The Nature of Glass

Prolific sculptor Dale Chihuly plants his vitreous visions in a Florida garden

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/chihuly-extra5.jpg)

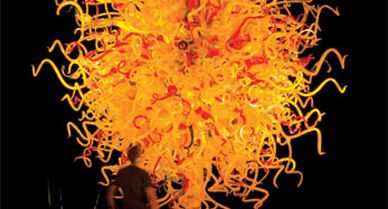

An encounter with Dale Chihuly's works is always a spectacular reminder that glass is not just something to see through or drink out of. His latest exhibition, at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Florida, features 15 installations, including a 26-foot tower made out of a half mile of neon tubing and an enormous sun made of a thousand individually-blown glass pieces.

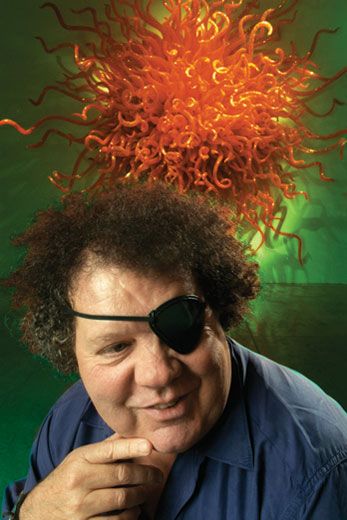

Chihuly, who started out as an interior designer in the 1960s, was the first American to apprentice at Venice's renowned Venini Glass Factory, in 1968. Upon his return to the United States, he helped elevate glass blowing from craft to art. In 1976, the Metropolitan Museum of Art bought three Chihuly vessels inspired by Navajo blankets, and he has been something of an art-world celebrity ever since. "He has personally pushed glass blowing farther than anyone ever imagined it could be pushed," Benjamin Moore, a glass artist who once worked for Chihuly, has said.

It is perhaps surprising that it took so long for Chihuly, 65, to begin putting his work in gardens. Years before his first major garden show, in 2001, he'd said he wanted his glass "to appear like it came from nature—so that if someone found it on a beach or in the forest, they might think it belonged there." And indeed, Mike Maunder, Fairchild's director, sees some Chihuly pieces as a "distillation of the tropical world." If Chihuly's art has borrowed from nature, nature has been paid back with interest, with proceeds from Chihuly's shows supporting Fairchild's conservation and education programs. After Chihuly's 2005-6 exhibition drew record numbers of visitors, the 83-acre botanic garden invited Chihuly for a return engagement. The current exhibition closes May 31.

Since the 1970s, when a car crash robbed Chihuly of vision in one eye and a subsequent injury damaged his shoulder, he has not blown his own glass but has directed the work of others at his studio, in Seattle; he currently employs about 100 people. Critics have called the work "vacant" and have scoffed at Chihuly's methods, with one writing last year, "When is an art factory just a factory?" Chihuly's supporters say the work remains transcendent, and counter that many revered artists—from Michelangelo onward—have had plenty of help.

For his part, Chihuly says he could never have created his more ambitious pieces working alone. And he once mused that while it might be "possible" to mount a large installation by himself, "the whole process would just be too slow for me." He is famously productive, with up to 50 exhibitions a year. At the moment, he says he's weighing offers from gardens from Honolulu to Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)