The Many, Many Designs of the Sewing Machine

Rioting tailors, destitute inventors and the court system all got involved in one of the 19th century’s biggest innovations

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131016125035sewing-machine-470.jpg)

In the early years of the 19th century, the invention of the sewing machine was all but inevitable. Factories were filling with seamstresses and tailors, and savvy inventors and entrepreneurs around the world saw the stitching on the trousers. There were an incredible number of machine designs, patents, and — some things never change — patent lawsuits.

![]()

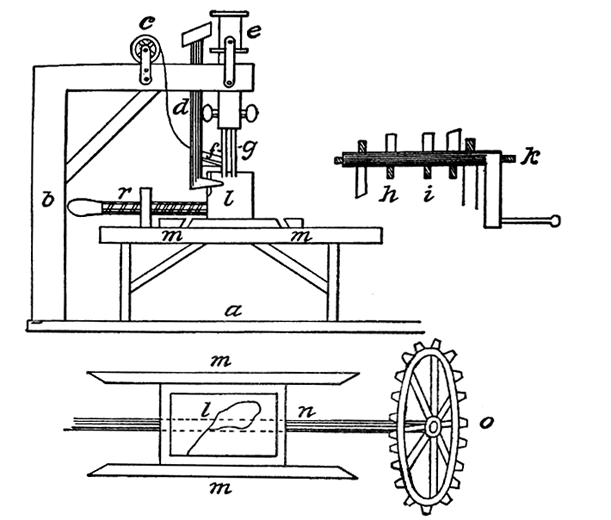

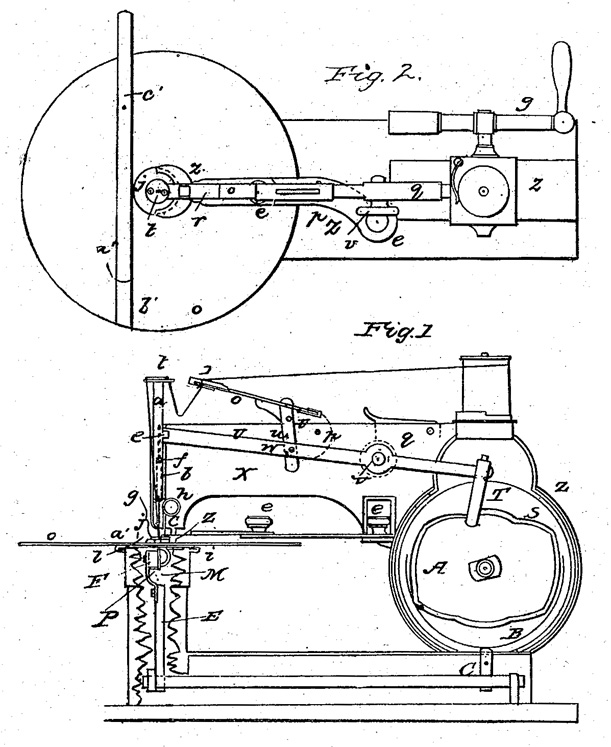

Thomas Saint’s 1790 drawing for a leather sewing machine

Here’s a brief overview describing some of the greatest hits (and misses) to illustrate the heady mix of industrialism, politics and revolutionary rhetoric that surrounded the development of the sewing machine.

The design of the first sewing machine actually dates back to the late 18th century, when an English cabinetmaker by the name of Thomas Saint drew up plans for a machine that could stitch leather. He patented the design as “An Entire New Method of Making and Completing Shoes, Boots, Spatterdashes, Clogs, and Other Articles, by Means of Tools and Machines also Invented by Me for that Purpose, and of Certain Compositions of the Nature of Japan or Varnish, which will be very advantageous in many useful Appliances.”

The rather prolix title partly explains why the patented was eventually lost – it was filed under apparel. It’s not known if Saint actually built any of his designs before he died, but a functioning replica was built 84 years later by William Newton Wilson. Though it’s not exactly practical, the hand-cranked machine worked after a few slight modifications.

