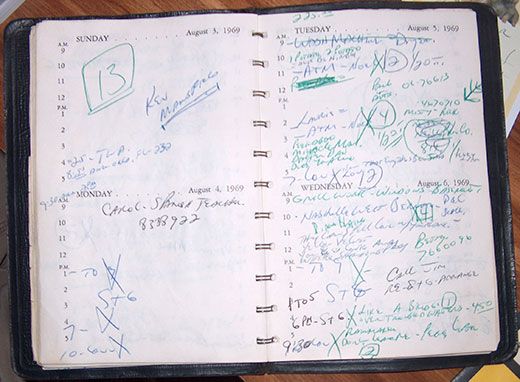

The Hidden History of a Rock ’n’ Roll Hitmaker

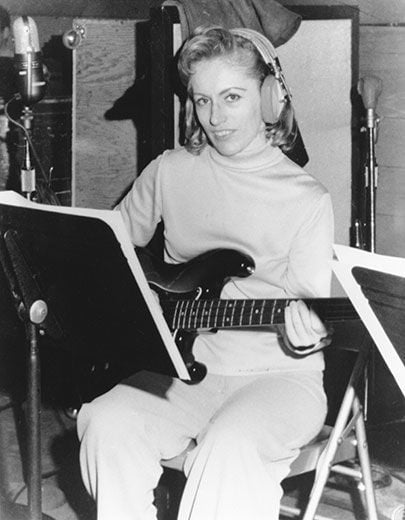

Bassist Carol Kaye blazed her own trail, as the only female studio musician to record some of the greatest songs of the ’60s and ’70s

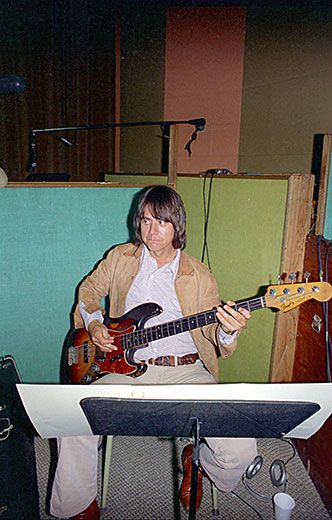

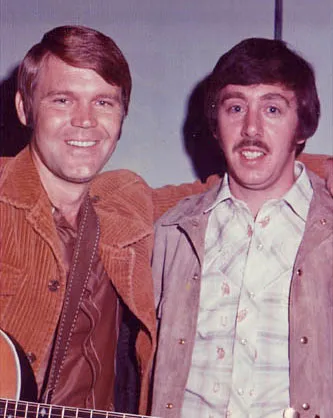

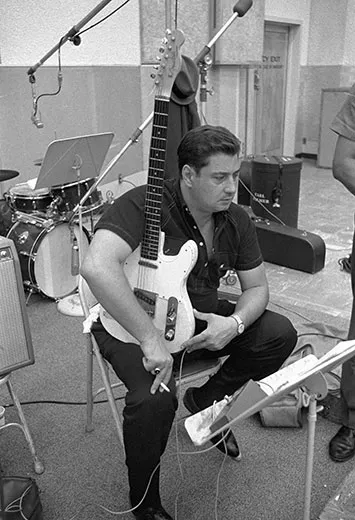

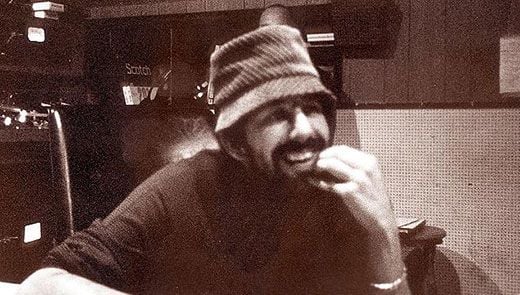

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Wrecking-Crew-Carol-Kaye-Bill-Pitman-631.jpg)

