The Patents Designed to Make Carving Your Pumpkin a Little Less Messy

A group of innovators set out to simplify how we make classic Jack-o-Lanterns and their ghoulish grins

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Design-Decoded-patent-jackolantern.jpg)

It’s not Halloween until you’ve carved a pumpkin.

But as the clock ticks down to All Hallows Eve—and you scramble to outdo that smug Heisenberg grin your neighbor carefully carved last weekend—you might have stepped back from the kitchen table, cursing the slimy, stringy gourd innards tangled around your hands, and wondered why you were doing this to yourself.

(Or, perhaps, if the money you dropped on that electric pumpkin carving knife was really worth it).

All arrows seem to point to an old Irish legend about a man named Stingy Jack, who convinced the devil not to send him to hell for his sins when he died. The trick was on Jack, though, when he did die later—heaven shut him out, too, for bargaining with the man downstairs, and he was left to wander and haunt the Earth. Irish families began to carve crude, wild faces into turnips or potatoes come Halloween, illuminating them with candles to scare Jack and other wandering spirits away.

When immigrants brought the tradition to America in the 19th century, pumpkins became the vehicle for ghoulish faces. In 2012, Farmers harvested 47,800 acres of pumpkins in 2012, crops worth $149 million, according to the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. This year, the National Retail Federation estimates consumers will spend $6.9 billion on Halloween products, including those handy carving tools and kits.

The genius behind those tools is a group smaller than you might think. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office says there have been fewer than 50 (probably closer to 30) patents issued for pumpkin or vegetable carving tools or kits, most of them issued in the past 40 years.

And while today we’ve become obsessed with clever ways to carve a pumpkin (yes, extremepumpkins.com does exist) most inventions stick to the classic Jack-o-Lantern face.

One of the earliest patents relied on simple tools — cords, plates and screws— to allow even the youngest and clumsiest among us to create a scary-looking gourd.

Harry Edwin Graves, from Toledo, Ohio—a state that yields the third highest number pumpkins in the United States each year—earned a patent in 1976 for his invention, which he called simply an “apparatus for forming a jack-o-lantern.”

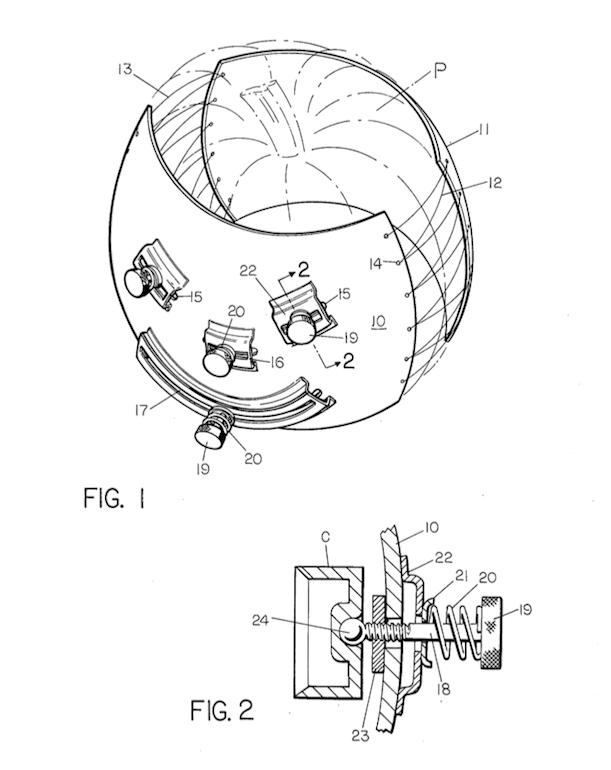

One of the earliest pumpkin carving inventions: plates and screws that carved out facial features. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

Graves knew, according to his application, that “It has been a very difficult, if not impossible, task for small children to make their own jack-o-lantern from a pumpkin” because the thick wall of the vegetable can be tough to puncture using kid-sized hands and arms.

His solution: a metal or plastic contraption that surrounded the pumpkin, with small plates in the shapes of a mouth, nose and eyes. By slipping the invention over the pumpkin, children can turn a screw on the front of each facial feature, engaging a blade that cuts through the shell and then retracts.

But threading plates together—or wielding a steak knife—was still for many a cumbersome task.

And so with the 1980s—along with cringe-worthy neon clothing choices, MTV, Michael Jackson, Madonna and Prince—came a decade bursting with new patents for carving pumpkins.

In 1981, Christopher A. Nauman, of Frederick, Maryland, earned a patent for a method of carving Jack-o-Lanterns that was safer, he said, because it relied on cookie-cutter facial features and not carving objects.

