The Transformation of Freshkills Park From Landfill to Landscape

Freshkills was once the biggest landfill in the world. Today, it’s the biggest park in New York City

![]()

Looking toward Manhattan from Freshkills Park on Staten Island (image: Jimmy Stamp)

It’s like an old saying goes: One man’s trash is another man’s 2,200 acre park.

In 2001, Freshkills was the biggest dump in the world. Hundreds of seagulls circled the detritus of 8 million lives. Slowly decomposing piles of garbage were pushed around by slow-moving bulldozers to make room for more of the same. More than times the size of Central Park, the Staten Island landfill was established in 1948 by Robert Moses, the self-proclaimed “master builder” of New York City, responsible for much of the city’s controversial infrastructure and urban development policies during the mid-20th century. The landfill, which was only one in a series of New York landfills opened by Moses, was intended to be a temporary solution to New York’s growing need for waste disposal. The dumping would also serve the secondary purpose of preparing the soft marshland for construction – Moses envisioned a massive residential development on the site. That didn’t happen. Instead, Freshkills became the city’s only landfill and, at it’s peak in 1986, the once fertile landscape was receiving more than 29,000 tons of trash per day.

Early photo of Freshkills landfill (image: Chester Higgins via wikimedia commons)

Fast forward to 2012. Freshkills is the biggest park in New York City. Dozens of birds circle the waving grasses, spreading seeds across the hillside. Slowly drifting kites hang in the air above mothers pushing strollers along dirt paths and kayakers paddling through blue waters. It is an amazing synthesis of natural and engineered beauty. During my recent tour of the former landfill it was impossible to imagine that I was walking over 150 million tons of solid waste.

The nearly miraculous transformation is due largely to the efforts of New York City Department of Sanitation and the Department of Parks and Recreation, as well as many other individuals and organizations. It is an absolutely massive feat of design and engineering that is still 30 years from completion. To guide this development, the DPR have a master plan from a multidisciplinary team of experts led by landscape architect James Corner of Field Operations, who was selected to take on the development during an international design competition organized by the City of New York in 2001.

Corner, perhaps best known for his work on the Manhattan High Line, is also responsible for Phase One of Freshkills’s development, which focuses on making the park accessible to the public and installing smaller community parks for the neighborhoods adjacent to Freshkills. Schmul Park, a playground that will serve as a gateway to the North Park, recently celebrated its ribbon cutting, and new sports fields should be opened before the end of the year.

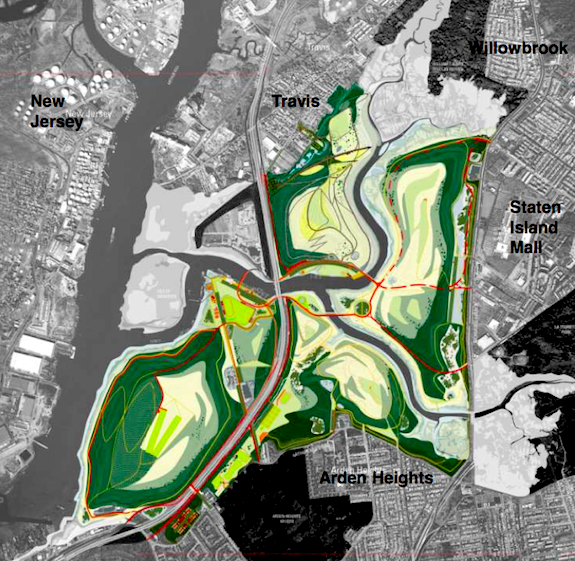

The current Freshkills master plan, prepared by landscape architecture firm Field Operations (image: New York Department of Parks and Recreation)

Corner’s plan identifies five main areas in Freshkills, each with distinct offerings, designed and programmed to maximize specific site opportunities and constraints. Planned features include nature preserves, animal habitats, a seed plot, walking and bike paths, picnic areas, comfort stations, event staging areas, and every other amenity you could possibly ask for in a public park. While James Corner may have planned the park, the landscape itself is being “designed” by the birds, squirrels, bees, trees, and breezes that have returned to populate the new landscape since 2001. These volunteers, including 84 species of birds, are helping to hasten the restoration of the wetlands landscape by dropping and planting seeds, pollinating flowers, and just generally doing what comes naturally. A 2007 survey also identified muskrats, rabbits, cats, mice, raccoons and even white-tailed deer, which are believed to have migrated from New Jersey.

