The Trouble With Autobiography

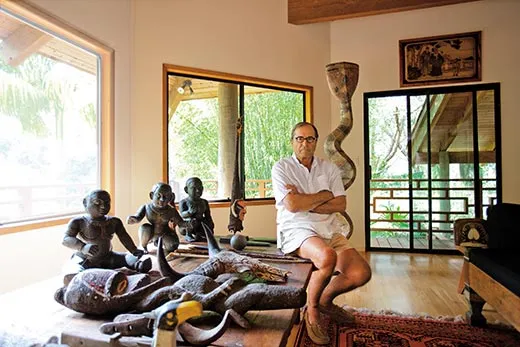

Novelist and travel writer Paul Theroux examines other authors’ autobiographies to prove why this piece will suffice for his

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Theroux-at-home-in-Hawaii-631.jpg)

I was born, the third of seven children, in Medford, Massachusetts, so near to Boston that even as a small boy kicking along side streets to the Washington School, I could see the pencil stub of the Custom House Tower from the banks of the Mystic River. The river meant everything to me: it flowed through our town, and in reed-fringed oxbows and muddy marshes that no longer exist, to Boston Harbor and the dark Atlantic. It was the reason for Medford rum and Medford shipbuilding; in the Triangular Trade the river linked Medford to Africa and the Caribbean—Medford circulating mystically in the world.

My father noted in his diary, “Anne had another boy at 7:25.” My father was a shipping clerk in a Boston leather firm, my mother a college-trained teacher, though it would be 20 years before she returned to teaching. The Theroux ancestors had lived in rural Quebec from about 1690, ten generations, the eleventh having migrated to Stoneham, up the road from Medford, where my father was born. My father’s mother, Eva Brousseau, was part-Menominee, a woodland people who had been settled in what is now Wisconsin for thousands of years. Many French soldiers in the New World took Menominee women as their wives or lovers.

My maternal grandparents, Alessandro and Angelina Dittami, were relative newcomers to America, having emigrated separately from Italy around 1900. An Italian might recognize Dittami (“Tell me”) as an orphan’s name. Though he abominated any mention of it, my grandfather was a foundling in Ferrara. As a young man, he got to know who his parents were—a well-known senator and his housemaid. After a turbulent upbringing in foster homes, and an operatic incident (he threatened to kill the senator), Alessandro fled to America and met and married my grandmother in New York City. They moved to Medford with the immigrant urgency and competitiveness to make a life at any cost. They succeeded, becoming prosperous, and piety mingled with smugness made the whole family insufferably sententious.

My father’s family, country folk, had no memory of any other ancestral place but America, seeing Quebec and the United States as equally American, indistinguishable, the border a mere conceit. They had no feeling for France, though most of them spoke French easily in the Quebec way. “Do it comme ils faut,” was my father’s frequent demand. “Mon petit bonhomme!” was his expression of praise, with the Quebecois pronunciation “petsee,” for petit. A frequent Quebecois exclamation “Plaqueteur!,” meaning “fusser,” is such an antique word it is not found in most French dictionaries, but I heard it regularly. Heroic in the war (even my father’s sisters served in the U.S. military), at home the family was easygoing, and self-sufficient, taking pleasure in hunting and vegetable gardening and raising chickens. They had no use for books.

I knew all four of my grandparents and my ten uncles and aunts pretty well. I much preferred the company of my father’s kindly, laconic, unpretentious and uneducated family, who called me Paulie.

And these 500-odd words are all I will ever write of my autobiography.

At a decisive point—about the age I am now, which is 69—the writer asks, “Do I write my life, or leave it to others to deal with?” I have no intention of writing an autobiography, and as for allowing others to practice what Kipling called “the Higher Cannibalism” on me, I plan to frustrate them by putting obstacles in their way. (Henry James called biographers “post mortem exploiters.”)

Kipling summed up my feelings in a terse poem:

And for the little, little span

The dead are borne in mind,

Seek not to question other than

The books I leave behind.

But laying false trails, Kipling also wrote a memoir, Something of Myself, posthumously published, and so oblique and economical with the truth as to be misleading. In its tactical offhandedness and calculated distortion it greatly resembles many other writers’ autobiographies. Ultimately, biographies of Kipling appeared, questioning the books he left behind, anatomizing his somewhat sequestered life and speculating (in some cases wildly) about his personality and predilections.