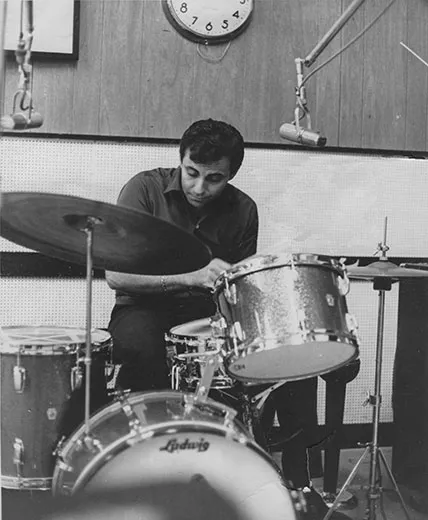

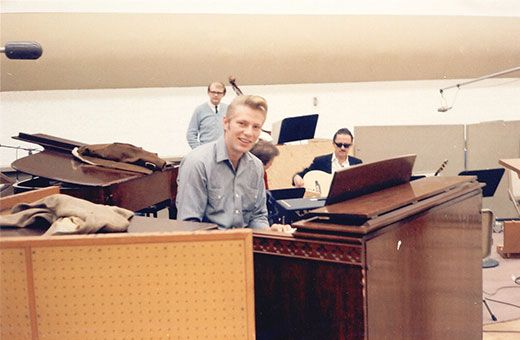

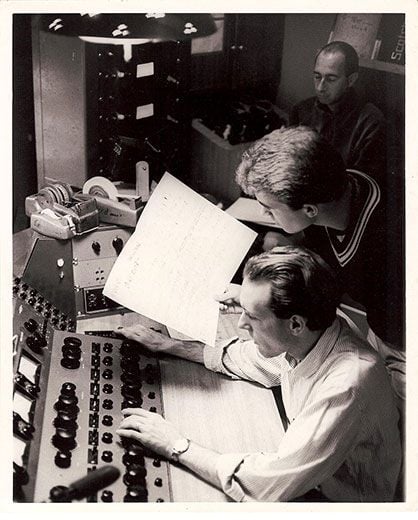

Like the clarion call of a medieval trumpet, the money to be made in the record business at the dawn of the ’60s in Los Angeles would prove to be an irresistible draw to every kind of hopeful. Essentially music’s version of the California Gold Rush, the varied and rapidly growing number of opportunities to make some cash and a name in rock and roll began to attract talent, ambition, greed and egotism, all in seemingly equal measure. And from this diverse migratory mix—aside from the scores of singers, songwriters and others who made the journey—there evolved a core clique of instrument-playing sidemen who gradually began to stand out from the rest. These musicians not only had the willingness and ability to play rock ’n’ roll (two qualities that set them uniquely apart from other session musicians in town, both old and new); they also instinctively knew how to improvise in just the right doses to make a given recording better. To make it a hit. Which naturally put their services in the highest of demand: producers wanted hits. It also, over time, provided them with a nickname that mirrored their emergence as the new, dominant group of determined young session players who were taking over the growing rock- and-roll side of things: the Wrecking Crew.

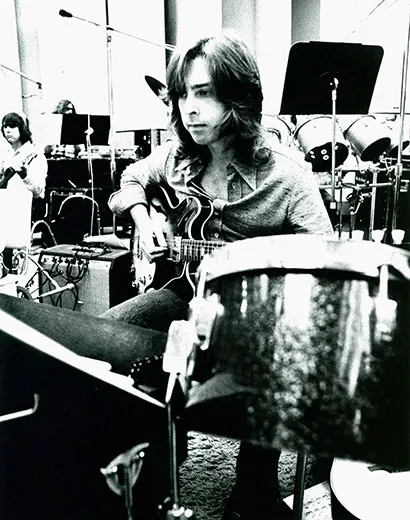

If a rock song came out of an L.A. recording studio from about 1962 to 1972, the odds are good that some combination of the Wrecking Crew played the instruments. No single group of musicians has ever played on more hits in support of more stars than this superbly talented, yet virtually anonymous group of men—and one woman.

By the time the early ’50s rolled around, Carol Smith knew exactly what she wanted to do with her life. She wanted to keep playing guitar.

Her mentor, Horace Hatchett—an esteemed instructor and graduate of the Eastman School of Music—had helped her pick up some local work around the Long Beach area, and she had flourished. Starting with about one booking a week at the almost unprecedented age of only 14, Smith rapidly gained acceptance during her high school years among the area’s veteran players. She soon found herself in regular demand for live work at a variety of dances, parties and nightclubs in the South Bay region.

Never satisfied with the status quo, the independent Smith took additional steps on her own to further her musical education by frequently taking the short train ride up to Los Angeles to see acts like Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and many of the popular big bands of the era. It was in watching these top-flight pros that Smith began to imagine herself being a part of their world.

Just after high school, Carol caught on for a couple of years with the popular Henry Busse Orchestra, with whom she traveled the country playing dances and other events. She also ended up marrying Al Kaye, the band’s string bass player, permanently taking his last name. Soon thereafter came a son and a daughter.

However, by 1957, with the big band gig having come to a close sometime earlier (in 1955 Busse had fallen over dead from a massive heart attack during, of all things, an undertakers’ convention), Kaye found herself at a crossroads. Despite her best efforts, her short marriage had not worked out, due in large part to a considerable age difference and her husband’s penchant for drinking a little too much wine. Kaye was also no longer on the road making regular money, either. And she now had two kids and a mother to support, all on a single income.

