The History of Snowshoe Racing

For some athletes, there is no such thing as cabin fever, as the snowy outdoors provides yet another outlet for competitive sport

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/snowshoe-racing-2010-La-Ciaspolada-race-631.jpg)

Laurie Lambert is a runner, always has been, it seems. So when she was snowed in at her remote cabin in New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains nine years ago, she strapped on a tiny pair of children’s snowshoes and went out for a long run.

“It was awesome,” she remembers. “I was like, wow, I think I could make a sport out of this. Little did I know it was already a sport.”

As Lambert soon found out, snowshoe racing has become an increasingly popular sport in the United States and abroad, where last January more than 5,000 people competed in the 37th running of La Ciaspolada Snowshoe Race in the Italian Dolomites, a ten-kilometer event won by a former Olympic marathoner from New Zealand. In the United States, this season began with a race in Truckee, California, in December, and ends in March with the National Snowshoe Championships in Cable, Wisconsin.

Mark Elmore, the sports director for the United States Snowshoe Association, was a die-hard endurance runner who started racing on snowshoes in 1989. “It added variety to the winter season,” he says. “And I really liked the people. There was a different mentality than road racing where you’re just trying to beat the other competitors. In snowshoeing, you’re racing against the course and the snow conditions. You’re competing against yourself a little more.”

Most of the enthusiasts are like Lambert – runners, cyclists or triathletes looking for a new challenge and another way to get outside and raise their heart rates. “It’s so much fun,” she says. “It’s fantastic exercise. I’ve run marathons and done all kinds of crazy things and it’s the best workout I’ve ever done.”

The rise of snowshoe racing parallels the rise in popularity of snowshoeing. According to the Outdoor Industry Foundation, 3.4 million Americans traipsed through the winter wonderland on snowshoes in 2009, a 17.4 percent increase over 2008.

Divining when the snowshoe was invented is difficult because the ancient materials used to make them were perishable, but the consensus is they developed in Central Asia about 4000 B.C. Elmore says snowshoes may have facilitated crossing the Bering land bridge. They appear to have developed independently in both North America and Europe, with European snowshoes longer and narrower).

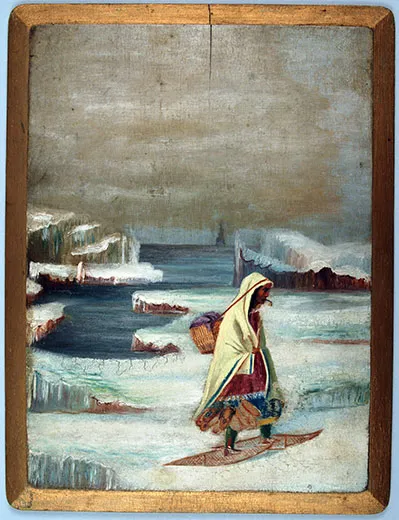

The traditional webbed snowshoe used in racing was created by American Indians. Explorer Samuel de Champlain wrote in his memoirs of them using “a kind of snowshoe that are two to three times larger than those in France, that they tie to their feet, and thus go on the snow, without sinking into it, otherwise they would not be able to hunt or go from one location to the other.”

In the 1830s, painter George Catlin depicted Indian use of snowshoes in paintings such as Snowshoe Dance at the First Snowfall and Buffalo Chase in Winter, Indians on Snowshoes. Tribes each developed their own shoe, differing in shape and size. The bear paw, an oval design, was short and wide and favored in forested areas. The Ojibwa shoe resembled a canoe, and its double toe helped the tribes of Manitoba cross diverse country. The Michigan, a snowhsoe credited to the Huron tribe, featured a long tail and was shaped like a tennis racket, allowing hunters to carry heavy loads of elk and buffalo.

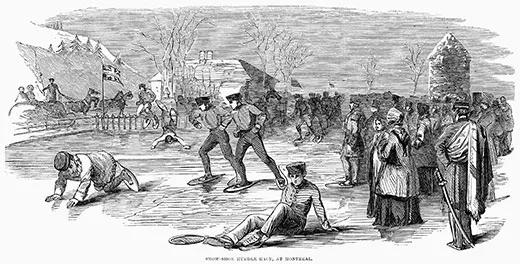

The forerunners of snowshoe-racing associations were the snowshoe recreation clubs that began in Canada and the northeastern United States in the late 18th century. Outings in places including Montreal and northern New England towns were major events. To make the shoes easier to maneuver, the clubs shortened the long teardrop trapper and tracker’s snowshoe to about 40 inches.

Beginning in the 1970s, designers of racing snowshoes trimmed them and lightened them even more, using the type of aluminum alloy used in spacecraft. The newest models now weigh as little as 16 ounces a shoe. “The modern racing snowshoe is a marvel that allows you to cover ground on soft snow so much easier,” Elmore says. “If you can walk or jog, you can run on snowshoes. There aren’t any specific skills you have to learn.”

In Europe, where snowshoe racing has been growing for decades, the Snowshoe Cup features six races in five countries from January to March. Organized racing in Europe began earlier than in the United States with the first running of La Ciaspolada in 1972.

In the United States, races are held in most regions of the country, including the Snow or No Snow Race in Flagstaff, Arizona. The courses vary as widely as the snow conditions. Elmore says there’s usually powder out West, where some events require organizers break the trail. In the East, snow conditions tend to be icier and thus the courses tend to follow packed trails, which are faster and require less effort than breaking a trail in powder. Distances are often ten kilometers, but there are also half marathons and even marathons, where the winners post times in the neighborhood of four and a half hours. While records exist for various races, the differences in course conditions make them hard to compare. Big prizes used to be awarded to race winners, but those have faded with the recent economic crises.

Chary Griffin, 62, who lives in Cazenovia, southeast of Syracuse, New York, trains six miles every other day on a packed trail. She stows a box of racing snowshoes in her car to lend to friends so they can come along. Anyone, she says, can run in snowshoes. “It’s my winter sport,” she says. “I’m serious about getting other people hooked into this.”

Scott Gall, 36, of Cedar Falls, Iowa, moved to Wyoming after running distances at Wabash College and fell into snowshoe racing. He found it wasn’t as easy as strapping on snowshoes and taking a jog. “The first ten minutes are killer no matter what you’ve been doing,” he says. “You just have to adjust to it. It’s a lot of work to have things strapped to your feet. But once you’re ten minutes into it, your heart rate settles down.”

Lambert, Griffin and Gall clearly enjoy the competition against others and themselves. (Gall finished second in last year’s national championship.) But they seem to enjoy, just as much, if not more, the bracing air, the diverse landscape, and the joy of being outdoors when most others are huddled inside. As Gall notes, it’s warmer in winter snowshoeing in the woods than running on the roads.

“Going tromping through the woods on a full moon night is awesome,” he says. “It’s not just the competition. It’s getting outside in the fresh air and doing something fun. Somewhere along the way, they told adults you can’t enjoy it when the snow flies.”

Lambert regularly trains above 9,500 feet in New Mexico, below the tree line. But she recalls the stunning beauty of a world cup race she participated in in Austria. “That was way above the trees on the Dachstein Glacier. It felt like we were visitors on some other planet,” she says. “Otherworldly.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)