The Secret to the Modern Beehive is a One-Centimeter Air Gap

Beekeeping dates back to ancient Egypt. But in 1851, a Massachusetts minister invented a new hive. His secret? Something called “bee space”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130906093030hive-4701.jpg)

In 1851, Reverend Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth invented a better beehive and changed beekeeping forever. The Langstroth Hive didn’t spring fully formed from one man’s imagination, but was built on a foundation of methods and designs developed over millenia.

Beekeeping dates back at least to ancient Egypt, when early apiarists built their hives from straw and clay (if you happen to find a honeypot in a tomb, feel free to stick your hand in it, you rascal, because honey lasts longer than a mummy). In the intervening centuries, various types of artificial hives developed, from straw baskets to wood boxes but they all shared one thing: “fixed combs” that must be physically cut from the hive. These early fixed comb hives made it difficult for beekeepers to inspect their brood for diseases or other problems.

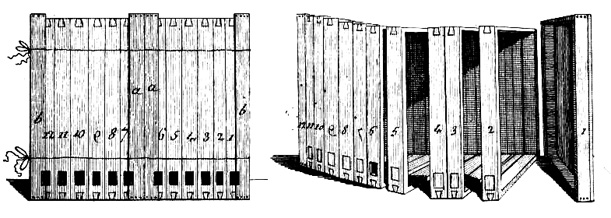

In the 18th century, noted Swiss naturalist François Huber developed a “movable comb” or “movable frame” hive that featured wooded leaves filled with honeycombs that could be flipped like the pages of a book. Despite this innovation, Huber’s hive was not widely adopted and simple box hives remained the popular choice for beekeepers until the 1850s. Enter Lorenzo Langstroth.

Francois Huber’s movable frame hive (image: Francois Huber, New Observations on the Natural History of Bees)

Langstroth wasn’t a beekeeper by trade. As a minister, he presided over a flock instead of a colony. After graduating from Yale in 1832, when the school was still led by an ordained minister, the Philadelphia-born Langstroth went on to become a pastor in Massachusetts and then, a few years later, a principal at a women’s school. It was around this time that he took up beekeeping as a means to mitigate severe bouts of depression—because nothing eases the mind like the incessant droning of drone bees.

Typical examples of modern beehives. The larger boxes at the bottom contain the brood and food for the bees. The smaller boxes, separated by a filter that prevents entry by the queen bee, contains the frames used for collecting honey. (image: jonathunder, wikimedia commons)

Langstroth pursued his hobby with the methodological rigor befitting his academic and theological background. He began by reading previous works on beekeeping and building hives following Huber’s designs, eventually experimenting with other types of construction. The process taught him the mechanics of beekeeping but also revealed that there was still some room for improvement. As Langstroth writes in his 1853 book Langstroth on the Hive and the Honey-Bee: A Bee Keeper’s Manual:

“The result of all these investigations fell far short of my expectations. I became, however, most thoroughly convinced that no hives were fit to be used, unless they furnished uncommon protection against extremes of heat and more especially of cold. I accordingly discarded all thin hives made of inch stuff, and constructed my hives of doubled materials, enclosing a ‘dead air’ space all around.”

This “dead air” gap—known today by the delightfully architectural term “bee space”—would have an added benefit. Langstroth discovered that bees would not build a honeycomb in a one-centimeter space—anything bigger, they would build a comb, anything smaller and the bees would fill it with propolis, the resinous composite also known as “bee glue” that bees make to construct their hives.

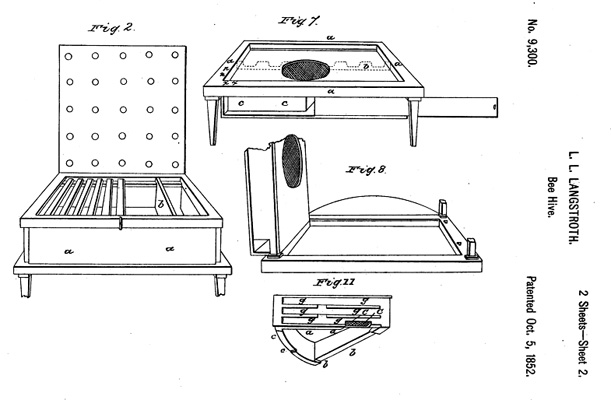

The notion of bee space, combined with the knowledge gleaned from the Huber hive, convinced Langstroth that “with proper precautions, the combs might be removed without enraging the bees, and that were capable of being domesticated or tamed, to a most surprising degree.” Realizing that honeycombs could be safely removed from the hive, Langstroth designed a system of removable frames that were suspended from the top of the box and set off from its sides by a one-centimeter gap. Thus, bees could build their combs in each frame, and the frames weren’t stuck to one another or to the box with propolis; they could be easily removed, replaced or moved to other hives without disturbing the bees or damaging the combs. Using Langstroth’s hive, it was now much easier to inspect and attend to the bees, and of course, to collect the honey. This was a very big deal in 1851 when honey was the primary means of sweetening food.

The hive was fabricated by a local cabinetmaker and fellow bee enthusiast Henry Bourquin, and the two men manufactured and sold the hive for several years. In a savvy marketing move, Langstroth opened his book on beekeeping with an advertisement for his hive enumerating its myriad benefits:

“Weak stocks may be quickly strengthened by helping them to honey and maturing brood from stronger ones; queenless colonies may be rescued from certain ruin by supplying them with the means of obtaining another queen; and the ravages of the moth effectually prevented, as at any time the hive may be readily examined and all the worms, &c., removed from the combs. New colonies may be formed in less time than is usually required to hive a natural swarm; or the hive may be used as a non-swarmer, or managed on the common swarming plan. The surplus honey may be taken from the interior of the hive on the frames or in upper boxes or glasses, in the most convenient, beautiful and saleable forms. Colonies may be safely transferred from any other hive to this, at any season of the year, from April to October, as the brood, combs, honey and all the contents of the hive are transferred with them, and securely fastened in the frames.”

Despite earning a patent on the design in 1852, other beekeepers began to copy Langstroth’s hive and the minister-cum-beekeeper spent years unsuccessfully defending his design from infringement. By the end of the century, Langstroth’s hive—or reasonable facsimiles of it—became the preferred hive for professional and amateur beekeepers, and it is still the most common artificial hive in use. And, in perhaps the greatest compliment that could be given to an industrial innovation, what was once a design feature—removable frames—is now, in most states, required by law.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)