The Smithsonian’s Ambassador of Jazz

Music curator John Edward Hasse travels the globe teaching the genre that revolutionized American music

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jazz-John-Edward-Hasse-631.jpg)

The sultry sound of a saxophone floats through a windowless room several floors beneath Washington, D.C.’s rush-hour traffic. John Edward Hasse adjusts his chair in front of a camera, tapping his toes as the big-band tune “Take the ‘A’ Train” plays on a CD.

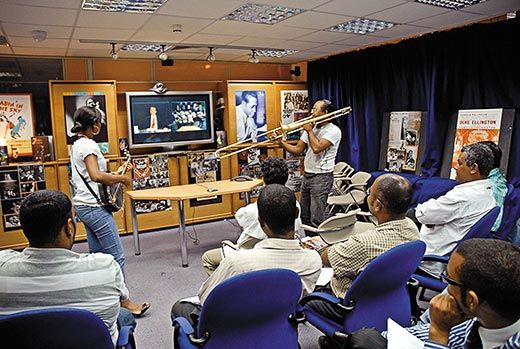

It’s 8:30 a.m. in the nation’s capital, but it’s 3:30 p.m. at the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi, Kenya, where a crowd has gathered to watch Hasse, via video conference, speak about the genre that revolutionized American music: jazz.

Today, his subject is Duke Ellington. “A genius beyond category,” Hasse tells his audience more than 7,500 miles away. “There were a lot of great musicians—composers, arrangers, bandleaders and soloists. But the best at all of those things? That was Duke.”

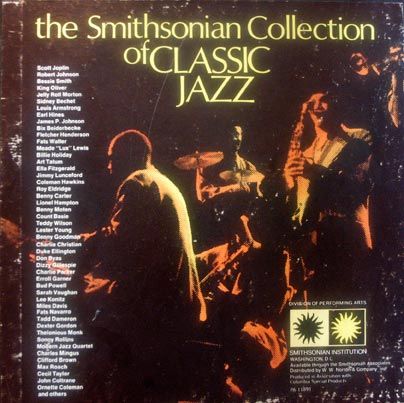

Hasse doesn’t just teach jazz; he embodies the things French artist Henri Matisse said he loved about it: “the talent for improvisation, the liveliness, the being at one with the audience.” As a producer, musician and lecturer, Hasse has toured 20 nations across six continents. He founded Jazz Appreciation Month, now celebrated in 40 countries and all 50 states, and his work as a music curator at the National Museum of American History and as an author has set the standard for jazz education across the country. Hasse recently teamed with an international panel of experts for the upcoming release of Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology, a six-CD, 111-track set that reconceives, updates and expands the 1973 Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz.

Jazz faces increasing competition from other music genres in the United States, yet it continues to find new audiences abroad. Many nations have developed their own jazz style —a fact Hasse says influenced the Smithsonian anthology—but enthusiasts abroad have few opportunities to learn about the genre’s American roots. While classical music began in Europe and Russia, and the folk tradition has long thrived in cultures around the globe, jazz is one of several musical styles conceived in this country.

So for the past decade, in cooperation with the State Department, Hasse has been America’s unofficial jazz ambassador-at-large. “Jazz implicitly communicates some of the most cherished core values of our society and culture: freedom, individuality, cultural diversity, creative collaboration, innovation, democracy,” he says. “It’s an art form that is such a vital part of American identity.”

Hasse often delivers his lectures via satellite. But he loves to teach and perform in person. In 2008, he traveled to Egypt accompanied by the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, a group he founded in 1990 to keep the importance of the music alive. When Hasse went to South Africa in 2006, a group of young boys, many of them orphans, traveled an hour and a half from their village of tin-roofed shacks to hear him speak. And when Hasse began to play a recording of Louis Armstrong’s “Hello, Dolly!” three of the boys sang along.

“I was just floored. They knew the words, every single one,” Hasse says. “When you can take someone like Armstrong, who was born more than 100 years ago in a country halfway around the world—and his music is able to leap with ease over geography, nationality, culture, demographics, everything else, and communicate and inspire young people—that itself is inspiring to me.”

Hasse plans to travel next spring to Moscow, where he hopes the response mirrors the one he received in Nairobi this past April. There teachers clamored for copies of his audio and video clips to share with students.

“One young man in Nairobi told me after hearing Armstrong, ‘You’ve changed my life forever,’” Hasse says. “Some of the world had never heard trumpet playing or singing like his before. There’s a hunger for things from America that are true, uplifting, positive, beautiful and inspiring. Jazz is that—the best of American culture.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)