The Splendor of Greene and Greene

A new exhibition celebrates the work of brothers Charles and Henry Greene, masters of American Arts and Crafts architecture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/greene_greene_631.jpg)

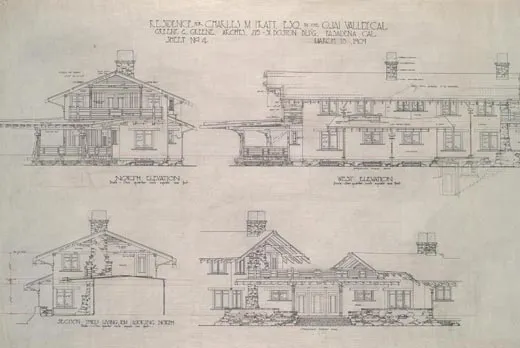

Overdue recognition for the brothers Charles and Henry Greene was a bittersweet triumph because it came partly in response to an irreparable loss. Arguably the greatest building by the architectural firm of Greene & Greene is the 1907 Blacker House in Pasadena, California, a masterpiece in the American Arts and Crafts style which is imbued with a love of Japanese architecture, traditional wood joinery, metal craftsmanship and classical proportion. Purchased by a Texas rancher and antiques collector who calculated that the furnishings were worth more than the $1.2 million purchase price, the Blacker House was stripped in 1985 of its art-glass windows, light fixtures and front door—a calamity that provoked the city of Pasadena to issue an ordinance protecting the interiors of its historic buildings. (The current owners of the Blacker House have commissioned replicas of leaded art-glass panels and light fixtures to substitute for the lost artifacts, and have begun commissioning reproductions of the original furniture for the house, which had been sold off even earlier at a yard sale in 1947 following the death of Robert and Nellie Blacker.)

Some of the far-flung Blacker furnishings have been reunited, along with a comprehensive collection of many other Greene & Greene designs, in the exhibition, “A New and Native Beauty: The Art and Craft of Greene & Greene,” which is on view at the Huntington in San Marino, California, through January 26, 2009. For the first time, a Greene & Greene exhibition will then travel outside California, first to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. (March 13-June 7, 2009) and then to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (July 14-October 18, 2009). Because the Greenes designed furnishings only for specific houses and not as production pieces, the objects are very rare and have become extremely expensive.

The Greene brothers learned carpentry and metalworking as high school students, and their designs display a craftsman’s know-how. “Their work is truly beautiful and beautifully made, and their furniture is more ergonomic than some of the furniture of the period, which is not as attuned to the human body,” says Edward R. Bosley, who curated the exhibition with Anne E. Mallek. (Bosley is the director of the one intact Greene & Greene residence, the magnificent 1908 Gamble House in Pasadena; Mallek is the house museum’s curator.) One of the goals of the curators was to re-create groupings of furniture and artifacts from the houses.

“Not only do the pieces not look right outside of their house, they don’t even look right out of their room,’ says Bosley. Since the furnishings are widely dispersed, Mallek and Bosley had to do some creative detective work to track them down. “There’s a table lamp from the Blacker House living room where one person owns the base and another person owns the shade,” he explains. “We’ve been able to bring them back together for this show.” In another act of ambitious restoration, the curators have had part of the Arturo Bandini House, a 1903 Pasadena residence that was demolished a half-century ago, reconstructed for the exhibition.

In their loving gaze across the Pacific toward Japanese craftsmanship and their passionate use of local wood and stone, the Greenes produced a hybrid architecture that is a uniquely Californian achievement. And they did it in a very limited time and place. Almost all of their buildings were in Pasadena, in Los Angeles County, and most of their masterpieces were constructed during a very short period, from 1906 to 1911.

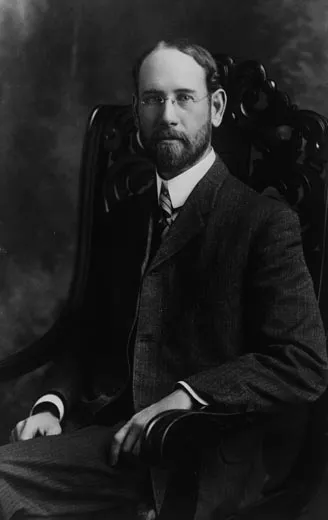

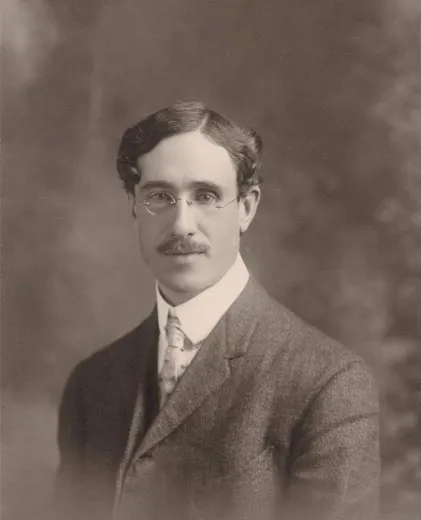

Descended from old New England stock, the Greene brothers grew up together in Cincinnati and St. Louis, studied architecture together at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and relocated together to Pasadena in 1893. At the time, the town was beginning to boom as a winter resort, favored by many of the Greenes’ fellow Midwesterners. These winter residents became the principal clients of the firm Greene & Greene. “California, with its climate, so wonderful in its possibility, is only beginning to be dreamed of,’ Charles wrote, soon after arriving. The brothers were 25 and 23 when they opened their office in Pasadena in January 1894. Within three years, they had moved to a central Pasadena building of their own design. For the wealthy clients who could afford their work, they were a godsend. The Greenes designed everything—not just the house, but the landscaping, the fittings, the furniture, the carpets. Like their contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright, they wanted control over the entire environment. “The primary difference with Frank Lloyd Wright is that the Greenes worked in one small area of the country and didn’t have the drive to expand their practice beyond Southern California,” says Bosley.

Both brothers married at the turn of the century: Henry in 1899 to a boarder at his aunt's Greene & Greene house, Charles in 1901 to an English heiress who was living a block from the house he shared with his parents. Charles, who was the elder of the two, was always viewed as the artist, Henry as more of the businessman, although the two men designed as a team. In 1909, Charles took a nine-month holiday in England. When he returned, he began to withdraw from his full-time involvement in the firm. He wrote a novel about a young architect who is kidnapped by a beautiful opera diva to design her house on a tropical island, and in 1916 he moved north, with his wife and five children, to the artists' colony of Carmel. Although Henry continued to practice architecture, with long-distance collaboration from Charles, the name Greene & Greene was discontinued in 1922. This arrangement may have suited them personally, but the legacy suffered. As a solo architect, Henry enjoyed less conspicuous success, while Charles dedicated himself to his artistic and spiritual endeavors, becoming a Buddhist. Although the men stayed on good terms, their work was eclipsed by changing fashions, and was only rediscovered seriously in the 1970s.

For the Greene brothers, every feature of a house contributed to an overall unity of feeling. Nothing can substitute for the experience of visiting the magnificent Gamble House in Pasadena, which is managed by the University of Southern California and directed by Bosley. But in place of that, the current exhibition goes a long way toward conveying how the Greene brothers raised the Arts and Crafts aesthetic of the early 20th century to its consummate American expression.