Deciding she needed to be practical, Kaye found a day job as a high-speed technical typist within the avionics division of the giant Bendix Corporation. Though the pay was good, she simultaneously moonlighted on guitar sometimes five or six nights a week in the jazz clubs around Los Angeles. An exhausting schedule for anyone, let alone a working mother of two. But laying down some bebop fed Carol Kaye’s musical soul; there was no way to shake that. And the more she played, the more her reputation grew within the higher echelons of the West Coast jazz world.

Unfortunately for Kaye, however, with rock ’n’ roll’s popularity on the rise in the late ‘50s, the number of Southern California clubs catering solely to jazz patrons began to dwindle in direct proportion. It made it almost impossible for an up-and-comer like Kaye to earn a living playing full time, which had always been her dream. But she persevered, creating the music she loved by night, hoping for the best by day.

One evening, while Kaye took a short break from laying down her inventive lead guitar fills as part of the saxophonist Teddy Edwards’ combo at the Beverly Caverns nightclub, a man she had never seen before approached her with a very unexpected question.

“Carol, my name is Bumps Blackwell,” he said, extending his hand. “I’m a producer here in L.A. I’ve been watching you play tonight and I like your style. I could use you on some record dates. Interested?”

A more-than-surprised Kaye looked at Blackwell and then at her bandmates, not sure what to think, say or do. She had certainly heard all the rumors that taking on non-jazz recording studio work would be the kiss of death for someone trying to make a career out of playing live bebop. Once someone left, they tended to never come back. And true jazzers tended to look down on those who played what they sometimes referred to as “people’s music.” It took time to build a name in the clubs, too. But Kaye also knew she needed to get away from her job at Bendix as soon as possible. She had grown to dislike it. Maybe going into studio work would be a chance to finally establish a solid, well-paying career playing music.

With a deep breath, a hesitant Kaye agreed to take the plunge.

“He’s a new singer out of Mississippi that I just started producing,” Blackwell continued, delighted that she was interested in coming aboard.

“His name is Sam Cooke.”

After the serendipitous encounter, Kaye did indeed start working studio dates for Blackwell’s protégé. And the mental transition on her part in moving from dedicated jazzer to rock guitarist proved to be smoother than she expected. Though Kaye had at first never heard of Cooke (few had at the time), she found herself enthused by the caliber of musicians hired to play alongside her. As she gracefully slid into her new role, her particular specialty became adding tasteful and appropriate guitar fills at important points during the songs.

To Kaye’s surprise, playing on Cooke’s hits at the turn of the decade like “Summertime (Pt. 2)” and “Wonderful World” didn’t seem all that different from playing live in the clubs, either. A quality song was a quality song. And her work began to lead directly to additional offers from other well-known producers and arrangers, including Bob Keane (“La Bamba” by Ritchie Valens), H. B. Barnum (“Pink Shoe Laces” by Dodie Stevens), and Jim Lee (“Let’s Dance” by Chris Montez). Word habitually traveled quickly among recording studios whenever a hot new player arrived on the scene. The comparatively lucrative studio pay also proved to be a godsend for Kaye. She soon found herself earning a steady enough income at union scale to finally quit her suffocating day job for good.

***

In 1963, Betty Friedan, a freelance magazine writer and suburban New York housewife, dismayed by the prevalence of what she called “the problem that has no name,” wrote the book The Feminine Mystique. In her expository essay, Friedan analyzed the trapped, imprisoned feelings that she believed many women (including herself) secretly held regarding their roles as full-time homemakers. Friedan vehemently argued that women were as capable as men to do any kind of work or to follow any kind of career path and that they would be well served to recalibrate their thinking accordingly.

Some considered it a call to arms; others found it to be an outrage. Either way, Friedan’s groundbreaking treatise not only ignited a nationwide firestorm of controversy and debate, it also became an instant bestseller, in the process helping to launch what came to be known as the “second stage” of the women’s movement.

With Kaye self-reliant from an early age, it never entered her mind that she couldn’t perform either in the same profession or at the same level as men. She had played alongside many women in her earlier jazz days, when greats like the organist Ethel Smith, the pianist Marian McPartland and the alto saxophonist Vi Redd were at the height of their careers. So the notion of being a woman who happened to play guitar seemed as normal to her as any other line of work. And when rock ’n’ roll came along in the late ’50s, Kaye naturally made the transition, where other women, for reasons of their own, decided to leave the business or stick purely with jazz.

