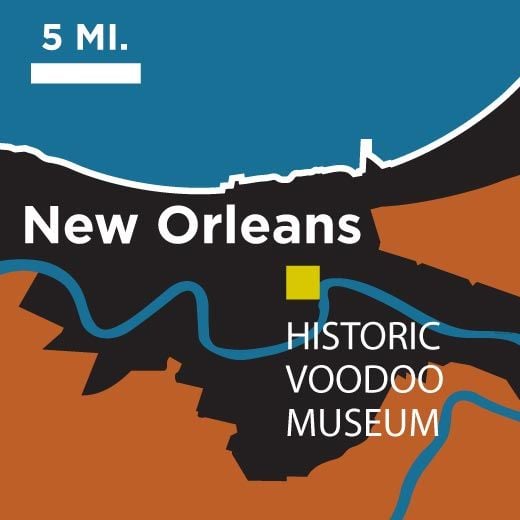

The New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum

Wooden masks, portraits and the occasional human skull mark the collections of this small museum near the French Quarter

Jerry Gandolfo didn’t flinch when a busload of eighth-grade girls began shrieking at the front desk. The owner of the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum simply assumed that John T. Martin, who calls himself a voodoo priest, was wearing his albino python around his neck as he took tickets. A few screams were par for the course.

Deeper in the museum it was uncomfortably warm, because the priest has a habit of turning down the air conditioning to accommodate his coldblooded companion. Not that Gandolfo minded: snakes are considered sacred voodoo spirits and this particular one, named Jolie Vert ( “Pretty Green,” although it is pale yellow), also furnishes the little bags of snake scales that sell for $1 in the gift shop, alongside dried chicken feet and blank-faced dolls made of Spanish moss.

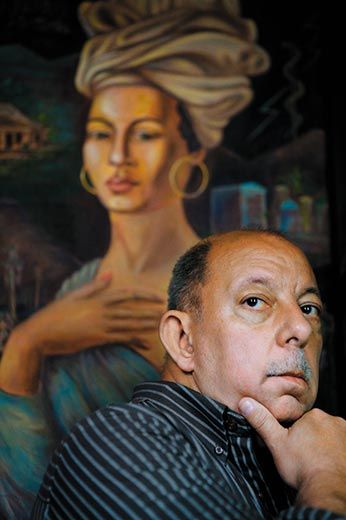

A former insurance company manager, Gandolfo, 58, is a caretaker, not voodoo witch doctor—in fact, he’s a practicing Catholic. Yet his weary eyes brighten when he talks about the history behind his small museum, a dim enclave in the French Quarter half a block off Bourbon Street that holds a musty jumble of wooden masks, portraits of famous priestesses, or “voodoo queens,” and here and there a human skull. Labels are few and far between, but the objects all relate to the centuries-old religion, which revolves around asking spirits and the dead to intercede in everyday affairs. “I try to explain and preserve the legacy of voodoo,” Gandolfo says.

Gandolfo comes from an old Creole family: his grandparents spoke French, lived near the French Quarter and rarely ventured beyond Canal Street into the “American” part of New Orleans. Gandolfo grew up fully aware that some people swept red brick dust across their doorsteps each morning to ward off hexes and that love potions were still sold in local drugstores. True, his own family’s lore touched on the shadowy religion: his French ancestors, the story went, were living in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) when slave revolts convulsed their sugar plantation around 1791. To save Gandolfo’s kinfolk, a loyal slave hid them in barrels and smuggled them to New Orleans. The slave, it turned out, was a voodoo queen.

But it wasn’t until Gandolfo reached adulthood that he learned that countless Creole families told versions of the same story. Still, he says, “I don’t think I even knew how to spell voodoo.”

That changed in 1972, when Gandolfo’s older brother Charles, an artist and hairdresser, wanted a more stable career. “So I said, ‘How about a voodoo museum?’” Gandolfo recalls. Charles—soon to be known as “Voodoo Charlie”—set about gathering a hodgepodge of artifacts of varying authenticity: horse jaw rattles, strings of garlic, statues of the Virgin Mary, yards of Mardi Gras beads, alligator heads, a clay “govi” jar for storing souls, and the wooden kneeling board allegedly used by the greatest voodoo queen of all: New Orleans’ own Marie Laveau.

Charlie presided over the museum in a straw hat and an alligator tooth necklace, carrying a staff carved as a snake. “At one point he made it known that he needed skulls, so people sold him skulls, no questions asked,” Gandolfo says. “Officially, they came from a medical school.”

Charlie busied himself with recreating raucous voodoo ceremonies on St. John’s Eve (June 23) and Halloween night, and sometimes, at private weddings, which typically were held inside the building and outside, in nearby Congo Square, and often involved snake dances and traditional, spirit-summoning drumming. Charlie “was responsible for the renaissance of voodoo in this city,” Gandolfo says. “He revitalized it from something you read in history books and brought it back to life again.” Meanwhile, Charlie’s more introverted brother researched the history of the religion, which spread from West Africa by means of slave ships. Eventually, Gandolfo learned how to spell voodoo—vudu, vodoun, vodou, vaudoux. It’s unclear how many New Orleanians practice voodoo today, but Gandolfo believes as much as 2 or 3 percent of the population, with the highest concentrations in the historically Creole Seventh Ward. The religion remains vibrant in Haiti.

Voodoo Charlie died of a heart attack in 2001, on Mardis Gras day: his memorial service, held in Congo Square, attracted hundreds of mourners, including voodoo queens in their trademark tignons, or head scarves. Gandolfo took over the museum from Charlie’s son in 2005. Then Hurricane Katrina hit and tourism ground to a halt: the museum, which charges between $5 and $7 admission, once welcomed some 120,000 visitors a year; now the number is closer to 12,000. Gandolfo, who is unmarried and has no children, is usually on hand to discuss voodoo history or to explain (in frighteningly precise terms) how to make a human “zombie” with poison extracted from a blowfish. (“Put it in the victim’s shoe, where it is absorbed through sweat glands, inducing a death-like catatonic state,” he says. Later, the person is fed an extract containing an antidote to it as well as powerful hallucinogens. Thus, the “zombie” appears to rise from the dead, stumbling around in a daze.)

“The museum is an entry point for people who are curious, who want to see what’s behind this stuff,” says Martha Ward, a University of New Orleans anthropologist who studies voodoo. “How do people think about voodoo? What objects do they use? Where do they come from? [The museum] is a very rich and deep place.”

The eighth graders—visiting from a rural Louisiana parish—filed through the rooms, sometimes pausing to consider candles flickering on the altars or to stare into the vacant eye sockets of skulls.

The braver girls hoisted Jolie Vert over their shoulders for pictures. (“My mom’s going to flip!”) Others scuttled for the door.

“Can we go now?” one student asked in a small voice.