The Scene of Deduction: Drawing 221B Baker Street

From pen-and-ink sketches to digital renderings, generations of Sherlock Holmes fans have undertaken drafting the detective’s famous London flat

![]()

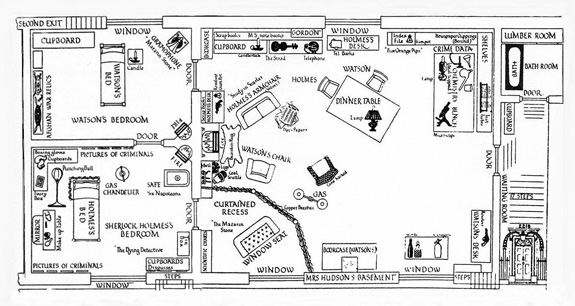

Ernest H. Short’s drawing of 221B Baker St. for The Strand Magazine (image: Ernest H. Short via Sherlockian)

When Sherlock Holmes walks into a crime scene, he displays the uncanny ability to deduce how the crime unfolded: where the criminal entered, how the victim was murdered, what weapons were used, and so on. Meanwhile, Scotland Yard must follow procedure, cordoning off and documenting the crime scene in order to reconstruct the criminal narrative. A crime scene sketch is an important part of this process. Typically, a floor plan is drawn before a building is constructed, but the crime scene sketch is a particularly noteworthy exception, as it not only verifies information in crime scene photographs, but includes dimensions and measurement that establish precise locations of evidence and objects relative to the space of the room. This information, properly obtained, can be used to assist both the investigation and the court case. But what if this investigative method is used on the flat of the world’s most famous detective?

221B Baker Street is rarely the scene of the crime (there are exceptions, such as “The Adventure of the Dying Detective”), but is instead the scene of the deduction, where Sherlock smokes his pipe or plays his violin while unraveling the latest mystery brought to his doorstep. Whether made by pencil or computer, these architectural drawings represent a reversal of the building-plan relationship. We’ve previously described the extent to which some Sherlock Holmes devotees have constructed their own version of 221B in tribute to the great detective. However, those with a curious mind who lack the resources to collect enough Victorian antiques to recreate the famous London flat are not excluded from the game. In fact, their pen-and-paper speculative reconstructions are not limited by cost and space. With such freedom, is it possible to determine what 221B Baker street truly looked like? As with the full reconstructions, there are many different speculative floor plans on 221B, ranging from the crude to the highly detailed. Most of these scholarly drawings are found exclusively in the pages of Sherlockian journals and club publications, but two of the most widely circulated plans will suffice to illustrate the complexities of rendering a literary space.

In 1948, Ernest H. Short drafted what would be one of the more widely circulated and thorough renderings of 221B when it was published in the pages of The Strand Magazine in 1950. Short’s drawing includes the rooms and furniture of Holmes’s flat, as well as sundry artifacts from his adventures and annotations noting the origin of each item. Traces of Holmes’s exploits and evidence of his proclivities line the walls and adorn the shelves. The Baker Street flat is a reflection of its occupant: his violin, his pipe, his costume closet. Chris Redmond, of the expansive Holmesian resource Sherlockian.net has called it “probably the most elegant re-creation of the sitting-room and adjacent rooms in Holmes and Watson’s lodgings.” His claim was likely true until 1995, when illustrator Russell Stutler drew 221B for an article in the Financial Times.

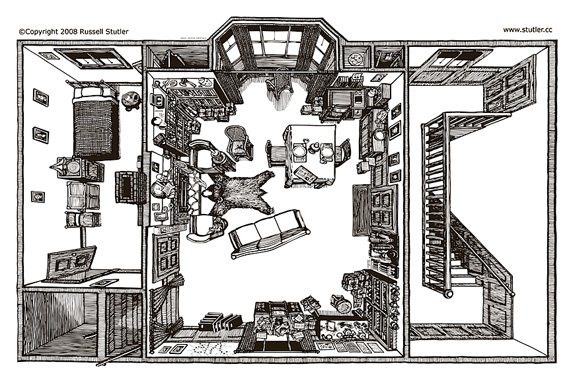

Russell Stutler’s drawing of 221B Baker St. for the Financial Times (image: Russell Stutler)

