The Rock Concert That Captured an Era

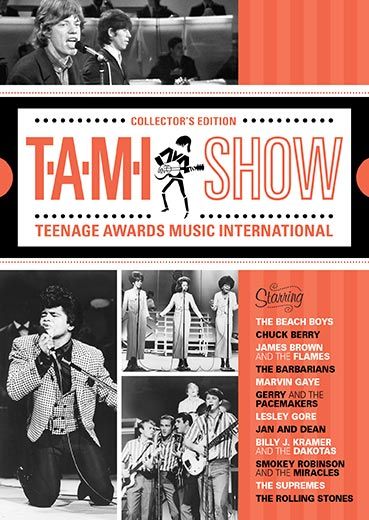

Featuring acts such as the Beach Boys, James Brown and the Rolling Stones, The T.A.M.I. Show defined popular music for a generation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Beach-Boys-TAMI-Show-631.jpg)

With movie attendance in a freefall in the late 1950s, Hollywood producers were trying everything to draw television viewers back into theaters. The number of moviegoers dropped roughly 70 percent in the years following World War II, from a high of 90 million a week in 1946 to 27 million a week in 1960. The producers hoped to attract teenagers through rock ‘n’ roll music: Elvis Presley starred in over 30 feature films during his career, and movies like The Girl Can't Help It boasted appearances by musicians like Little Richard, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. But most of these films were made by Hollywood veterans, who tended to look down on rock music and packed their films with established stars in hopes that they would mask the outdated production values. Their plots recycled old musical formulas, with singers lip-syncing to pre-recorded tracks instead of performing live. And the distribution system set in place often meant that performers would reach the screen months after their hits songs had faded.

A concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on October 29, 1964, not only changed Hollywood's attitude toward rock music, but helped define how rock would appear on screen and television in the future. The T.A.M.I. Show was photographed in Electronovision, a new process that enabled filmmakers to have a finished product in less than a month, and to get their prints into theaters while the acts and their material were still fresh.

Crucially, The T.A.M.I. Show was not just a vibrant cross section of Top 40 radio, it was made by industry newcomers who loved rock and its performers and understood how to capture the music on film. The associations forged during the making of the film lasted for decades. Director Steve Binder, musical arranger Jack Nitszche, choreographer David Winter and their crew members brought the T.A.M.I. Show style to television series like “Hullabaloo” and “Shindig.” The camera setups and editing schemes here were imitated in music documentaries like Monterey Pop and Woodstock. To a surprising extent, what we picture when we think about 1960s Top 40 radio came directly from The T.A.M.I. Show.

Electronovision was the brainchild of H. William “Bill” Sargent Jr., a self-taught electronics wizard who held some 400 patents for tape heads, amplifiers, camera components and other devices. Born in 1927 in Oklahoma, Sargent moved to Los Angeles in 1959. There he started the Home Entertainment Company, which specialized in closed-circuit screenings both in movie theaters and on television. In 1962, he produced a boxing match shown in theaters featuring Muhammad Ali (known then as Cassius Clay) that prefigured the sports pay-per-view market.

Sargent developed Electronovision, which promised high-quality video-to-film transfers of live performances. His cameras could capture 800 lines of registration, more than double the limit for home television reception. (In later years the cameras approached 1,400 lines of registration, the equivalent to today’s high-definition capabilities.) Sargent’s first production, Richard Burton's Broadway production of Hamlet, reputedly earned millions of dollars in theaters.

Sargent met Steve Binder while working together on a benefit broadcast for the NAACP. Twenty-three at the time, Binder was already directing two television series, “The Steve Allen Show” and a series on jazz for CBS. According to Binder, musician Jack Nitzsche first approached Sargent about filming a rock concert. A producer and arranger, Nitzsche co-wrote the hit “Needles and Pins,” and worked behind the scenes with songwriters and performers. For The T.A.M.I. Show, he assembled a house band whose members would later be known as the Wrecking Crew and could be heard on singles by everyone from the Monkees to Bing Crosby.

