The Persians Revisited

A 2,500-year-old Greek historical play remains eerily contemporary

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/persians_1_631.jpg)

To the dramatist, all history is allegory. Deconstruct, reconstruct, adapt or poeticize the past, and it will confess some message, moral, or accusation. To that end, artists around the world have resurrected an obscure 2,500-year-old historical play, hoping it will shed light on one of the greatest political controversies of our time.

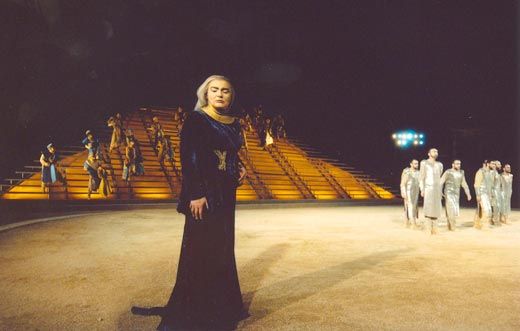

The oldest extant play and the only surviving Greek tragedy about a contemporaneous (rather than mythological) topic, The Persians was written by Aeschylus in 472 B.C. The play chronicles the 480 B.C. Battle of Salamis, one of the most significant battles in world history: As the turning point in the Persian Empire's downfall, it allowed the Greeks—and therefore the West's first experiment with democracy—to survive. Aeschylus, a veteran of the Persian Wars, also made the unusual choice of recounting the battle from the Persian perspective, creating what's generally seen as an empathetic, rather than triumphalist, narrative of their loss.

Today, the play is unexpectedly trendy. It has been produced about 30 times over the last five years. Why? Consider the plot: a superpower's inexperienced, hubristic leader—who hopes to conquer a minor enemy his father tried unsuccessfully to fell a decade earlier—charges into a doomed military invasion. The invasion is pushed by yes-men advisors and predicated on bad intelligence. And this all takes place in the Middle East. To anti-war theater folk, The Persians strikes the topicality jackpot.

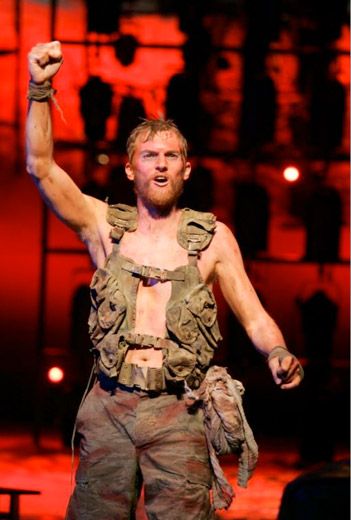

In the days after the 2003 Iraq invasion, National Actors Theatre artistic director Tony Randall canceled his spring season, deciding instead to produce The Persians because of America's "national crisis." Given the woodenness of existing translations, playwright Ellen McLaughlin was summoned and given six days to write a new version. Her poignant adaptation—inspired by the other translations, since she doesn't read Greek—was clearly informed by, although she says not tailored to, anger and bewilderment over America's sudden military action. In place of a homogenous chorus, she created a cabinet of advisors, representing "Army," "State," "Treasury" and other authorities. These advisors proclaim defeat "impossible" and "unthinkable," and present attacking the Greeks as "surely…the right thing because it was the thing we could do."

"It was dynamite," Randall told the Chicago Tribune about why he commissioned the play. "It was written in [the fifth century B.C.], but it was the most anti-Bush play you could find." Randall died in 2004.

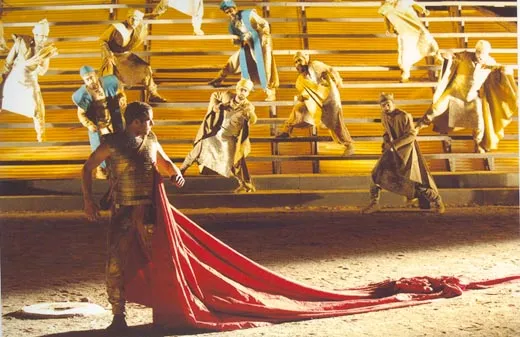

Randall's production received international attention, alerting other theater companies to the existence of this buried gem. Around 20 productions of McLaughlin's adaptation have followed. Many other versions of the play have been produced, too. Some have been quite faithful to Aeschylus, including the National Theatre of Greece's 2006 production. A few have made more overt contemporary references, recasting the play as a sort of political cartoon. An Australian playwright's adaptation renamed the characters after members of the Bush family.

Another production, by New York's Waterwell troupe, reconfigured the text as a variety show, adapting portions and themes of the play into skits or songs. For example, in response to the latent Orientalism of the play—as well as the anti-Arab bigotry that followed September 11, 2001—the actors taught the audience to curse the "filthy" Greeks in colorful Farsi slang. According to the production's director, one of these epithets was so vulgar that some of the play's Farsi-fluent theatergoers stormed out in disgust.

Audience members, critics, and political columnists alike have unfailingly described the play's parallels to contemporary events as "uncanny" or "eerie," and those who've opposed the Iraq war have generally appreciated Aeschylus' historical articulation of their objections to the war, such as his heartbreaking catalog of the war dead.

Today's audiences aren't the first to feel kinship with The Persians. It has enjoyed previous waves of revivals and so-called retopicalizations. As described in the 2007 book Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millennium, Renaissance-era productions of the play conflated the Persians with the Ottomans. In the last century, sporadic productions of the play recast the arrogant Persian prince as Hitler or other bullies. During the Vietnam War, U.S. productions critiqued internal, rather than external, hubris. Then, in 1993, an adaptation by Robert Auletta produced in multiple locations across Europe and America cast the Persian prince as Saddam Hussein. (That play has been revived at least once since 2003, and has been attacked as "anti-American.") A few post-2003 productions have also drawn parallels to non-Iraq conflicts, including urban violence and Greek-Turkish enmities.

And so, superficial character congruities aside, the play's message was intended to be timeless, symbolic, malleable. Even productions today will resonate differently from those mounted at the start of the war five years ago. In 2003, the play was a warning; now, to anti-war audiences, it's a counterfactual fantasy, one that concludes with the leader returning regretful, repentant, borderline suicidal—and condemned by the father he'd tried to out-militarize.

Now that Americans seem more accustomed—or anesthetized—to the daily stories of car bombs and casualties, Aeschylus' shocking relevance may be fading once again. The Persians is a sort of Greek Brigadoon, crumbling back into the desert sands until some new hapless society decides it needs Aeschylus' protean wisdom. And perhaps new parallels will emerge for future theatergoers, just as the father-son dynamic of the play was likely more salient in recent productions than those in other eras. "You don't do a play and make it timely," says Ethan McSweeny, who directed Persians productions in New York and Washington, both with McLaughlin's script. "You do a play and see what happens."