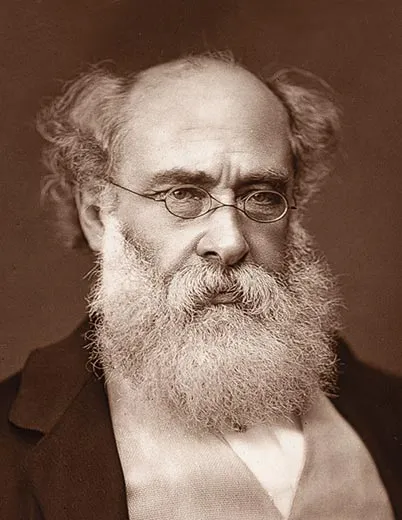

Dickens began his autobiography in 1847, when he was only 35, but abandoned it and, overcome with memories of his deprivations, a few years later was inspired to write the autobiographical David Copperfield, fictionalizing his early miseries and, among other transformations, modeling Mr. Micawber on his father. His contemporary, Anthony Trollope, wrote an account of his life when he was about 60; published a year after his death in 1882, it sank his reputation.

Straightforward in talking about his method in fiction, Trollope wrote, “There are those who...think that the man who works with his imagination should allow himself to wait till—inspiration moves him. When I have heard such doctrine preached, I have hardly been able to repress my scorn. To me it would not be more absurd if the shoemaker were to wait for inspiration, or the tallow-chandler for the divine moment of melting. If the man whose business it is to write has eaten too many good things, or has drunk too much, or smoked too many cigars—as men who write sometimes will do—then his condition may be unfavourable for work; but so will be the condition of a shoemaker who has been similarly imprudent....I was once told that the surest aid to the writing of a book was a piece of cobbler’s wax on my chair. I certainly believe in the cobbler’s wax much more than the inspiration.”

This bluff paragraph anticipated the modern painter Chuck Close’s saying, “Inspiration is for amateurs. I just get to work.” But this bum-on-seat assertion was held against Trollope and seemed to cast his work in so pedestrian a way that he went into eclipse for many years. If writing his novels was like cobbling—the reasoning went—his books could be no better than shoes. But Trollope was being his crusty self, and his defiant book represents a particular sort of no-nonsense English memoir.

All such self-portraiture dates from ancient times, of course. One of the greatest examples of autobiography is Benvenuto Cellini’s Life, a Renaissance masterpiece, full of quarrels, passions, disasters, friendships and self-praise of the artist. (Cellini also says that a person should be over 40 before writing such a book. He was 58.) Montaigne’s Essays are discreetly autobiographical, revealing an immense amount about the man and his time: his food, his clothes, his habits, his travel; and Rousseau’s Confessions is a model of headlong candor. But English writers shaped and perfected the self-told life, by contriving to make it an art form, an extension of the life’s work, and even coined the word—the scholar William Taylor first used “autobiography” in 1797.

Given that the tradition of autobiography is rich and varied in English literature, how to account for the scarcity or insufficiency of autobiographies among the important American writers? Even Mark Twain’s two-volume expurgated excursion is long, strange, rambling and in places explosive and improvisational. Most of it was dictated, determined (as he tells us) by his mood on any particular day. Henry James’ A Small Boy and Others and Notes of a Son and Brother tell us very little of the man and, couched in his late and most elliptical style, are among his least readable works. Thoreau’s journals are obsessive, but so studied and polished (he constantly rewrote them), they are offered by Thoreau in his unappealing role of Village Explainer, written for publication.

E. B. White idealized Thoreau and left New York City aspiring to live a Thoreauvian life in Maine. As a letter writer, White, too, seems to have had his eye on a wider public than the recipient, even when he was doing something as ingenuous as replying to a grade school class about Charlotte’s Web.

Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, which is glittering miniaturism but largely self-serving portraiture, was posthumous, as were Edmund Wilson’s voluminous diaries. James Thurber’s My Life and Hard Times is simply jokey. S. J. Perelman came up with a superb title for his autobiography, The Hindsight Saga, but only got around to writing four chapters. No autobiographies from William Faulkner, James Baldwin, John Steinbeck, Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer or James Jones, to name some obvious American masters. You get the impression that such a venture might be regarded as beneath them or perhaps would have diminished the aura of shamanism. Some of these men encouraged tame biographers and found any number of Boswells-on-Guggenheims to do the job. Faulkner’s principal biographer neglected to mention an important love affair that Faulkner conducted, yet found space to name members of a Little League team the writer knew.

