The Story Behind the Peacock Room’s Princess

How a portrait sparked a battle between an artist–James McNeill Whistler—and his patron–Frederick R. Leyland

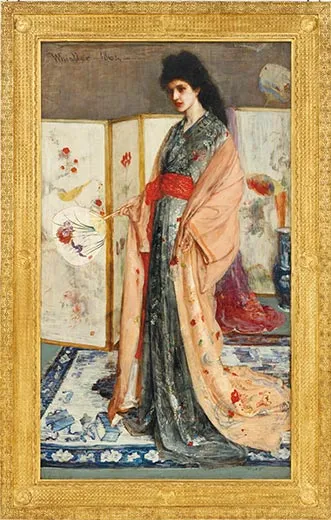

The great American expatriate painter James McNeill Whistler is best known, of course, for his Arrangement in Grey and Black, a.k.a. Whistler’s Mother, an austere portrait of a severe woman in a straight-backed chair. But judging Whistler only by this dour picture (of a mother said to have been censorious toward her libertine son) is misleading; the artist delighted in color. One painting that exemplifies Whistler’s vivid palette, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, constitutes the centerpiece of the Peacock Room at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art.

The work was owned by English shipping magnate Frederick R. Leyland in 1876 and held pride of place in the dining room of his London house, where he displayed an extensive collection of Chinese porcelain—hence the painting’s title. The subject was Christina Spartali, an Anglo-Greek beauty whom all the artists of the day were clamoring to paint. In 1920 the Smithsonian acquired the painting and the room (essentially a series of decorated panels and lattice-work shelving attached to a substructure). A new Freer exhibition, “The Peacock Room Comes to America,” celebrates its splendors through April 2013.

The Princess is also featured on the Google Art Project (googleartproject.com), a site that employs Google’s street-view and gigapixel technologies to create an ever-expanding digital survey of the world’s masterpieces. The average resolution for displayed works is seven billion pixels—1,000 times that of the average digital camera. This allows Internet users to inspect works up close, as if with a magnifying glass held just inches from a priceless painting.“Gigapixel reproduction is a real game changer,” says Julian Raby, director of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, making a Web view of a painting “an emotional experience.”

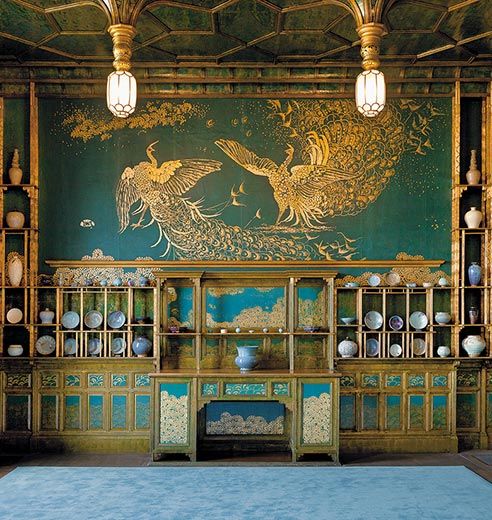

The Peacock Room (named for the birds Whistler painted on its shutters and walls) reflects the tension between the artist and his first significant patron. Leyland had hired Thomas Jeckyll, a prominent architect, to design a display space for his mostly blue and white Qing dynasty (1644-1911) porcelain collection. Because The Princess was hung over the fireplace, Jeckyll consulted Whistler about the room’s color scheme. While Leyland headed back to Liverpool on business, Jeckyll, having health problems, stopped overseeing the work. Whistler, however, pressed on, adding many design details, including the peacocks on the shutters.

In a letter to Leyland, Whistler promised “a gorgeous surprise.” Leyland was surprised all right, by embellishments far more extensive and expensive—some 2,000 guineas (about $200,000 today)—than he had anticipated. “I do not think you should have involved me in such a large expenditure without previously telling me of it,” he admonished Whistler.

After Leyland agreed to pay only half, Whistler did some more work on the room. He painted two more peacocks on the wall opposite The Princess. The birds faced each other, on ground strewn with silver shillings, as if about to fight. Whistler titled the mural Art and Money; or, the Story of the Room. Then Whistler painted an expensive leather wall covering with a coat of shimmering Prussian blue, an act of what might be called creative destruction. According to Lee Glazer, curator of American art, after Whistler finished in 1877, Leyland told him he would be horse-whipped if he appeared at the house again. But Leyland kept Whistler’s work.

Leyland died in 1892. A few years later, Charles Lang Freer, a railroad-car manufacturer and Whistler collector who had earlier bought The Princess, acquired the Peacock Room. He installed it in his Detroit mansion as a setting for his own extensive collection of Asian pottery and stoneware. He bequeathed his Whistler collection, including the Peacock Room, to the Smithsonian in 1906, 13 years before his death. For the new exhibition, curators have arranged the room as it looked after coming to America, with the kind of pottery and celadon pieces that Freer collected and displayed, instead of the blue and white porcelain favored by Leyland.

Whistler’s sophisticated color scheme presented challenges even to Google Art’s state-of-the-art technology. “The shadows and subtle colors proved a huge problem for the camera,” says Glazer. “I can’t help but think that Whistler would have been pleased.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)