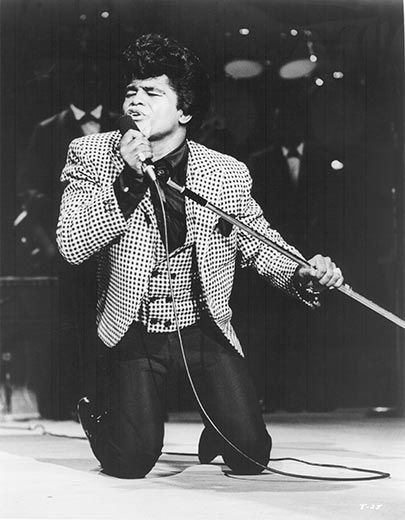

When it was released nationally in late December 1964, The T.A.M.I. Show was a chance for suburban teenagers everywhere to see acts that characteristically were confined to limited tours, as well as R&B acts that might never appear nearby. James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” became a tremendous hit a few weeks after the film hit opened, broadening his audience immeasurably. It was also a turning point of sorts for The Supremes, under Berry Gordy’s guidance an extremely polished singing trio. They were soon to become two singers backing up Diana Ross, due in part to her remarkable connection to the camera.

T.A.M.I. stood for either Teen Age Music International or Teenage Awards Music International, depending on whom you ask, described in a souvenir pamphlet as “an international nonprofit organization” that was going to help teenagers “establish a position of respect in their communities.” In a foreshadowing of today’s “American Idol,” teens were supposed to vote for their favorite musicians who were competing for awards. But Sargent's plans for both the organization and the voting fell apart when he lost control of the project because of mounting expenses.

As Binder remembers, “Sargent and Lee Savin, who got a producing credit, didn't have a clue about rock ‘n’ roll. They didn't know one act from another.”

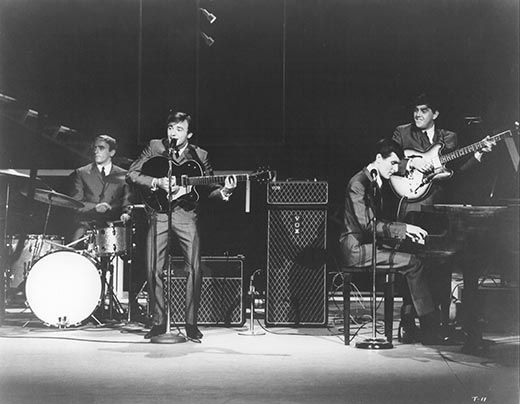

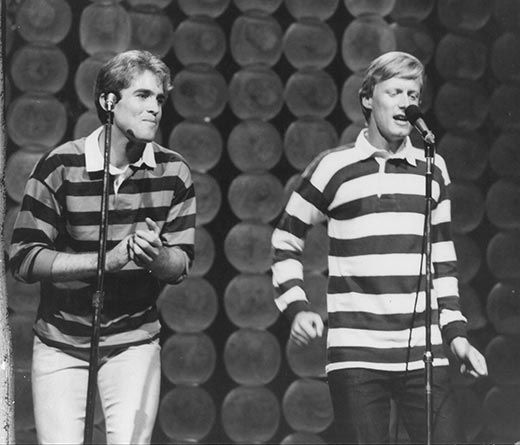

So it was up to Binder and Nitzsche to persuade musicians to join the project. Binder shared his manager with popular surf act Jan & Dean, who became the show’s hosts. As they did in the film, Jan & Dean would later open for the Beach Boys, arguably the most popular rock group in the country at the time (As well as the number one hit “I Get Around,” the group had five separate albums simultaneously on the charts in 1964). The Beach Boys’ performance was one of their last major public appearances with Brian Wilson; within two months of the concert, Wilson, the band’s creative force, would famously retire from the stage for almost two decades.

Detroit soul was represented by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Marvin Gaye and the Supremes. The first two were touring together in a Motown Records revue; Robinson had been the first artist producer that Berry Gordy had signed to the label. Already a bona fide star, Gaye, a part-time session drummer as well as a singer and composer, would blossom into one of the great talents in soul music on the strength of songs like “What's Going On.” The Supremes—Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard—were in the midst of a remarkable run of three number-one singles. On The T.A.M.I. Show, they performed two of the songs—”Where Did Our Love Go” and “Baby Love”—as well as two numbers from earlier in their career.