The examples of American effort at exhaustive autobiography—as opposed to the selective memoir—tend to be rare and unrevealing, though Kay Boyle, Eudora Welty and Mary McCarthy all wrote exceptional memoirs. Gore Vidal has written an account of his own life in Palimpsest, and John Updike had an early stab at his in Self-Consciousness; both men were distinguished essayists, which the non-autobiographers Faulkner, Hemingway, Steinbeck and some of the others never were—perhaps a crucial distinction. Lillian Hellman and Arthur Miller, both playwrights, wrote lengthy autobiographies, but Hellman in her self-pitying Pentimento, neglects to say that her longtime lover, Dashiell Hammett, was married to someone else, and in Timebends Miller reduces his first wife, Mary Slattery, to a wraithlike figure who flickers through the early pages of his life.

“Everyone realizes that one can believe little of what people say about each other,” Rebecca West once wrote. “But it is not so widely realized that even less can one trust what people say about themselves.”

English autobiography generally follows a tradition of dignified reticence that perhaps reflects the restrained manner in which the English distance themselves in their fiction. The American tendency, especially in the 20th century, was to intrude on the life, at times blurring the line between autobiography and fiction. (Saul Bellow anatomized his five marriages in his novels.) A notable English exception, D. H. Lawrence, poured his life into his novels—a way of writing that recommended him to an American audience. The work of Henry Miller, himself a great champion of Lawrence, is a long shelf of boisterous reminiscences, which stimulated and liberated me when I was young—oh, for that rollicking sexual freedom in bohemian Paris, I thought, innocent of the fact that by then Miller was living as a henpecked husband in Los Angeles.

The forms of literary self-portraiture are so various I think it might help to sort out the many ways of framing a life. The earliest form may have been the spiritual confession—a religious passion to atone for a life and to find redemption; St. Augustine’s Confessions is a pretty good example. But confession eventually took secular forms—confession subverted as personal history. The appeal of Casanova’s The Story of My Life is as much its romantic conquests as its picaresque structure of narrow escapes. You would never know from Somerset Maugham’s The Summing Up, written in his mid-60s (he died at the age of 91), that, though briefly married, he was bisexual. He says at the outset, “This is not an autobiography nor is it a book of recollections,” yet it dabbles in both, in the guarded way that Maugham lived his life. “I have been attached, deeply attached, to a few people,” he writes, but goes no further. Later he confides, “I have no desire to lay bare my heart, and I put limits to the intimacy that I wish the reader to enter upon with me.” In this rambling account, we end up knowing almost nothing about the physical Maugham, though his sexual reticence is understandable, given that such an orientation was unlawful when his book was published.

The memoir is typically thinner, provisional, more selective than the confession, undemanding, even casual, and suggests that it is something less than the whole truth. Joseph Conrad’s A Personal Record falls into this category, relating the outward facts of his life, and some opinions and remembrances of friendships, but no intimacies. Conrad’s acolyte Ford Madox Ford wrote any number of memoirs, but even after reading all of them you have almost no idea of the vicissitudes (adulteries, scandals, bankruptcy) of Ford’s life, which were later recounted by a plodding biographer in The Saddest Story. Ford rarely came clean. He called his writing “impressionistic,” but it is apparent that the truth bored him, as it bores many writers of fiction.

Among the highly specialized, even inimitable, forms of small-scale autobiography I would place Jan Morris’ Conundrum, which is an account of her unsatisfactory life as a man, her profound feeling that her sympathies were feminine and that she was in essence a woman. The solution to her conundrum was surgery, in Casablanca in 1972, so that she could live the rest of her life as a woman. Her life partner remained Elizabeth, whom she had, as James Morris, married many years before. Other outstanding memoirs-with-a-theme are F. Scott Fitzgerald’s self-analysis in The Crack-Up, Jack London’s John Barleycorn, a history of his alcoholism, and William Styron’s Darkness Visible, an account of his depression. But since the emphasis in these books is pathological, they are singular for being case histories.