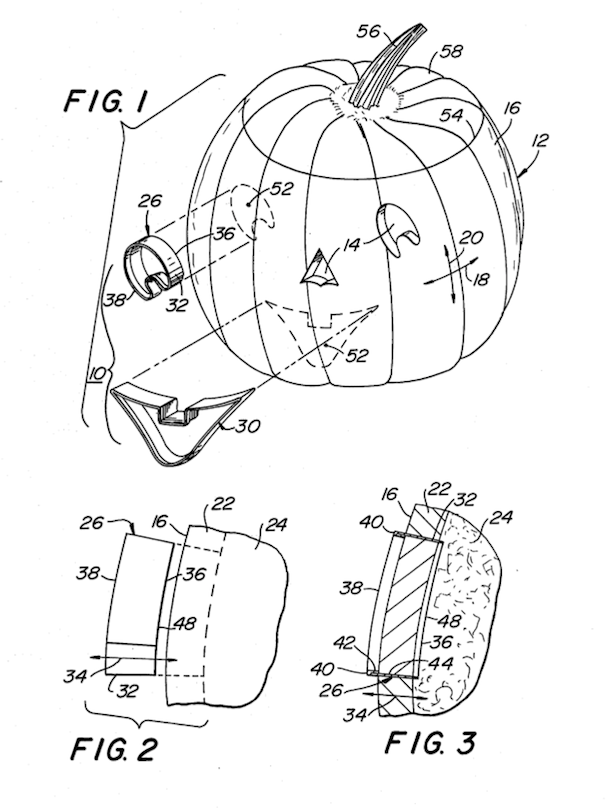

Christopher Nauman patented what feels like a weird cross between Halloween and Christmas: Cookie cutters shaped like eyes, ears, teeth and noses. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

While using cookie cutter shapes wasn’t a new idea, Nauman distinguished his design by contouring the cookie cutters to better fit against the curved surface of the pumpkin. And, when users hit the top edge of each shape, the cookie cutter presses directly through the pumpkin, which means users don’t have to go searching for pins or knives to pry the cookie cutters out of the pumpkin’s face.

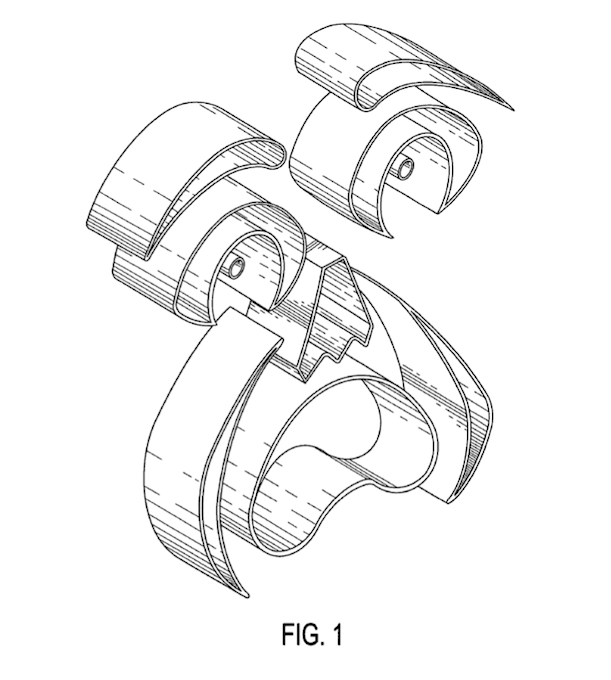

Cookie cutter-shapes were also the inspiration for Thomas C. Albanese’s design, but his 1987 patent—which he claimed could “overcome the shortcomings of the prior art”—included a detachable handle. The handle gives enough leverage to push the beveled edge of the shapes, from eyebrows to crooked teeth, through the pumpkin wall; the hollow shapes also hold on to the cut piece of pumpkin as it’s removed from the gourd, so stray hunks of the shell aren’t trapped inside the lantern, though admittedly that last step seems to work better in theory than in practice.

