The Top 10 Moments of Bob Dylan’s Career

We have selected 10 of the many pivotal events that have shaped his tumultuous life

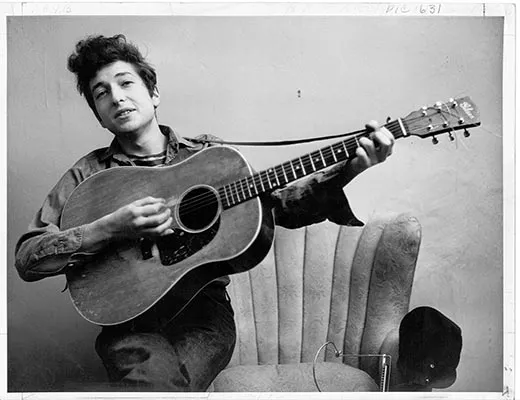

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bob-Dylan-Newport-Folk-Festival-1964-631.jpg)

"I'm a firm believer in the longer you live, the better you get." - Bob Dylan

Dylan said that in 1968, when he was 27. He turns 70 this month, as enigmatic as ever, a traveling troubadour on a self-proclaimed Never Ending Tour that began in 1988 and saw him playing 102 shows last year. He has been the young protest singer claiming he’s unconcerned with politics, the confessional songwriter who has offered as many myths as truths about his personal life, and the aging chronicler of the American folk songbook.

Here are 10 defining Dylan moments.

1. The Teen Rebel With a Cause

Growing up in Hibbing, Minnesota, a young Robert Zimmerman, "Zimbo" to his classmates, started playing the piano at 11 before shifting to a cheap acoustic guitar and falling for the songs of Hank Williams, Elvis Presley and Little Richard. As a young teen, Dylan fixated on the actor James Dean, pasting pictures on his bedroom walls. He was a rocker first, though, playing Little Richard tunes with his band, The Shadow Blasters, at a Hibbing High talent show on April 5, 1957.

2. Landing Up on the Downtown Side

He arrived in New York on January 24, 1961, after a meandering cross-country journey with two University of Wisconsin students. Depending upon which version you believe, he either headed out the next morning or four mornings later to meet Woody Guthrie, whom he described as “the true voice of the American spirit.” Guthrie, mostly confined to Greystone Park Hospital, was fading away with Huntington’s Disease. They struck up a friendship. Back in Greenwich Village, where he played Woody’s tunes in the coffeehouses, Dylan soon wrote "Song to Woody," one of two originals on his debut, Bob Dylan, recorded for Columbia in just two afternoons for the princely sum of $402. The disc, released in March 1962, sold just 5,000 copies its first year, and there were reports the label might drop Dylan.

3. Pellets of Poison Flooding Their Waters

In late September 1962, with the nuclear sword of the Cuban missile crisis hanging over the world, Dylan sat down at an old Remington typewriter and pounded out an apocalyptic poem titled “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” set to the melody of “Lord Randall,” a folk ballad. “The words came fast, very fast. It was a song of terror,” Dylan said later. “Line after line, trying to capture the feeling of nothingness.” Together with “Blowin’ in the Wind," “Masters of War” and “Talking World War III Blues,” “Hard Rain” would establish Dylan as the protest singer for a generation with the release of his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in May 1963.

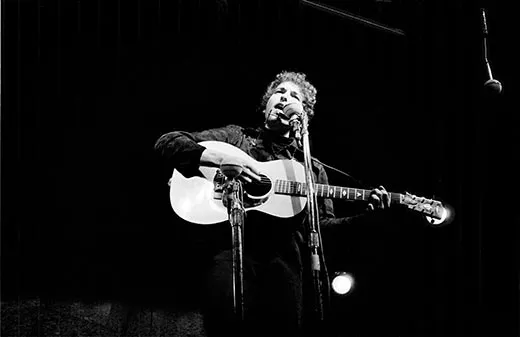

4. To Be on Your Own

On July 25, 1965, Dylan took the stage at the Newport Folk Festival, where he was an acoustic icon, with members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and famously plugged in. In what may be the most debated 16-minute set in popular music, they played howling versions of “Maggie’s Farm,” “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineeer,” an early draft of “It takes A Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” Many in the audience booed, labeling him a Judas to his folk followers. “Like a Rolling Stone,” released that week and later the lead track on Highway 61 Revisited, made Dylan a star, reaching second on the American charts. Depending upon the interpretation, the crowd booed because Dylan had gone electric, the sound was terrible or he played only three songs.