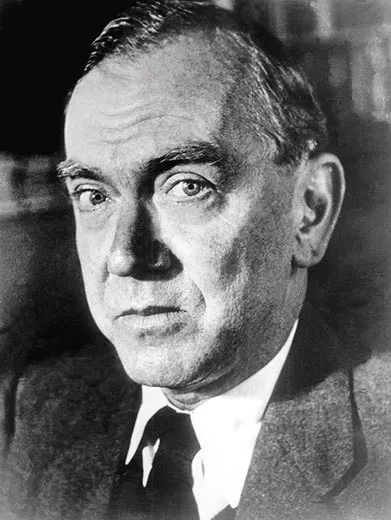

In contrast to the slight but powerful memoir is the multivolume autobiography. Osbert Sitwell required five volumes to relate his life, Leonard Woolf five as well, adding disarmingly in the first volume Sowing, his belief that “I feel profoundly in the depths of my being that in the last resort nothing matters.” The title of his last volume, The Journey Not the Arrival Matters, suggests that he might have changed his mind. Anthony Powell’s To Keep the Ball Rolling is the overall title of four volumes of autobiography—and he also published his extensive journals in three volumes. Doris Lessing, Graham Greene, V. S. Pritchett and Anthony Burgess have given us their lives in two volumes each.

This exemplary quartet is fascinating for what they disclose—Greene’s manic-depression in Ways of Escape, Pritchett’s lower middle-class upbringing in A Cab at the Door and his literary life in Midnight Oil, Burgess’ Manchester childhood in Little Wilson and Big God and Lessing’s disillusionment with communism in Walking in the Shade. Lessing is frank about her love affairs, but omitting their passions, the men in this group exclude the emotional experiences of their lives. I think of a line in Anthony Powell’s novel Books Do Furnish a Room, where the narrator, Nicholas Jenkins, reflecting on a slew of memoirs he is reviewing, writes, “Every individual’s story has its enthralling aspect, though the essential pivot was usually omitted or obscured by most autobiographers.”

The essential pivot for Greene was his succession of passionate liaisons. Though he did not live with her, he remained married to the same woman until his death. He continued to pursue other love affairs and enjoyed a number of long-term relationships, virtual marriages, with other women.

Anthony Burgess’ two volumes of autobiography are among the most detailed and fully realized—seemingly best-recalled—I have ever read. I knew Burgess somewhat and these books ring true. But it seems that much was made up or skewed. One entire biography by a very angry biographer (Roger Lewis) details the numerous falsifications in Burgess’ book.

V. S. Pritchett’s two superb volumes are models of the autobiographical form. They were highly acclaimed and best sellers. But they were also canny in their way. Deliberately selective, being prudent, Pritchett didn’t want to upset his rather fierce second wife by writing anything about his first wife, and so it is as if Wife No. 1 never existed. Nor did Pritchett write anything about his romancing other women, something his biographer took pains to analyze.

I never regarded Pritchett, whom I saw socially in London, as a womanizer, but in his mid-50s he revealed his passionate side in a frank letter to a close friend, saying, “Sexual puritanism is unknown to me; the only check upon my sexual adventures is my sense of responsibility, which I think has always been a nuisance to me...Of course I’m romantic. I like to be in love—the arts of love then become more ingenious and exciting...”

It is a remarkable statement, even pivotal, which would have given a needed physicality to his autobiography had he enlarged on this theme. At the time of his writing the letter, Pritchett was conducting an affair with an American woman. But there is no sentiment of this kind in either of his two volumes, where he presents himself as diligent and uxorious.

Some writers not only improve on an earlier biography but find oblique ways to praise themselves. Vladimir Nabokov wrote Conclusive Evidence when he was 52, then rewrote and expanded it 15 years later, as Speak, Memory, a more playful, pedantic and bejeweled version of the first autobiography. Or is it fiction? At least one chapter he had published in a collection of short stories (“Mademoiselle O”) years earlier. And there is a colorful character whom Nabokov mentions in both versions, one V. Sirin. “The author that interested me most was naturally Sirin,” Nabokov writes, and after gushing over the sublime magic of the man’s prose, adds: “Across the dark sky of exile, Sirin passed... like a meteor, and disappeared, leaving nothing much else behind him than a vague sense of uneasiness.”

Who was this Russian émigré, this brilliant literary paragon? It was Nabokov himself. “V. Sirin” was Nabokov’s pen name when, living in Paris and Berlin, he still wrote novels in Russian, and—ever the tease—he used his autobiography to extol his early self as a romantic enigma.