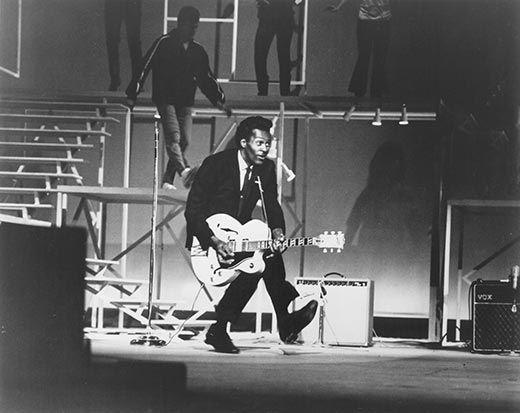

Among the rest of the acts Binder grabbed were British Invasion acts Gerry and the Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas, Lesley Gore (who typified New York’s Brill Building sound), and Chuck Berry who offered a reach back to the very beginnings of rock ‘n’ roll. The icing on the cake was James Brown and His Famous Flames, and the Rolling Stones, who were making their first American tour.

Two days of rehearsal gave Binder and his crew the opportunity to work out camera angles and editing patterns, but when it came to actual filming, Binder had to work “live.” With only one machine recording video, Binder cut among his four cameras on the fly, with no possibility of retakes, and no outtakes, insert shots or other post-production tricks that directors rely on today. This seat-of-the-pants approach led to what Binder calls his favorite shot of his career: an extreme close-up of a vibrant, ecstatic Ross as she sings “Baby Love.”

It also led to some frightening creative decisions, especially with James Brown. “In his case, I had never heard the songs or seen him perform them. And he refused to rehearse. So when he came out, we just had to wing it. I took a huge risk during one number when I kept the camera tight on James's face as he headed offstage. I told the cameraman, ‘I don't care if we're shooting the edge of the stage, the lighting equipment, instrument cases, whatever—you cover the artist.’ ” We take Binder’s approach for granted today, but at the time industry executives warned Sargent that the film—with its long takes, extended close-ups, and occasional glimpses of lighting stands and cameras—was unreleasable.

Of the 12 acts in The T.A.M.I. Show, five were soul or R&B artists. At a time of racial unrest, the filmmakers' choices took real courage, but Binder’s eye for talent was prescient. About her records, Diana Ross wrote, “I didn't know who was buying the music. Even then, although unaware, we were already crossing color lines and breaking racial barriers.” And as James Brown told reporter Steven Rosen, the film was “a masterpiece and the beginning of my career in one way.” Already a legend in soul circles, Brown was having trouble breaking through to white audiences. “I’d been getting that kind of response for a long time, but white people didn't get a chance to see me because they didn't go to the venues I was playing at.”

Sargent and Binder collaborated on the order of the acts, and were responsible for placing The Rolling Stones after Brown on the bill. (Binder recalls, “Brown just smiled and said, 'No one follows me.'“). Brown was a seasoned professional who simply modified his club show for a new audience. The Stones had yet to define themselves for American viewers –they didn’t have a significant radio hit in the U.S. at the time—and were still working out their stage personalities. (They had debuted on “The Ed Sullivan Show” just a few days earlier.) One breathtaking shot from a vantage point behind the musicians captures the hysteria that greeted the group; another follows singer Mick Jagger on a runway out into the audience, later a staple of his act.

Following James Brown forced The Rolling Stones to ramp up their energy level. Guitarist Keith Richards half-jokingly called following Brown the worst decision of the group’s career. Critic Stephen Davis wrote later that the group received support from Marvin Gaye. “Just go out there and do your thing,” Gaye told them. They abandoned their announced set list to concentrate on songs like “It’s All Over Now” that hadn't been released yet. It's a sizzling performance by a band that would endure for decades.

Teens embraced the film, perhaps because it showed their music without condescension. (It was an immediate hit, outgrossing teen-oriented competition like Beach Party.) Lesley Gore was 18 at the time, the Supremes and Mick Jagger 20, and Binder only 23.

After the stunning success of The T.A.M.I. Show, another production house, American International Pictures produced a sequel, The Big T.N.T. Show, without Binder’s involvement. The original production, however, entered a legal limbo phase that took decades to resolve. Beach Boys manager Murry Wilson (father to the three Wilson brothers in the act) demanded that the footage of his band be removed after the initial theatrical run. When Dick Clark obtained television rights, he further edited the material. A condensed version was briefly available on home video, and bootleg versions showed up sporadically, but it wasn’t until 2010 that the entire film became available on a legal DVD release. Today, there is still a palpable thrill to The T.A.M.I. Show, a sense that these now legendary musicians and filmmakers were discovering themselves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)