Stutler created his rendering after reading through every Sherlock Holmes story twice and taking extensive notes of every single detail mentioned about the flat. The details of Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories are full of contradictions that Sherlockians revel in rationalizing, and the various descriptions of Holmes’s flat are no exception. Most famously, “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone” presents some difficulties for those reconstructing 221B, as evidenced by some of the clumsy resolutions in Short’s drawing. Stutler notes:

“The Adventure of the Beryl Cornet” implies that Holmes’ room (called his “chamber”) is on the floor above the sitting room while “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone” clearly puts Holmes’ bedroom just off the sitting room where it communicates with the alcove of the bow window. If you need to reconcile these two descriptions you can assume that at some point in time, Holmes moved his bed down to the room next to the sitting room. This could be the same room just off the sitting room which had been used as a temporary waiting room in “The Adventure of Black Peter.” The room upstairs could then be used as a lumber room dedicated to Holmes’ stacks of newspapers and “bundles of manuscript…which were on no account to be burned, and which could not be put away save by their owner” as mentioned in the “The Musgrave Ritual.” “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons” does mention a lumber room upstairs packed with daily papers.

As we’ve seen previously, these ostensible inconsistencies in Conan Doyle’s stories can be quite rationally explained by a well-informed Sherlockian. After all, as Holmes reminded Watson in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.” I highly recommend reading Stutler’s full post, which includes a list of every reference used to create the image as well as a fully-annotated version of the above drawing.

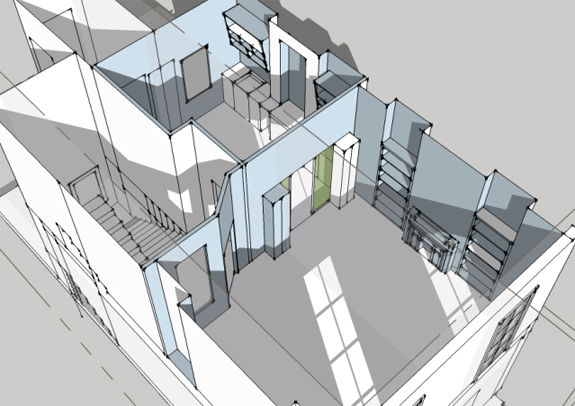

More recently, the BBC television series Sherlock has introduced an entirely new generation of potential Sherlockians to the world’s only consulting detective. Some of these men and women have already dedicated themselves to analyzing the series, which presents an entirely new canon—clever interpretations of the original stories—for mystery enthusiasts to dissect and discuss. Instead of thumbing through a text page after page in search of clues describing 221B, these new digital drafstmen are more likely to pause a digital video frame by frame to dutifully reconstruct, in digital form, the new version of the famous flat now occupied by Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes and Martin Freeman’s Watson. These contemporary Sherlockians turn to free drafting software or video games instead of pen and paper. The following renderings, for example, come from the free drafting program Sketchup and the video game Minecraft.

A Sketchup rendering of 221B Baker St. as seen in the BBC series “Sherlock” (image: livejournal user static lights via Sherlock BBC Livejournal)

A Minecraft rendering of 221B Baker St. as seen in the BBC series “Sherlock”(image: created by themixedt4pe via the Planet Minecraft forum)

If documentation, speculation, and informed reconstruction of a crime scenes make the criminal narrative clear, then perhaps applying the process to a “deduction scene” can do the same for the detective’s literary narrative. Like the crime scene sketch, the above deduction scene sketches of 221B Baker St are architectural drawings created ex post facto with the intent to clearly illustrate a narrative in pursuit of understanding. In “The Five Deadly Pips” Sherlock Holmes himself states that “The observer who has thoroughly understood one link in a series of incidents, should be able accurately to state all the other ones, both before and after.” By drawing 221B , the reader or viewer gains a more thorough understanding of one link in Holmes’s life, his flat, and can perhaps then, by Holmes’s logic, gain more insight into the life and actions of the famous detective that continues to capture the world’s imagination.

This is the sixth and final post in our series on Design and Sherlock Holmes. Our previous investigations looked into Mind Palaces, The tech tool of a modern Sherlock, Sherlock Holmes’s original tools of deduction, Holmes’s iconic deerstalker hat, and the mysteriously replicating flat at 221b Baker Street.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)