, then called Krieger, who she thought would know which private collectors owned works by these artists. Krieger, whose interests include feminist art history, was delighted: on her own, she had hired an assistant to help her research this area. “We had all conceived it separately, on a parallel track,” she explains.

According to Jacks, visitors to the show are amazed by the quality achieved by artists wholly unfamiliar to them. “The number one question we’ve been asked is ‘why hasn’t anyone done this before?’ I don’t know how to answer that,” she says.

The exhibition has provoked another desired response, though. In hopes of creating a larger exhibition that might travel to other venues, the curators are in search of more works, They have already added to their list of potential works to borrow and artists to include. Among the artists new to Krieger are Emma Roseloe Sparks Prentice, Margaretta Angelica Peale and Rachel Ramsey Wiles (mother of Irving Wiles).

The exhibition in Catskill runs through October.

And then—after the paintings, drawings and photographs are returned to their owners—Siegel and Krieger will begin work on the larger task of ensuring that these women become part of the American art narrative. To add that chapter, says Siegel, “there is much more work to be done.”

Editor's Note -- July 29, 2010: An earlier version of this story indicated that the "Remember the Ladies" exhibition would be moving to the New Britain Museum of American Art. It is no longer scheduled to be shown at that museum.