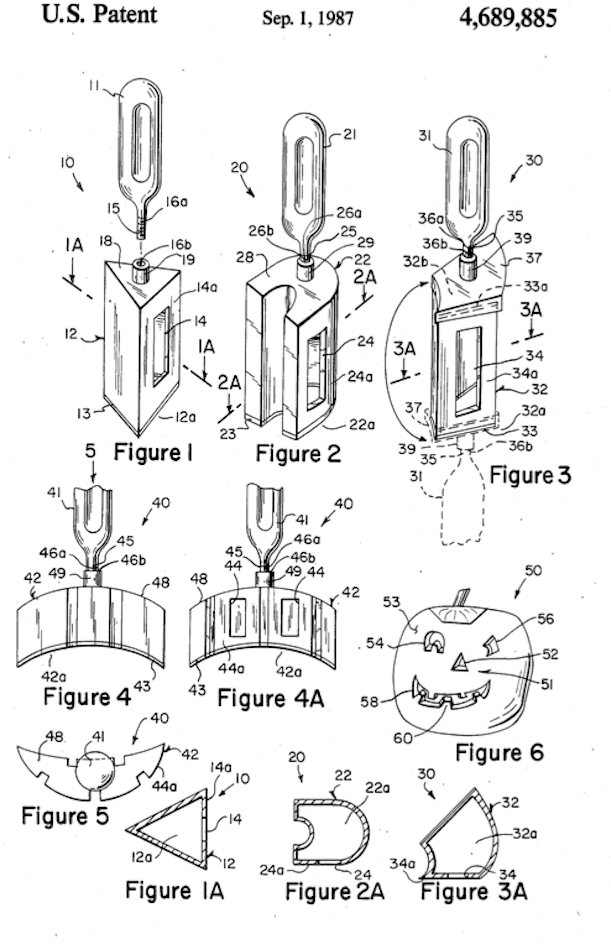

Thomas Albanese patented a handle for cookie cutter shapes—which in theory means you don’t have to wield a knife at all. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

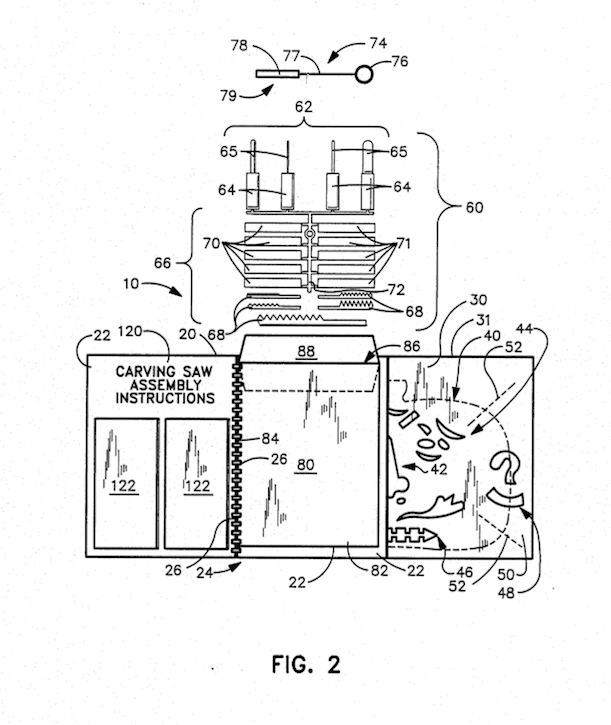

But the real advent of what we know today as pumpkin carving kits came in the late 1980s, thanks to a man named Paul John Bardeen.

Bardeen, according to patent documents, is considered among the first to develop tools that allowed Halloween lovers to carve intricate designs on their pumpkins, instead of crude, block-shaped faces.

He developed new saws and small knives, but more importantly, pattern sheets, which allowed pumpkin carvers to take a lot of the guesswork out of the process.

Bardeen died in 1983, but his children, wanting to continue his legacy, formed a company now known as Pumpkin Masters to sell the kits and continue to dream up ways to simplify or improve the carving process.

It’s safe to bet most people have used these kits at some point in their pumpkin carving careers. And for that, you can thank the Bardeen Family. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

Bardeen apparently never filed a patent of his own, but his son, John P. Bardeen, used his father’s design to earn his own patent on a pumpkin carving kit in 1989, taking the kit to the mass market for the first time. The kit packaged slightly more sophisticated saws and drills with a number of pattern sheets, decorated with a series of holes in the shapes of facial features and other designs. Carvers used a corsage pin to poke holes through the surface of the pumpkin, and after removing the sheets, connected the dots with cutting tools to form faces or drawings of cats and bats. A bonus: the kit also included an instruction book that detailed which tools to use when carving some of the kit’s designs.

Bardeen’s kit got traction in the late 1980s when he appeared on “Monday Night Football” with a pumpkin carved to show the likeness of the show’s hosts; he reportedly (did he or didn’t he? We can’t confirm?) went on a “pumpkin tour” in the years that followed, carving pumpkins for “Seinfeld” and the “Today Show,” among other stars, and perhaps sparking new imagination behind the lanterns people put out on their porches.

