The History of the Flapper, Part 2: Makeup Makes a Bold Entrance

It’s the birth of the modern cosmetics business as young women look for beauty enhancers in a tube or jar

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130207102026lipstick-stencil_470.jpg)

Let us take a look at the young person as she strolls across the lawn of her parents’ suburban home, having just put the car away after driving sixty miles in two hours. She is, for one thing, a very pretty girl. Beauty is the fashion in 1925. She is frankly, heavily made up, not to imitate nature, but for an altogether artificial effect—pallor mortis, poisonously scarlet lips, richly ringed eyes—the latter looking not so much debauched (which is the intention) as diabetic. Her walk duplicates the swagger supposed by innocent America to go with the female half of a Paris Apache dance.

Flapper Jane by Bruce Bliven

The New Republic

September 9, 1925

In the decades before the Roaring Twenties, nice girls didn’t wear makeup. But that changed when flappers began applying cosmetics that were meant to be noticed, a reaction to the subdued and feminine pre-war Victorian attitudes and styles typified by the classic Gibson girl.

Before the 1920s, makeup was a real pain to put on. It’s no wonder women kept it to a minimum. The tubes, brushes and compacts we take for granted today hadn’t yet been invented. Innovations in cosmetics in the ’20s made it much easier for women to experiment with new looks. And with the increasing popularity of movies, women could mimic the stars—like Joan Crawford, Mae Murray and Clara Bow, an American actress who epitomized the flapper’s spitfire attitude and heavily made-up appearance.

Let’s start with rouge—today we call it blush. Before the ’20s, it was messy to use and associated with promiscuous women. But with the introduction of the compact case, rouge became transportable, socially acceptable and easy to apply. The red—or sometimes orange—makeup was applied in circles on the cheeks, as opposed to dabbed along the cheekbones as it is today. And, if you were particularly fashionable, you applied it over a suntan, a trend popularized by Coco Chanel’s sunbathing mishap.

And lipstick! With the invention of the metal, retractable tube in 1915, lipstick application was forever revolutionized. You could carry the tube with you and touch up often, even at the dinner table, which was now tolerated. Metal lip tracers and stencils ensured flawless application that emphasized the lip line. The most popular look was the heart-shaped “cupid’s bow.” On the upper lip, lipstick rose above the lip line in the shape of a cupid’s bow. On the lower lip, it was applied in an exaggerated manner. On the sides, the color stopped short of the natural lip line.

For even more foolproof application, in 1926, cosmetics manufacturer Helena Rubinstein released Cupids Bow, which it marketed as a “self-shaping lipstick that forms a perfect cupid’s bow as you apply it.” Red was the standard color, and sometimes it was cherry flavored. The 1920s stage and screen actress Mae Murray, the subject of a new biography, The Girl With the Bee Stung Lips, exemplified the look with her distinctive crimson lips.

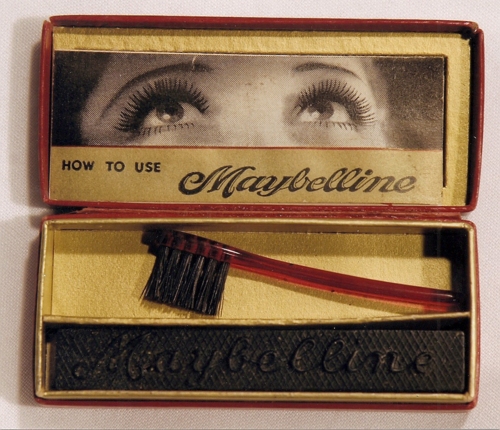

Maybelline mascara featuring actress Mildred Davis’ eyes, 1920s.

As for the eyes, women lined them with dark, smudged kohl. They plucked their eyebrows to form a thin line, if not entirely, and then drew them back in, quite the opposite of 1980s Brooke Shields. Mascara, still working out the kinks, came in cake, wax or liquid form. The Maybelline cake mascara had instructions, a brush and a photo of actress Mildred Davis’ eyes. Since the brush hadn’t evolved into the circular wand we have today, women used the Kurlash eyelash curler, invented by William Beldue in 1923, for a more dramatic effect.

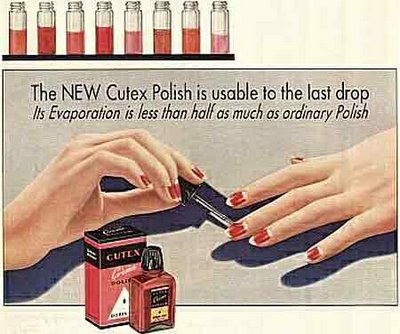

Nail lacquer took off in the 1920s when French makeup artist Michelle Ménard partnered with the Charles Revson company, Revlon, as we know it today. Inspired by the enamels used to paint cars, Ménard had wondered if something similar could be applied to fingernails. They established a factory, began producing nail polish as their first product, and officially founded the Revlon Company in 1932. The brands Max Factor and Cutex also introduced polishes throughout the 1920s. The “moon manicure” was in vogue: Women kept their nails long and painted only the middle of each nail, leaving the crescent tip unpolished.

A confluence of events led women to become more receptive to powdering their noses. First, the invention of safer cosmetics throughout the decade (since applying lead to your face wasn’t the best idea!) was key, and much of what we see in drugstores and at makeup counters today originated during the 1920s. Women were competing for attention, and for jobs, after men returned from World War I, and to that end, they wore makeup to be noticed. The idea of feminine beauty was overhauled. As the conservative attitudes of previous decades were abandoned, a liberating boldness came to represent the modern woman.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)