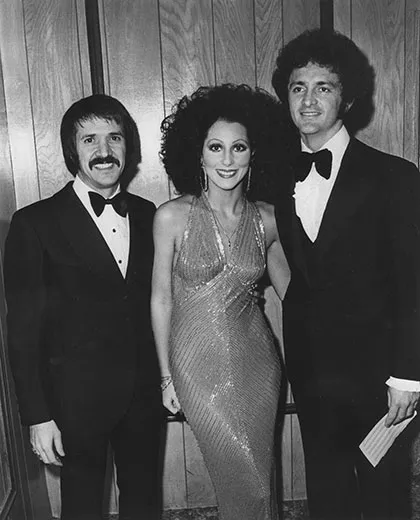

Over the years, Kaye had more than held her own while moving up the studio ladder, too, and she was not at all shy about defending her turf. Whenever some wise-guy male musician would comment, “Hey, that’s pretty good for a woman,” she would immediately counter his backhanded compliment with, “Well, that’s pretty good for a man, too.” That was also a big part of why Sonny Bono liked having her on his sessions: She was quick and she was creative.

***

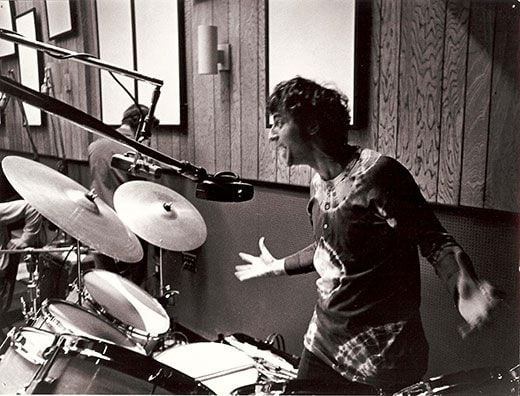

As Kaye carefully listened one day in the studio as she and her fellow musicians ran through “The Beat Goes On” several times in order to try to make sense out of it, she knew that she was going to have to come up with something inventive. In her opinion, the droning, one-chord tune was a real dog; it just lay there. Playing around with several bass lines on her acoustic guitar, she then came upon a particular pattern that had some real hop to it. Dum-dum-dum-da-dum-dum-da-dum-dum.

Bono immediately stopped the session.

“That’s it, Carol,” he whooped. “What’s that line you’re playing?”

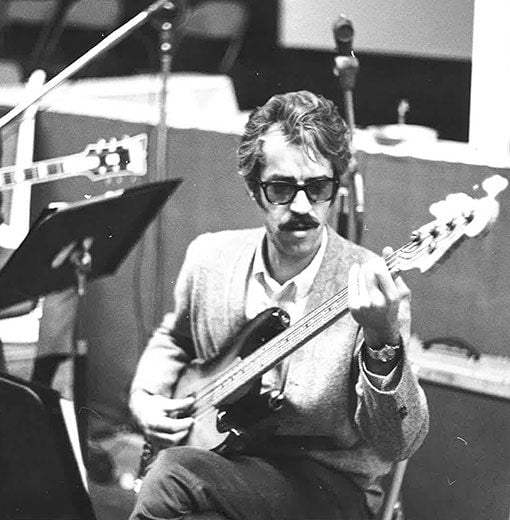

Maybe he couldn’t really play an instrument himself, least of all the bass, but Bono instinctively knew a signature lick when he heard one. And Kaye had just come up with an all-timer. As she dutifully played her creation once more for the producer, Bono had Bob West, the electric bass player on the date, learn it on the spot. Kaye and West then proceeded to play the simple yet transformative line in unison on the final recording, turning a previously lifeless production into a surefire hit.

Entering the charts in January 1967, “The Beat Goes On” made it all the way to number six, giving Sonny & Cher their biggest Top 40 showing in almost two years. Stepping in as the song’s de facto arranger, the independent-thinking Carol Kaye had just saved Bono’s composition, and likely Sonny & Cher’s tepid recording career, from an almost certain demise.

But the beat also went on for scores of others trying to gain a measure of their own fame and fortune in the high-flying, competitive Top 40 marketplace of the mid-’60s. There was always another Sonny Bono or Jan and Dean or Roger McGuinn waiting in the wings someplace, anonymously dreaming the same fevered dream. The “kids’ ” music that label executives like Mitch Miller at Columbia had once derisively dismissed as a passing fad had now become firmly entrenched as the biggest-selling genre of them all. Rock ’n’ roll had gone mainstream. Which gave the Wrecking Crew players more studio work than they knew what to do with. For Kaye, it meant a grand total of more than 10,000 sessions.

From The Wrecking Crew by Kent Hartman. Copyright © 2012 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.