The History of the Flapper, Part 5: Who Was Behind the Fashions?

Sears styles sprung from the ideas of European artists and couturiers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130412101018Where_theres_smoke_theres_fire_by_Russell_Patterson_crop_470.jpg)

Have a look at the paintings of Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger and other Cubist painters whose work included hard, geometric forms and visible lines. As these artists were working in their studios, fashion designers, particularly those in France, were taking cues from their paintings. With la garçonne (the flapper, in French) in mind, the designers created fashions with the clean lines and angular forms we now associate with the 1920s-and with Cubism.

The styles we’ve come to connect with Louise Brooks, Norma Talmadge, Colleen Moore and other American actresses on the silver screen in the Jazz Age can be traced back to Europe, and more specifically, a few important designers.

- Jean Patou, known for inventing knit swimwear and women’s tennis clothes, and for promoting sportswear in general (as well as creating the first suntan oil), helped shape the 1920s silhouette. Later in the decade, he revolutionized hemlines once again by dropping them from the knee to the ankle.

- Elsa Schiaparelli’s career built momentum in the ’20s with a focus mostly on knitwear and sportswear (her Surrealism-influenced garments like the lobster dress and shoe hat came later, in the 1930s).

- Coco Chanel and her jersey knits, little back dress and smart suits, all with clean, no-nonsense lines, arrived stateside along with Chanel No. 5 perfume and a desire for a sun-kissed complexion in the early 1920s.

- Madeleine Vionnet made an impression with the bias-cut garment, or a garment made using fabric cut against the grain so that it skimmed the wearer’s body in a way that showed her shape more naturally. Vionnet’s asymmetrical handkerchief dress also became a classic look from that time.

- Jeanne Lanvin, who started off making children’s clothing, made a name for herself when her wealthy patrons began requesting their own versions. Detailed beading and intricate trim became signatures of her designs.

As these designers were breaking new ground (and for some, that began in the 1910s), their looks slowly permeated mainstream culture and made their way across the pond. One of the best ways to see how these couturiers’ pieces translated into clothing with mass appeal is to look at a Sears catalog from the 1920s, which was distributed to millions of families across the United States. As Stella Blum explained in Everyday Fashions of the Twenties:

. . . mail-order fashions began to fall behind those of Paris and by 1930 the lag increased to about two years. Late and somewhat diluted, the style of the period nevertheless touched even the cheapest wearing apparel. The art movements in Paris and the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs of 1925 managed eventually to make their influence felt on the farms of Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas, and in the ghettos of the large cities.

Ordinary Parisians were almost completely over wearing the knee-length, dropped-waisted dresses by the mid- to late 1920s, but in the United States, the style was increasing in popularity. In Flapper Jane, an article in the September 9, 1925, issue of the New Republic, Bruce Bliven wrote:

These which I have described are Jane’s clothes, but they are not merely a flapper uniform. They are The Style, Summer of 1925 Eastern Seaboard. These things and none other are being worn by all of Jane’s sisters and her cousins and her aunts. They are being worn by ladies who are three times Jane’s age, and look ten years older; by those twice her age who look a hundred years older.

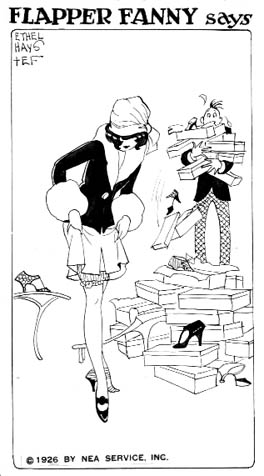

The flapper look was ubiquitous enough to make its way into illustrations and comics. The comic strip “Flapper Fanny Says” tracked the trials and tribulations of the eternally young and somewhat androgynously stylish Fanny. The invention of cartoonist Ethel Hays in 1924, the strip remained in print into the 1940s under different artists.

Around that time, John Held Jr.’s drawings of long-legged, slim-necked, bobbed-haired, cigarette-smoking flappers were making the covers of Life and the New Yorker. His vibrant illustrations, along with those of Russell Patterson and Ralph Barton, captured the exuberant lifestyle–and clothing style–of the time.

Looking back, we can now see how art inspired the decade’s fashion trends and how those fashions fueled a lifestyle. That, in turn, came just about full circle to be reflected in yet another form of visual representation—illustrated depictions of the freewheeling flapper culture—that kept the momentum of the decade going.

Read Parts I, II, III and IV of our History of the Flapper series for more great back story on the fashion icon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)