The History of the Minivan

The iconic car changed the way families drove

![]()

If the minivan were a person, now in its mid-30s, it might be shopping for a minivan of its own to haul the kids to soccer practice and take family vacations to Myrtle Beach. But it also might stare at itself in the mirror, check for a receding hairline, and ask some serious question like “How did I get here?” and “What am I doing with my life?”

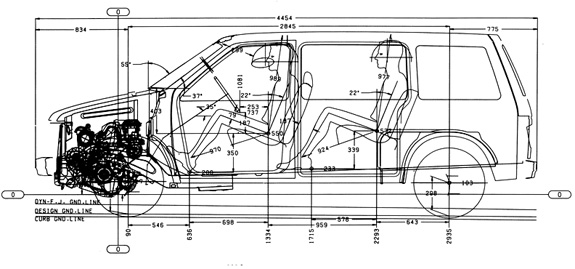

When Chrysler introduced the Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager in 1983, the company was on the brink of collapse. It was a situation that sounds like it could have come from yesterday’s headlines: the company was nearly bankrupt and surviving off a $1.5 billion loan from Uncle Sam. At the time, Lee Iacocca and Hal Sperlich were heading up Chrysler. Both men had worked on the 1963 Mustang and both had been ignominiously fired from Ford. Sperlich’s dismissal resulted, in part, from his constant exhortations to Henry Ford II to move forward with something Sperlich was calling the “mini-max” – a smaller version of Ford’s popular Econoline, named for minimum exterior, maximum interior. Market research had determined that for such a veheicle to be a success, it needed three critical elements: the floor had to be kept low enough for women to comfortably drive it, it must be small enough to fit in a garage, and the engine had to be far enough from the driver to provide “crush space” in the event of an accident. Ford dismissed the idea but by the time Sperlich ended up at Chrysler he would, with Iacocca’s help, get the struggling auto manufacturer to put nearly half of that $1.5 billion toward the development of a truly game-changing vehicle.

In the early 1970s, a team of 100 Chrysler engineers had been collaborating on a project that was being referred to in-house as the “garageable van.” The name pretty much describes what they were going for: a spacious family vehicle that could fit in a standard garage. Money was obviously a huge problem for Chrysler, and due to the massive development costs tied to creating an entirely new model, the project was never approved. The failing company was afraid to be the first to market with an untested vehicle. The thought was, if there was a market for these miniature vans, someone else –GM and Ford, namely– would be producing them. But Chrysler needed to take a risk. And in 1980 Iacocca forced the company to allocate the necessary funds and, under the guidance of Sperlich, the design team moved forward.

Sperlich’s background was in product planning. This meant that it was his job to find the right balance of power, speed, space, and cost that’s essential to a successful vehicle. He envisioned a van that could be built on a car chassis. Something more than a station wagon but less than a full size van. Luckily, Chrysler had just the thing. The minivan was built on a modified version of the recently introduced K-Car chassis that was the basis for most of Chrysler’s cars at the time. The front-wheel-drive K-Platform let Chrysler keep the overall size down and maintain an expansive, open interior – qualities that previous research proved to be essential. The final height of the first minivan would be just 64 inches – 15 inches lower than the smallest van on the market at the time. The overall form of the new vehicle was called a “one-box” design, as opposite to the three-box design –hood, cabin, trunk– of standard cars. The other distinguishing features of the new minivan were its car-like features – notably including power windows, comfortable interiors, a nice dashboard, and front-wheel drive. These also explain the appeal of the vehicle. Not only did it fit in a garage like a car, but it actually drove like a car, while also providing plenty of room for the kids and luggage and giving mom a nice, high view of the road.

But what explains the minivan’s most iconic feature – the single, sliding door? That, it seems, was a bit of value engineering that just stuck. From early in the design process, it was determined that the new vehicle would be targeted toward families. The sliding door made it easy to for people to quickly enter or exit the vehicle and, with its lack of hinges, the sliding door was seen as a safer option for children. Initially, the door was only installed on one side to save on manufacturing costs during the cash-strapped company’s tentative foray into an entirely new market. When the van debuted, no one complained. So why mess with success?

Although Chrysler may have been the first to market with the minivan, but they didn’t invent the idea of the miniature van. Small vans and large cars were in production in Europe and Asia since the 1950s, such as the idiosyncratic Stout Scarab, the iconic Volkswagen bus, and the DKW Schnellaster (above image), a 1949 FWD vehicle that has been called “The Mother of all modern minivans.”

But in 1983 when Chrysler introduced the Voyager and the Caravan –named for its origins, “car and van” – they almost literally created the mold for the minivan. Not only that, but they created an entirely new market. The vehicle wasn’t sexy and it wasn’t even that great of a car, but it was an immediate success. Road and Track called it “a straightforward, honest vehicle. Honest in the sense that is is designed to be utilitarian. Yet it is clean and pleasant to look at. It doesn’t pretend to be what it’s not.” Car and Driver were even more effusive, reporting that the new models from Chrysler were “a sparkling example of the kind of thinking that will power Detroit out of its rut and may very well serve to accelerate Chrysler’s drive back to the big time.” Indeed, Chrysler couldn’t make them fast enough, and drivers waited weeks for the minivan. It was a practical car that the baby boomers needed. The success of the minivan helped bring the company back from the edge of bankruptcy. As the minivan turns 30, its story seems more relevant now than ever. Hopefully, history will repeat itself and Detroit will once again start producing some exciting, game-changing automobiles.

Sources:

Paul Ingassia, Engines of Change: A History of the American Dream in Fifteen Cars (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012); Michael L. Berger, The Automobile in American History and Culture: A Reference Guide (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2001); ”The Caravan/Voyager Development Story,” Allpar; United States International Trade Commission, Minivans from Japan (1992); Paul Niedermeyer, “The Mother of All Modern Minivans,” The Truth About Cars(March 29, 2010); Charles K. Hyde, Riding the Roller Coaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)