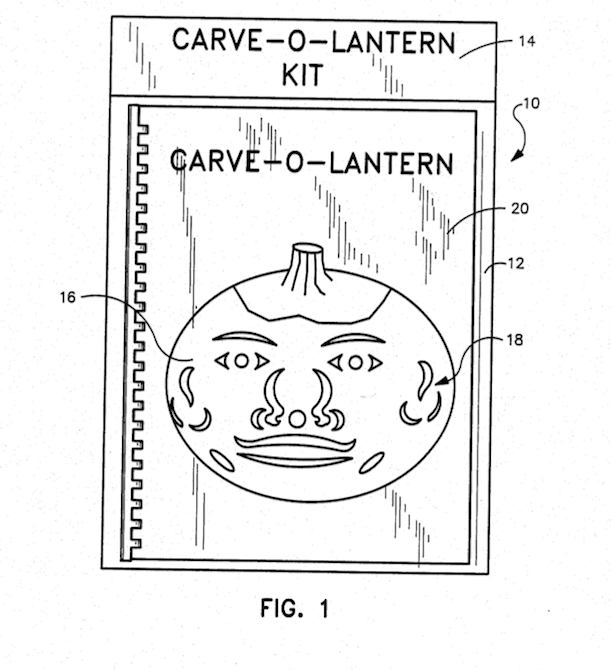

The Bardeens wanted to give families as many ways as possible to create the pumpkins of their dreams. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

But even after etching words, animals and celebrity faces into pumpkins became all the rage, the market for new pumpkin tools kept chugging to the tune of “Pumpkin Carving for Dummies”- or, more recently, avoiding the actual act of carving all together.

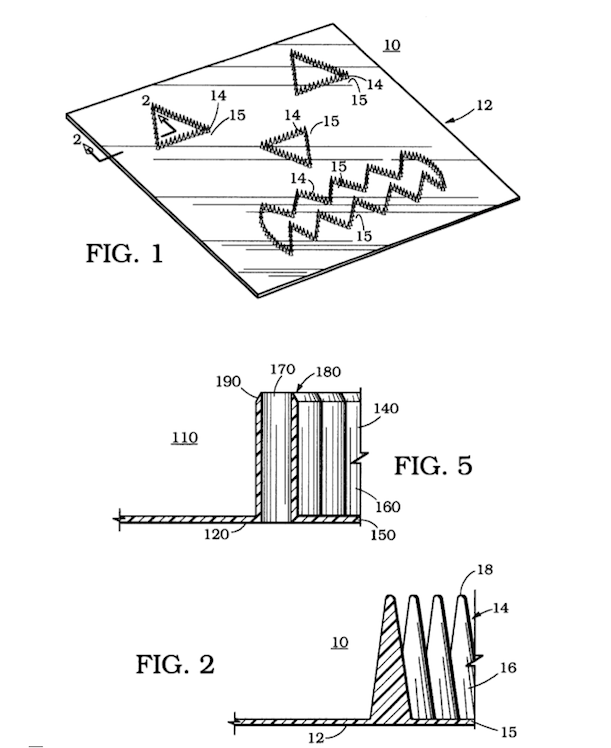

In 2000, John P. Bardeen’s former wife, Kea Bardeen, developed a kit that included transfer sheets so consumers could literally “slap and go.” Some sheets are pre-made, already stamped with bright colors, while others are drawn without color or blank, so they can be decorated and embellished with markers and paints. The designs are pressed and transferred onto the surface of the pumpkin with a transfer sheet and paste, water solvent or glue.

Carving not for you? Kea Bardeen made a kit for those that just want to color their pumpkins. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

The beauty of this design, for those who despise the thought of spending days picking stray pumpkin seeds off the floor, is choosing how much work to put into your pumpkin. It would be especially useful for young children, as the kit is essentially a giant coloring book (that makes, compared to paper and crayons, just a bit more of a mess). But going this route—which more or less makes your creation irrelevant after dark—is technically just pumpkin painting, an activity most of us preferred to put behind us come kindergarten.

Enter the lazy man (or woman)’s way to carve.

Taking the guesswork out of pumpkin carving since 2001, these plates will give you a fast (and symmetrical) Jack-o-Lantern face. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

In 2001, Michael A. Lani developed carving plates that poke holes into a pumpkin’s surface, but unlike Bardeen’s design, this invention does the hard work for you. The design involves a flexible plastic plate with pins arranged in the shape of a Jack-O-Lantern face, which lets you poke the design into a pumpkin with just a simple push of the plate — much faster than working through dozens of holes with a single corsage pin.