Freshkills today (image: Jimmy Stamp)

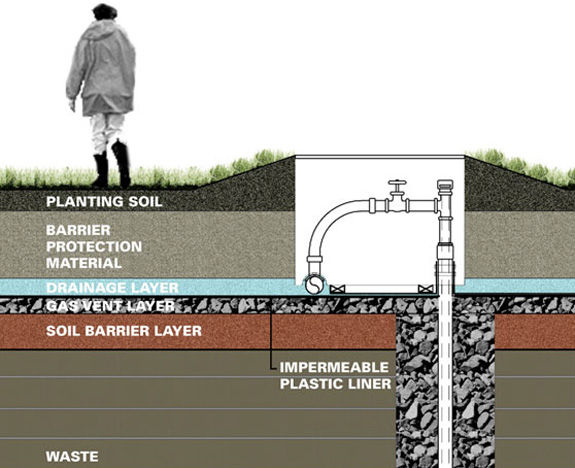

But how did the Freshkills landfill become Freshkills landscape? How do you safely cover a garbage dump? My first thought was that they would just pore concrete over the entire thing and call it day. I apparently know nothing about landfills. And probably not that much about concrete. The reality is a lot more complex. An elaborate and somewhat experimental six-layer capping system covers the entire landfill. But if you’re like me –and again, I know nothing about landfills– you may be wondering if the mounds of trash will shrink as they decompose until the entire hillside becomes a grassy plain (or, as I speculated, subterranean concrete caverns).

The answer is no. In fact, the garbage has already compressed as much as it ever will and any future change will be nominal. But to ensure this stability, before the capping was done, the trash heaps were covered with compressed soil and graded into the terraced hills seen today. While the resulting beautiful rolling hills offer incredible views all the way to Manhattan, it’s also kind of disgusting to think 29,000 tons of garbage that will just be there forever. Good job humans. But I digress. The complex multi-phase capping process is perhaps best described with a simple image.

diagram of Freshkills landfill capping (image: New York Department of Parks and Recreation)

You may be wondering about the plumbing in the above image. The landfill may be stabilized, but it still produces two primary byproducts: methane gas and leachate, a fetid tea brewed by rainwater and garbage. During the renewal of Freshkills, the excess of methane gas has been put to good use by the Department of Sanitation, who harvest the gas from the site to sell to National Grid energy company, earning the city $12 million in annual revenue. The only sign that this site was a former landfill are the methane pumps that periodically emerge from the surface of the ground like some mysterious technological folly. The leachate, however, is more of a problem. Although Moses did have the foresight to locate the landfill in an area with a clay soil that largely prevents any seepage into nearby bodies of water, there is always the risk that some leachate will escape. The new park addresses this risk with the landfill caps, which greatly reduces the amount of leachate produced, but also with pipes and water treatments facilities installed to purify any runoff until it is cleaner than the nearby Arthur Kill. To ensure their system works, 238 groundwater monitoring wells were installed to track water quality.

As the DPR continues the development of Freshkills, they’re dedicated to using state-of-the-art land reclamation techniques, safety monitoring equipment, and alternative energy resources to ensure that the new landscape is safe and sustainable.

Methane pump, man in hat and Manhattan (image: Jimmy Stamp)

Today, Freshkills may look like a wild grassland, but not all the piles of garbage are capped yet, although its almost impossible to tell. Take, for instance, the green hill at the center of the following photograph:

The green hill at the center of the photograph conceals the rubble of the World Trade Center (image: Jimmy Stamp)

You’re looking at what remains of the rubble transported off Manhattan in the wake of 9/11. Freshkills was reopened after the attacks to help expedite the cleanup and recovery. Today, the rubble just looks like part of the park. The only step that has been taken is to cover the area with clean soil. All the grasses and bushes are natural. It’s amazing and a little unsettlling. When you see the site in person, and you know what you’re looking at, it’s still hard to comprehend what you’re seeing. It’s a strange and visceral experience to see this green hill and then to turn your head and see the Manhattan skyline and the glint of the clearly visible One World Trade Center. It’s hard to reconcile the feelings that so such beauty can come from so much destruction. Currently, there are plans for an earthwork memorial to be installed on the site.

A rendering of the planned bird observation tower for the Freshkills North Park (image: New York Department of Parks and Recreation)

In 2042, Freshkills will be the most expansive park in New York. A symbol of renewal for the entire city. Slowly rotating wind turbines and photovoltaic panels will power the park’s comprehensive network of amenities. The biome, baseball fields, and bike paths concealing the refuse of another generation. A symbol of wasteful excess will have become a symbol of renewal.

If you’re interested in visiting Freshkills, the next public tour takes place on November 3.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)