The Power of Imagery in Advancing Civil Rights

“Whether it was TV or magazines, the world got changed one image at a time,” says Maurice Berger, curator of a new exhibit at American History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Moving-Images-Withers-Sanitation-Workers-631.jpg)

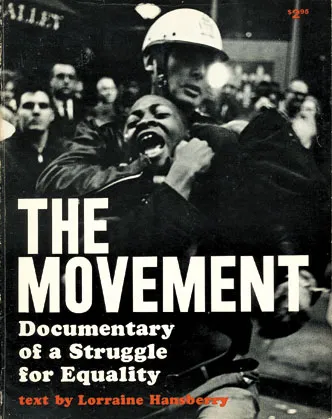

“One of the most extraordinary and least understood aspects of Dr. Martin Luther King’s leadership was his incisive understanding of the power of visual images to alter public opinion,” says Maurice Berger, standing in front of an oversize silk-screen portrait of the slain civil rights leader. Berger, who is a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture, is the man behind a moving and expansive new exhibition documenting the effect of imagery on the civil rights movement for the National Museum of African American History and Culture. (The traveling exhibition, “For All the World to See,” is on view through November 27 at the National Museum of American History.) Berger worked on the collection—movies, television clips, graphic arts and photography, most of it from eBay—over the past six years. But in a larger sense, he’s been putting it together his entire life.

In 1960, when Berger was 4 years old, his accountant father, Max, and his mother, former opera singer Ruth Secunda Berger, moved the family into a predominantly black and Hispanic housing project on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. “My world was not a world of whiteness when I grew up, which was great,” Berger says, because it gave him insights into black culture and racism. He recalls, for example, that he could walk unconcerned around a department store, while his black friends would be followed by store security guards.

In 1985, he met Johnnetta Cole, who was a professor of anthropology at Manhattan’s Hunter College, where Berger was an assistant professor of art history. Two years later, he and Cole, who would become director of the National Museum of African Art, collaborated on an interdisciplinary project, including a book and an exhibition at the Hunter College Art Gallery, called “Race and Representation,” which explored the concept of institutional racism. “We were the first large-scale art museum project to broadly examine the question of white racism as an issue for artists, filmmakers and other visual culture disciplines,” Berger says, “and that really started me on this 25-year path of dealing with two things that are most interesting to me as a scholar: American race relations and the way visual culture affects prevailing ideas and alters the way we see the world.”

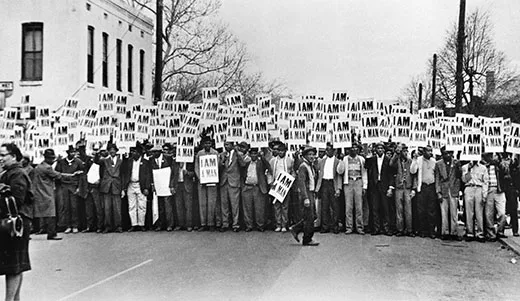

In the new exhibit, Berger examines how visual messages were used not only by movement leaders and the media, but also by ordinary people not mentioned in history books. “I really wanted to understand the level of human interaction on the ground,” Berger says. “Whether it was TV or magazines, the world got changed one image at a time.” He believes the most simple images can deliver an emotional wallop, such as a poster by San Francisco graphic artists that declares in red letters, “I Am a Man.” It was inspired by placards carried by striking black sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968—the strike that brought King to the city on the day of his assassination.

The exhibition takes visitors through themed sections, beginning with such stereotypical images as Aunt Jemima, followed by an exhibit of rare African-American magazine covers, which sought to counter stereotypes with images embodying pride, beauty and accomplishment.

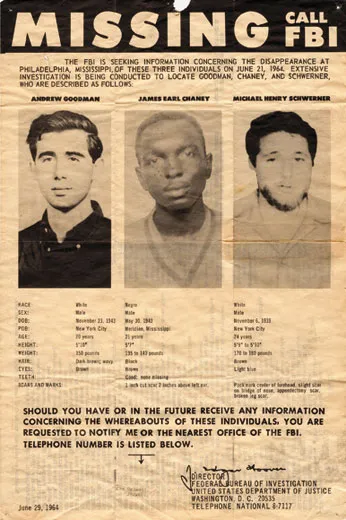

Farther along, Berger examines the 1955 murder and mutilation of 14-year-old Emmett Till, after he was accused of whistling at a white woman while visiting Mississippi. His gruesome death, brought starkly home by his mother’s insistence on having an open casket at his funeral in Chicago, became a rallying point for the civil rights movement. “She also directed photographers to take pictures of the body, saying, ‘Let the world see what I’ve seen,’” says Berger, explaining the exhibition title. “And I thought, well then I’ll answer Mrs. Till’s call. It’s this totally distraught, grieving mother, not a historian, not a political figure, who suddenly realizes that that one image could spur a revolution.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Arcynta-Ali-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Arcynta-Ali-240.jpg)