The Real Frida Kahlo

A new exhibition offers insights into the Mexican painter’s private life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/frida631.jpg)

Mexican painter Frida Kahlo is remembered today for her personal struggle and extraordinary life story as much as for her vibrant and intimate artwork. Kahlo was plagued by illness since youth and a bus accident at age 18 smashed her spinal column and fractured her pelvis, confining her to bed for months and leaving her with lifelong complications.

Though she had never planned on becoming an artist and was pursuing a medical career at the time of her accident, Kahlo found painting a natural solace during her recovery. It would become an almost therapeutic practice that would aid her in overcoming physical pain as well as the emotional pain of a turbulent marriage with muralist Diego Rivera and, years later, several miscarriages and abortions.

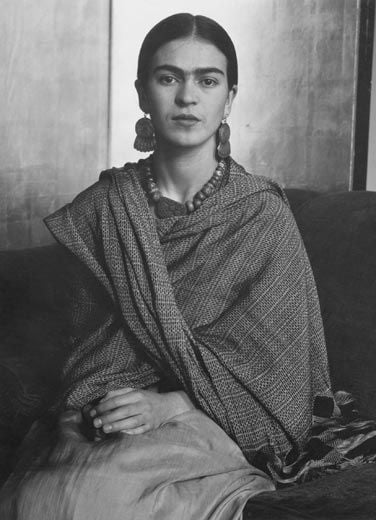

Despite the candidness of her work, Kahlo always maintained an image of poise, strength and even defiance in her public life. An exhibition at the National Museum for Women in the Arts (NMWA), "Frida Kahlo: Public Image, Private Life. A Selection of Photographs and Letters," on display through October 14, examines the dichotomy between Kahlo's self-cultivated public persona and the grim realities of her life. Commemorating Kahlo's 100th birthday, the exhibit is a collaboration between the NMWA, the Smithsonian Latino Center and the Mexican Cultural Institute.

The exhibit was inspired by the NMWA's recently acquired collection of Kahlo's unpublished letters to family and friends from the 1930s and 1940s, most of which document the four years Kahlo and Rivera spent living in the United States. The letters offer a glimpse into Kahlo's thoughts, her impressions of new and exotic places and her relationships with loved ones.

"She would pour her heart out into these letters," says Henry Estrada, public programs director at the Smithsonian Latino Center, who coordinated the translation of the letters. "She would do everything to convey these new experiences of San Francisco or New York. She would actually draw pictures of the apartment she was staying in and describe the beaches on the west coast. She would say things like 'mil besos,' which means 'a thousand kisses,' and kiss the letters."

The letters, which are accompanied by a selection of iconic Kahlo photographs by renowned photographers such as Lola Alvarez Bravo and Nickolas Murray and never-before-seen photographs of Kahlo's private bathroom at the Casa Azul in Coyoacàn, Mexico, act as a bridge between the images of the stylized mexicanista decked in traditional Tehuantepec dresses and pre-Columbian jewelry and those of medical supplies and corsets that underscored Kahlo's troubled existence.

But why would an artist who is so explicit in her artwork take pains to construct a public image that seems to mask her private life? "I think when she was in front of the camera she felt very different than when she was in front of the canvas, and she expressed something different," says Jason Stieber of the NMWA, co-curator of the exhibition. "She expressed her glamour, her Mexican heritage, her Communist leanings. She was expressing her strength, whereas in her paintings she's expressing her pain."

More than just a link between the two sides of Kahlo's persona, the letters may also offer significant new information for Kahlo scholars. Though biographers often depict Kahlo's relationship with her mother as strained and conflicted, the letters show remarkable tenderness and affection between mother and daughter and may prompt scholars to re-evaluate the way they look at her mother's impact on Kahlo's life and work.

"People credit her father with the fact that she was as strong a woman as she was, but it’s possible that her mother was also in large part responsible for that," Stieber says. "Her mother ran the household."

The letters track a particularly emotional time in Kahlo's relationship with her mother, as they coincide with her mother's declining health. Stieber believes the NMWA collection has the last letter Kahlo's mother ever wrote to her, where she describes how wonderful it had been to talk on the telephone—the first time she had spoken on the phone in her life.

Regardless of the problems Kahlo may have been facing, her letters reveal a love of life that never faltered. "The thing that really struck me was how much this artist enjoyed life and lived life to the fullest," Estrada says. "She was just vivacious and articulate and engaged with her environment, with people, with lovers, with friends, with family. She communicated and she did so with passion in her heart, not just in her artwork, but in her relationships with people."

Julia Kaganskiy is a freelance writer in Boston, Massachusetts.