And for those of us for whom pins are too much work — or really need to let out some of that anger from the office— the Halloween pumpkin punch out kit might be the best option. The 2008 design by Laraine and Randy Reffert of Ohio includes metal facial features that you quite literally punch through the surface of the pumpkin, usually with a hammer.

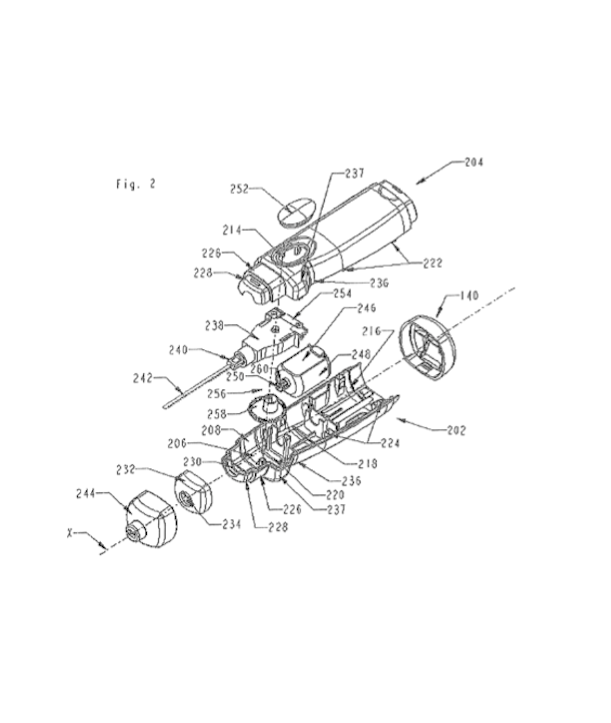

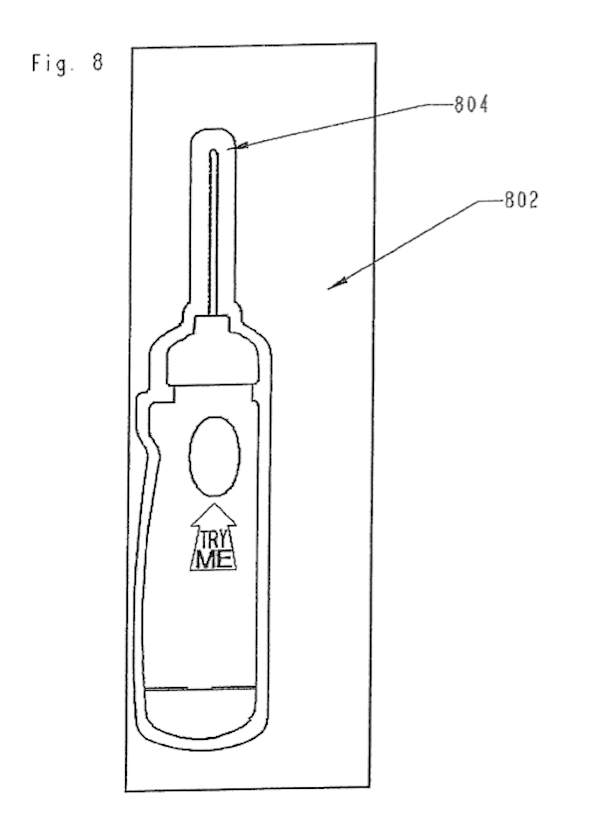

But even pumpkin carving has had to eventually join the electronics age.

In 2009, a group of inventors from Ohio patented an electric knife with a blade adapted to cut through the shell and pulp of a pumpkin—but, thankfully, “not readily cut the skin and flesh of humans.”

A group of inventors took carving to the next level in 2009 with this battery-powered pumpkin carving knife. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

The knife, though plastic, allows for “faster, more precise carving of pumpkins with less physical force being required.” The knife, powered by batteries, is turned on or off with a push button on the front of the handle so you can stop and go as needed.

With this electric pumpkin carving knife, you’re one button away from becoming a Jack-o-Lantern artist. Credit: United States Patent and Trademark Office

Now, everyone from Martha Stewart to the Boston Red Sox have printable templates on their site — and there are even ways you can carve any picture into the front of a pumpkin, too.

It seems the bar for Jack-O-Lanterns is climbing each year, and if you want to keep up it could be time to call in the big guns. A Google search for electric pumpkin carving knives didn’t yield any products from Emerald Innovations, LCC, to whom the patent is licensed, but similar products are available for anywhere from $4 to $34 — which could just be the price of having the best pumpkin on the block.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)