The Museum of Jurassic Technology

A throwback to the private museums of earlier centuries, this Los Angeles spot has a true hodgepodge of natural history artifacts

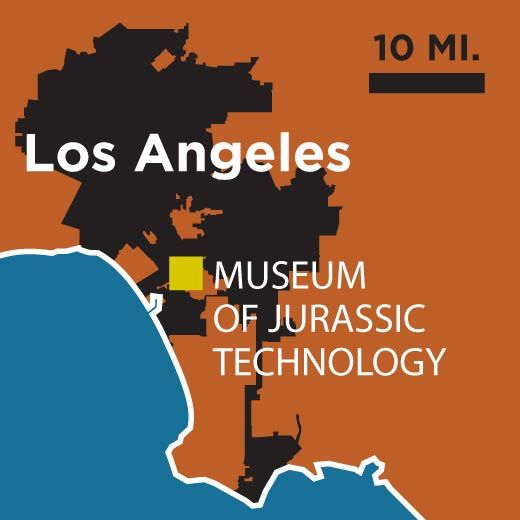

To find the Museum of Jurassic Technology, you navigate the sidewalks of Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles, ring a brass buzzer at a facade that evokes a Roman mausoleum and enter a dark, hushed antechamber filled with antique-looking display cases, trinkets and taxidermic animals. After making a suggested $5 “donation,” you are ushered into a maze of corridors containing softly lit exhibits. There are a European mole skeleton, “extinct French moths” and glittering gems, a study of the stink ant of Cameroon and a ghostly South American bat, complete with extended text by 19th-century scientists. The sounds of chirping crickets and cascading water follow your steps. Opera arias waft from one chamber. Telephone receivers at listening stations offer recorded narration about the exhibits. Wooden cabinets contain holograms that can be viewed through special prisms and other viewing devices, revealing, for example, robed figures at the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis, or a man growling like an animal in front of a gray fox’s head.

The Jurassic Technology Museum is a witty, self-conscious homage to private museums of yore, such as the 16th-century Ashmolean at Oxford, where objects from science, nature and art were displayed for the “rational amusement” of scholars, and the 19th-century Philadelphia Museum, with its bird skeletons and mastodon bones. The phrase “Jurassic technology” is not meant literally. Instead, it evokes an era when natural history was only barely charted by science, and museums were closer to Renaissance cabinets of curiosity.

It is the brainchild of David Wilson, a 65-year-old Los Angeles native who studied science at Kalamazoo College, in Michigan, and filmmaking at the California Institute of the Arts, in Valencia. “I grew up loving museums,” says Wilson, whose scholarly demeanor gives him the air of a Victorian don. “My earliest memory is of just being ecstatic in them. When I was older, I tried making science films, but then it occurred to me that I really wanted to have a museum—not work for a museum, but have a museum.” In 1988, he leased a near-derelict building and began setting up exhibits with his wife, Diana Wilson. “We thought there wasn’t a prayer that we’d last here,” he recalls. “The place was supposed to be condemned!” But the museum slowly expanded to take up the whole building, which Wilson bought in 1999. Today, it attracts over 23,000 visitors a year from around the world.

Among the medical curios are ant eggs, thought in the Middle Ages to cure “love-sickness,” and duck’s breath captured in a test tube, once believed to cure thrush. Some exhibits have a Coney Island air, such as the microscopic sculptures of Napoleon and Pope John Paul II; each fits in the eye of a needle. Others are eerily beautiful. Stereo Floral Radiographs—X-rays of flowers showing their “deep anatomy”—can be viewed in 3-D with stereograph glasses to a clamorous arrangement by Estonian composer Arvo Part.

Near the exit, I read about a “theory of forgetting,” then turned a corner to find a glass panel that revealed a madeleine and a 19th-century tea cup; I pressed a brass button, and air puffed out of a brass tube, carrying with it (one was assured) the scent of the very pastry that launched Marcel Proust’s immortal meditation, Remembrance of Things Past. I wasn’t entirely sure what it all meant, but as I stepped out onto Venice Boulevard, I knew without a doubt that the world is indeed filled with marvels.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)