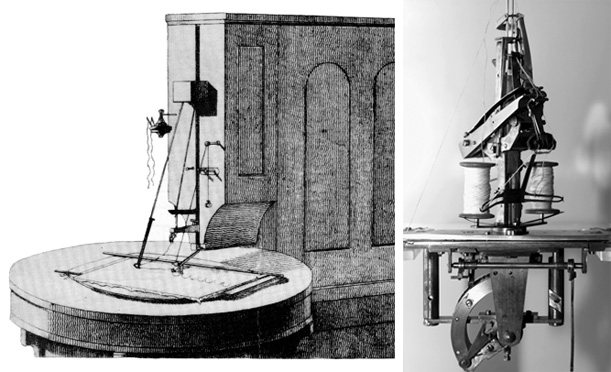

left: Madersperger’s 1814 design, illustration from a circa 1816 pamphlet by the inventor. right: a later Madersperger prototype, possibly his last

In the first half of the 19th century there was an explosion of sewing machine patents – and patent infringement cases. In 1814, Viennese tailor Josef Madersperger was granted a patent on a design for a sewing machine he had been developing for nearly a decade. Madersperger built several machines. The first was apparently designed to sew only straight lines while later machines may have been specially made to create embroidery, capable of stitching small circles and ovals. The designs were well received by the Viennese public but the inventor wasn’t happy with the reliability of his machines and he never made one commercially available. Madersperger would spend the rest of his life trying to perfect his design, a pursuit that would exhaust his last penny and send him to the poorhouse – literally; he died in a poorhouse.

In France, the first mechanical sewing machine was patented in 1830 by tailor Barthélemy Thimonnier, whose machine used a hooked or barbed needle to produce a chain stitch. Unlike his predecessors, Thimonnier actually put his machine into production and was awarded a contract to produce uniforms for the French army. Unfortunately, also like his predecessors, he met with disaster. A mob of torch-waving tailors worried about losing their livelihood stormed his factory, destroying all 80 of his machines. Thimonnier narrowly escaped, picked himself up by his mechanically-assembled bootstraps, and designed an even better machine. The unruly tailors struck again, destroying every machine save one, with which Thimonnier was able to escape. He attempted to start over in England but his efforts were for naught. In 185,7 Barthélemy Thimonnier also died in a poorhouse.

So things didn’t turn out well for three of the more prominent early enablers of prêt-à-porter apparel in Europe. But what was going on across the pond? What was going on in that upstart nation of go-getters, problem solvers, and destiny manifesters? Well that’s where things get really interesting.

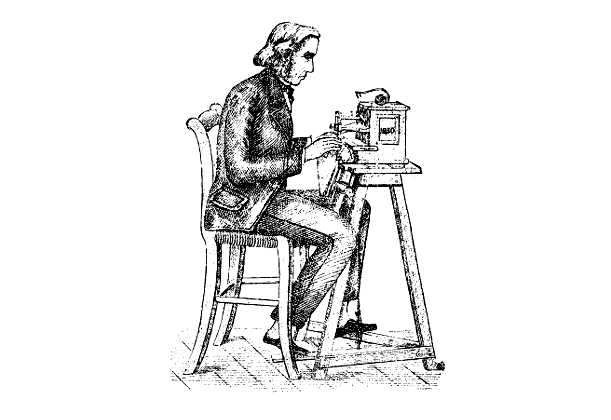

Walter Hunt was a prolific inventor and was described by Smithsonian curator Grace Rogers Cooper in her 1968 paper, The Invention of the Sewing Machine, as a “Yankee mechanical genius.” He designed a nail-making machine, a plow, a bullet, a bicycle and the safety pin, which was designed in three hours to settle a $15 debt. A clever man who was attuned to the tenor of the times, Hunt understood the value of a machine that could sew and set out to built one in 1832. He designed a simple machine that used two needles, one with an eye in its point, to produce a straight “lock stitch” seam and encouraged his daughter to open a business producing corsets. But Hunt had second thoughts. He was dismayed by the prospect that his invention might put seamstresses and tailors out of work, so he abandoned his machine in 1838 having never filed for a patent. But that same year, a poor tailor’s apprentice in Boston named Elias Howe began working a very similar idea.

After failing to build a machine that reproduced his wife’s hand motions, Howe scrapped the design and started again; this time, he inadvertently invented a hand-cranked machine almost identical to Hunt’s. He earned a patent for his design in 1846 and staged a man-vs-machine challenge, beating five seamstresses with work that was faster and in every way superior. Yet the machine was still seen as somewhat scandalous, and Howe failed to attract any buyers or investors. Undeterred, he continued to improve his machine.