“I had a hit record out so I don’t know how people expected me to do anything different,” Dylan said two decades later.

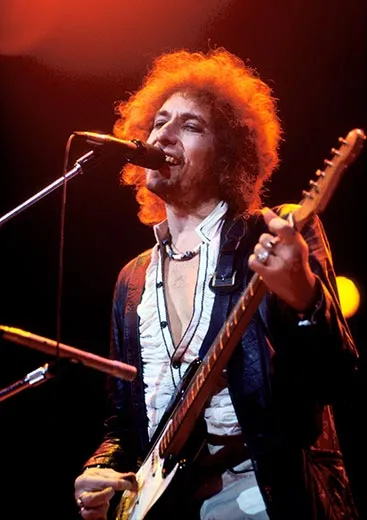

5. Everybody Must Get Stoned

During the first three months of 1966, Dylan took part in an improbably arranged marriage to a group of good ol’ boys from the Nashville studio set with no idea who he was. Their union created arguably the greatest double album in rock history, Blonde on Blonde. The sessions produced “Visions of Johanna,” “Sad Eyed Lady of The Lowlands,” “Just Like a Woman” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again.” “The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on individual bands in the Blonde on Blonde album," Dylan said more than a decade later. “It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound. It's metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up.”

6. This Wheel’s On Fire

“It was real early in the morning on top of a hill, near Woodstock,” Dylan said. I was drivin’ right straight up into the sun... I went blind for a second and I kind of panicked or something.” Dylan braked his Triumph 650 Bonneville motorcycle, locking the rear wheel and sending him sailing over the handlebars. The extent of his injuries on July 29, 1966. are foggy, like so many details of his life, although he was later seen wearing a neck brace. No police report was filed. In his autobiography, he barely mentions the accident, confessing: “Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.” That he did. While he continued his prolific writing, the songs were quieter, more introspective. He hunkered down in Woodstock for a few years raising his family and would not tour again until 1974.

7. A Simple Twist of Fate

Dylan dropped in on a painter and teacher named Norman Raeben, then 73, in New York during the spring of 1974 and spent a few months working with him, along with other students, for eight hours a day, five days a week. To Raeben, Dylan was just another student, one he frequently called an idiot. Raeben, Dylan said a few years later, “looked into you and told you what you were. He taught me how to see in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt.” The first album after the Raeben lessons was Blood On the Tracks, a masterpiece that reinvented Dylan as an intensely personal songwriter willing to examine the raw, dark side of love, notably on “Tangled Up in Blue.”

8. Gotta Serve Somebody

the end of a San Diego show on November 17, 1978, a fan, perhaps noticing Dylan faltering in poor health, threw a small silver cross on stage. Dylan picked it up. A night later in a Tucson hotel room, he says Jesus appeared and put his hand on him. “I felt it,” he said. “I felt it all over me.” In 1983, after two evangelical albums, Dylan set aside the fire and brimstone. “It’s time for me to do something else,” he said. “Jesus himself only preached for three years.”

9. Walking That Endless Highway

Dylan responded to writer's block and a couple of poorly received albums by beginning the Never Ending Tour. A show in Concord, California, on June 7, 1988, is now considered the first. Over more than two decades since, Dylan has averaged about 100 performances a year, playing more than 450 different songs. “A lot of people don’t like the road, but it’s as natural to me as breathing,” he said in 1997. “It’s the only place you can be who you want to be. I don’t want to put on the mask of celebrity. I’d rather just do my work and see it as a trade.”

10. Not Dark Yet

Just when it seemed like Dylan’s creative fire had waned—he hadn’t released an album of new material in six years—he produced 1997’s Time Out of Mind, his second collaboration with producer Daniel Lanois. The album, a riveting, unflinching look at lost love and mortality, drew comparisons to “Blood on the Tracks” and earned him three Grammy Awards, including album of the year. His music, Dylan said at the time, endures because it is built on the foundation of folk music of Muddy Waters, Charley Patton, Bill Monroe, Hank Williams and Woody Guthrie. “I really was never any more than what I was—a folk musician who gazed into the grey mist with tear-blinded eyes and made up songs that floated in a luminous haze,” he wrote in Chronicles, the first volume of his memoir. “I wasn’t a preacher performing miracles.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)