The Swimsuit Series, Part 2: Beauty Pageants and the Inevitable Swimsuit Competition

In the latest chapter of the series, we look at how bathing suits came to be an integral part of the Miss America competition

Beauty contest, by Reginald Marsh, c. 1938-45.

Beauty resists definition. One might say it does so by definition: The subjective thing called beauty cannot be measured, quantified or otherwise objectively evaluated. Which isn’t to say we haven’t tried! Yes, the beauty pageant has been around a long time.

It was not long after Henry David Thoreau said that the “perception of beauty is a moral test” that his contemporary P.T. Barnum inaugurated the world’s first official beauty pageant, which was staged in 1854 and which was deemed so risqué that Barnum had to tone it down by asking women to submit daguerreotypes for judging instead of hosting a live show. From there, legend has it that the first “bathing beauty pageant” took place in the beach town of my youth, Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, where in the 1880s, the event was held as part of a summer festival to promote business. According to some digging done by Slate, although referenced frequently in literature and film, that tale may be a tall one.

The Miss America pageant was first held in 1921 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and presided over by a man dressed like King Neptune. Sixteen-year-old Margaret Gorman from Washington, D.C. took home the golden Little Mermaid trophy. And yet the beauty of this beauty pageant was secondary to commercial interests; as with many American cultural traditions, what became the Miss America pageant began as a promotional stunt, in this case promoting tourism in Atlantic City beyond the summer months.

Ever since, the bathing suit competition has remained an integral part—or, let’s face it—the integral part—of most beauty pageants. (Even after the talent categories were introduced, and the contestants started talking, which hasn’t always been successful: Remember the Miss Teen USA 2007 pageant?) Here’s a more interesting reel: a 1935 Texas pageant where the idea of beauty was so rigidly defined, in such a literal sense, that contestants tried to fit into wooden cutouts of the ideal female figure while in their bathing suits.

In the first segment in our series about bathing suits, we looked at the history. Today we see suits through the lens of the beauty pageant—the judging, the locale, the styles and requirements for entry—all of which can be seen in many items from the Smithsonian’s collections.

Such as this photo—

—on the back of which is written, by hand:

“You’ll never find me in this mob—but I was the only ‘judge’ in this beauty contest in Long Island, New York, it was my ‘first’ (in the 1920′s).” The judge was a young Alberto Vargas, a featured illustrator of busty beauties for Playboy.

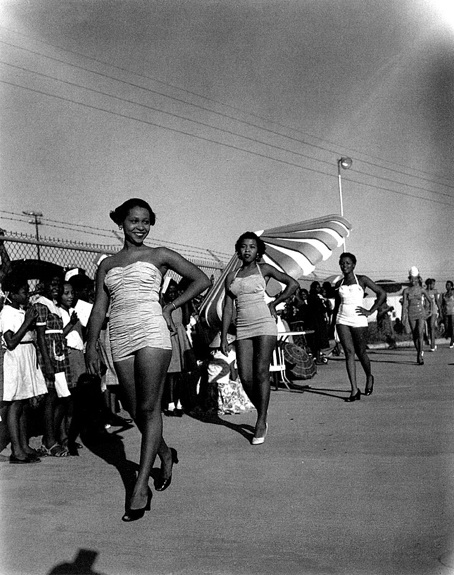

Here we see an African-American beauty contest in Mississippi at the dawn of the civil rights era. The contestants are strutting their stuff, and Anderson shot the scene as you would at a national contest on TV—angled up, from the best runway seat—except the blacktop and chain-link fence belie the setting. An excerpt from the Oh Freedom! online exhibition reads:

In fact, many beauty pageants at that time, including Miss America, allowed only white women to compete. It was not until 1970 that the first African American contestant reached the national Miss America competition, two years after the Miss Black America Pageant had been inaugurated in protest.

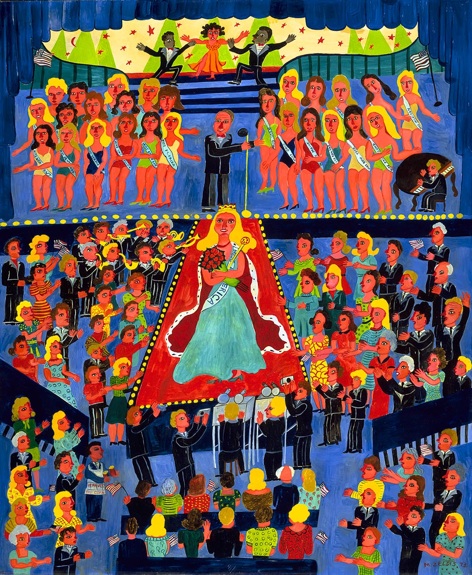

Around that time, artist Malcah Zeldis addressed the racial coding of beauty pageants in this painting:

Zeldis, a youthful kibbutznik in Israel who came back to the United States and started painting satires of American riturals like national holidays, weddings, and of course, the Miss America pageant, contrasts the blond beauty celebrated at the center with the less blond, less white onlookers.

Even for Zeldis, there is a winner. Because it wouldn’t be a beauty pageant without a winner. And she wouldn’t be a winner without the tiara placed atop her head. One of those tiaras, from the 1951 Miss America pageant, made its way into the Smithsonian’s collection a few years ago. In this 2006 article from Smithsonian, Owen Edwards explains how and why it was acquired:

Then, 1951′s Miss America, Yolande Betbeze Fox, contacted the museum from her home in nearby Georgetown and offered not only her crown but also her scepter and Miss America sash. According to Shayt, the “perfectly delightful” Fox set no conditions for the display of her donations. “She just wanted the museum to have them,” he says.

Fox may have been the most unconventional Miss America ever. Born Yolande Betbeze in Mobile, Alabama, in 1930, she comes from Basque ancestry, and her dark, exotic looks were hardly typical of beauty contestants in the ’50s. But her magnetism, and a well-trained operatic voice, focused the judges’ attention.

Betbeze wore the fabled crown uneasily. In 1969, she recalled to the Washington Post that she had been too much of a nonconformist to do the bidding of the pageant’s sponsors. “There was nothing but trouble from the minute that crown touched my head,” she said. For one thing, she declined to sign the standard contract that committed winners to a series of promotional appearances. And one of her first acts was to inform the Catalina bathing suit company that she would not appear in a swimsuit in public unless she was going swimming. Spurned, Catalina broke with the Miss America Pageant and started Miss Universe.”

Quite a contrast to our stereotypes about these competitions. As with the evolution of bathing suits from shield-your-eyes modesty (More fabric! Less skin!) to boldly embracing the iconic All American Girl and her skimpier red one-piece suit (and then plastering it on your bedroom wall), bathing suits and their wearers have never stopped causing titillation. The discomfort and controversy back in the 1950s around Yolande Betbeze Fox’s Miss America win, based on her beauty among other things, and her subsequent refusal to wear her suit for promotional purposes (i.e., to be checked out some more) exemplifies the push-pull Americans have felt acknowledging sexuality, judging beauty and showing a little bit of skin.

Images: Smithsonian collections

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)