A series of unfortunate business decisions, treacherous partners, and a trip oversees left Howe destitute in London. What’s more, his wife’s health was failing and he had no means to get back to her in America. He was very close to suffering the same fate that befell Thimonnier, becoming just another dead inventor in the poorhouse. After pawning his machines and patent papers to pay for steerage back to the States in 1849, the distraught Howe returned to his wife just in time to stand by her bedside as she died. Adding insult to injury, he learned that the sewing machine had proliferated in his absence – some designs were almost copies of his original invention while others were based on ideas he patented in 1846. Howe had received no royalties for any of the machines- royalties that likely could have saved his wife’s life. Destitute and alone, he pursued his infringers fiercely, with the single-minded dedication of a bitter man with nothing left to lose. Many paid him his due immediately but others fought Howe in court. He won every single case.

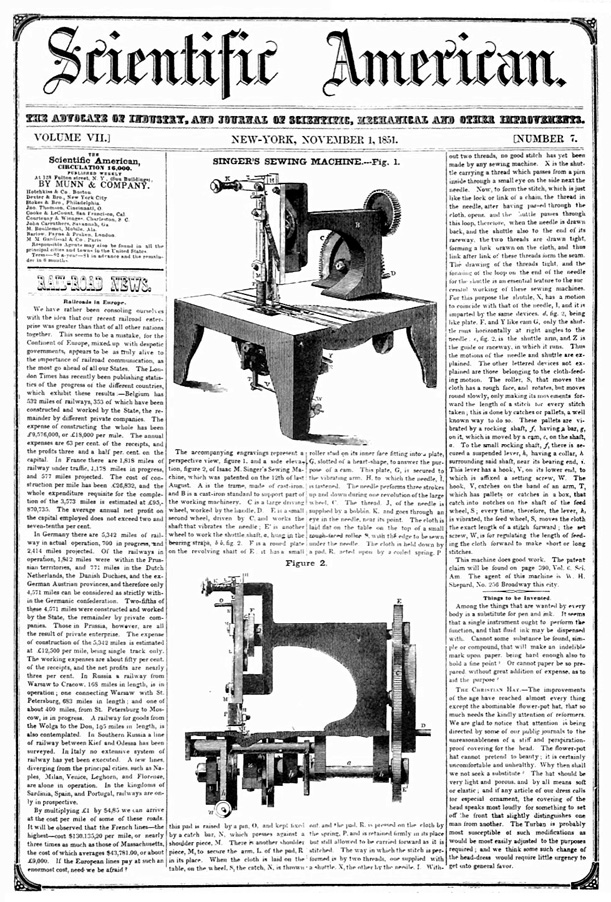

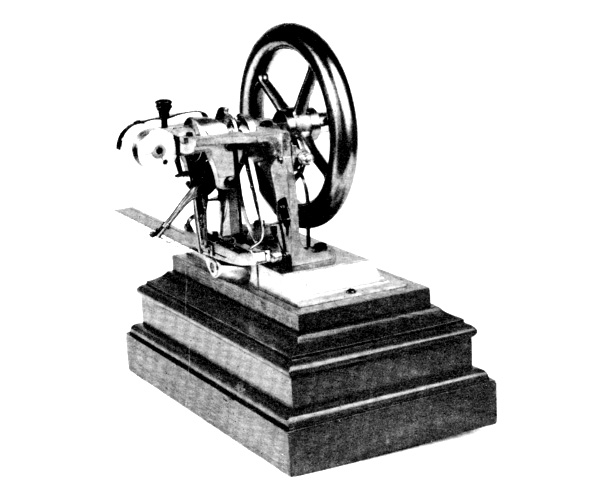

Singer’s machine was featured in the November 1, 1851 issue of Scientific American

Soon after the conclusion of his last court case, Howe was approached with a unique offer. An machinist by the name of Isaac Singer had invented his own sewing machine that was different in almost every way than Howe’s; every way except one – its eye-pointed needle. That little needle cost Singer thousands of dollars in royalties, all paid to Howe, but inspired the country’s first patent pool. Singer gathered together seven manufactures –all of whom had likely lost to Howe in court– to share their patents. They needed Howe’s patents as well and agreed to all his terms: every single manufacturer in the United States would pay Howe $25 for every machine sold. Eventually, the royalty was reduced to $5 but it was still enough to ensure that by the time Elias Howe died in 1867, he was a very, very rich man, having earned millions from patent rights and royalties. Singer didn’t do too bad for himself either. He had a penchant for promotion and, according to American Science and Invention earned the dubious recognition of becoming the first man to spend more than $1 million dollars a year on advertising. It worked though. The world hardly remembers Elias Howe, Walter Hunt, Barthélemy Thimonnier, Josef Madersperger, and Thomas Saint, but Singer is practically synonymous with sewing machine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)