The Halloween Tradition Best Left Dead: Kale as Matchmaker

Be happy this Scottish tradition is passé, your future marriage may have depended on it

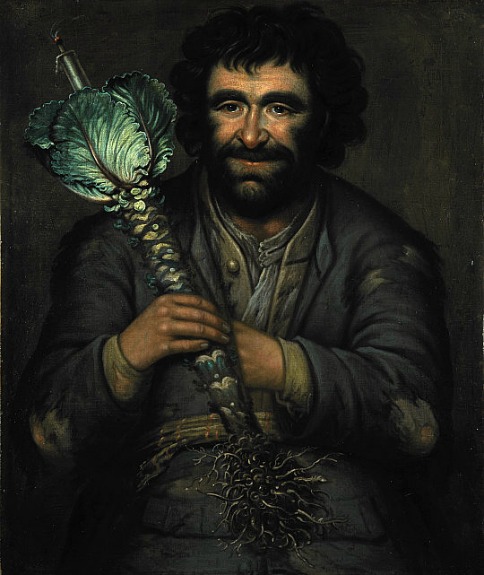

Meet the Cromartie Fool, the goofy man holding a kale stock. According to Celtic tradition, it was believed that this jester presided over Halloween festivities—many of which involved single men and women uprooting kale stalks to determine their future. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The commemoration of the last day of the ancient Celtic calendar was a major influences on how we celebrate Halloween, but one significant tradition has (thankfully?) not survived. Kale, that leafy salad green, was a tool of marriage divination, identifying life partners for men and women in ancient Scotland and Ireland.

But first, some context: According to the Celtic calendar, on the morning of November 1, spirits and the supernatural “bogies” were free to roam the night of the 31st and into the morning as the new year represented the transition between this world and the otherworld. To fend off the spirits and to celebrate the coming year, Scottish youths participated in superstitious games on Halloween night that were thought to bring good fortune and predict the future marital status of partygoers.

Scottish bard Robert Burns describes the typical festivities for the peasantry in the west of Scotland in his poem, “Halloween,” originally published in both English and Scots in 1785. The 252-line poem follows the narrative of 20 characters and details many—often confusing—folk practices: Burning nuts, winnowing the corn, and the cutting of the apple:

“Some merry, friendly, country-folks,

Together did convene,

To burn their nuts, and pile their shocks of wheat,

And have their Halloween

Full of fun that night.”

Also included among the party games mentioned in Burns’ poem is our first Halloween kale matchmaking activity, known as ”pou (pull) the stalks.”

1) Pou (Pull) the Stalks

In this Scottish tradition, instead of trick-or-treating, young, eligible men and women were blindfolded and guided into a garden to uproot kale stalks. After some time digging in the dirt, the piece of kale selected was analyzed to determine information about the participant’s future wife or husband.

In Burns’ poem, for example, the character of Willie, tries his luck and pulls a stalk as curly as a pig’s tail. He isn’t too happy about it:

“Then, first and foremost, through the kail,

Their stocks maun a’ be sought ance;

They steek their een, and graip and wale,

For muckle anes and straught anes.

Poor hav’rel Will fell aff the drift,

And wander’d through the bow-kail,

And pou’t, for want o’ better shift,

A runt was like a sow-tail,

Sae bow’t that night.”

The analysis was pretty literal according to Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween by David J. Skal—meaning poor Willie’s curly-Q’d root didn’t look too promising. Characteristics of the stalk were thought to reveal signs about the potential partner: A short and stunted stalk meant just that for the player’s future mate. Tall and healthy, withered and old, and so on—even the kale’s flavor was thought to hint at the disposition of the future spouse (bitter, sweet, etc.). The amount of dirt clinging to the stalk post pou was believed to determine the size of the dowry or fortune the participant should expect from their husband or wife. A clean root meant poverty was in the cards.

Skal excerpts a song associated with the tradition from Bright Ideas for Hallowe’en, published in 1920 that breaks down the rules for young ladies and gentlemen:

“A lad and lassie, hand in hand,

Each pull a stock of mail;

And like the stock, is future wife

Or husband, without fail.

If stock is straight, then so is wife,

If crooked, so is she;

If earth is clinging to the stock,

The puller rich will be.

And like the taste of each stem’s heart,

The heart of groom or bride;

So shut your eyes, and pull the stocks,

And let the fates decide.”

2) Cook Up Some Colcannon

If you’re not satisfied with letting the “fates” determine the man or woman you will spend the rest of your life with, perhaps this Irish tradition may interest you. For Hallowe’en—what Christianity would later call All Hallows’ Eve—kale was used in the traditional dish, colcannon, or “white-headed cabbage” when translated from its Gaelic roots cal ceannann’. Charms hidden in the mush of cabbage, kale and chopped onions, were thought to determine who at the table would be the next to tie the knot. If you were lucky enough to find a ring concealed in your meal, no longer would you spend your Halloween dinner single and sighing—wishing you’d find a piece of metal in your food. The other hidden object was a thimble, which meant the life of a spinster for the lady lucky enough to discover it. Eating the dinner trinket-free seems to be the best of the three situations, but I suppose it depends on who you’re asking. If the Halloween dinner were up to me, the only thing on the menu would be candy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)