Like Nabokov, Robert Graves wrote his memoir, Good-Bye to All That, as a youngish man, and rewrote it almost 30 years later. Many English writers have polished off an autobiography while they were still relatively young. The extreme example is Henry Green who, believing he might be killed in the war, wrote Pack My Bag when he was 33. Evelyn Waugh embarked on his autobiography in his late 50s, though (as he died at the age of 62) managed to complete only the first volume, A Little Learning, describing his life up to the age of 21.

One day, in the Staff Club at the University of Singapore, the head of the English Department, my then boss, D. J. Enright, announced that he had started his autobiography. A distinguished poet and critic, he would live another 30-odd years. His book, Memoirs of a Mendicant Professor, appeared in his 49th year, as a sort of farewell to Singapore and to the teaching profession. He never revisited this narrative, nor wrote a further installment. The book baffled me; it was so discreet, so impersonal, such a tiptoeing account of a life I knew to be much richer. It was obvious to me that Enright was darker than the lovable Mr. Chips of this memoir; there was more to say. I was so keenly aware of what he had left out that ever after I became suspicious of all forms of autobiography.

“No one can tell the whole truth about himself,” Maugham wrote in The Summing Up. Georges Simenon tried to disprove this in his vast Intimate Memoirs, though Simenon’s own appearance in his novel, Maigret’s Memoirs—a young ambitious, intrusive, impatient novelist, seen through the eyes of the old shrewd detective—is a believable self-portrait. I’d like to think that a confession in the old style is attainable, but when I reflect on this enterprise, I think—as many of the autobiographers I’ve mentioned must have thought—how important keeping secrets is to a writer. Secrets are a source of strength and certainly a powerful and sustaining element in the imagination.

Kingsley Amis, who wrote a very funny but highly selective volume of memoirs, prefaced it by saying that he left out a great deal because he did not wish to hurt people he loved. This is a salutary reason to be reticent, though the whole truth of Amis was revealed to the world by his assiduous biographer in some 800 pages of close scrutiny, authorized by the novelist’s son: the work, the drinking, the womanizing, the sadness, the pain. I would have liked to read Amis’ own version.

It must occur as a grim foreboding to many writers that when the autobiography is written it is handed to a reviewer for examination, to be graded on readability as well as veracity and fundamental worth. This notion of my life being given a C-minus makes my skin crawl. I begin to understand the omissions in autobiography and the writers who don’t bother to write one.

Besides, I have at times bared my soul. What is more autobiographical than the sort of travel book, a dozen tomes, that I have been writing for the past 40 years? In every sense it goes with the territory. All you would ever want to know about Rebecca West is contained in the half-million words of Black Lamb and Gray Falcon, her book about Yugoslavia. But the travel book, like the autobiography, is the maddening and insufficient form that I have described here. And the setting down of personal detail can be a devastating emotional experience. In the one memoir-on-a-theme that I risked, Sir Vidia’s Shadow, I wrote some of the pages with tears streaming down my face.

The assumption that the autobiography signals the end of a writing career also makes me pause. Here it is, with a drum roll, the final volume before the writer is overshadowed by silence and death, a sort of farewell, as well as an unmistakable signal that one is “written out.” My mother is 99. Perhaps, if I am spared, as she has been, I might do it. But don’t bank on it.

And what is there to write? In the second volume of his autobiography, V. S. Pritchett speaks of how “the professional writer who spends his time becoming other people and places, real or imaginary, finds he has written his life away and has become almost nothing.” Pritchett goes on, “The true autobiography of this egotist is exposed in all its intimate foliage in his work.”

I am more inclined to adopt the Graham Greene expedient. He wrote a highly personal preface to each of his books, describing the circumstances of their composition, his mood, his travel; and then published these collected prefaces as Ways of Escape. It is a wonderful book, even if he did omit his relentless womanizing.

The more I reflect on my life, the greater the appeal of the autobiographical novel. The immediate family is typically the first subject an American writer contemplates. I never felt that my life was substantial enough to qualify for the anecdotal narrative that enriches autobiography. I had never thought of writing about the sort of big talkative family I grew up in, and very early on I developed the fiction writer’s useful habit of taking liberties. I think I would find it impossible to write an autobiography without invoking the traits I seem to deplore in the ones I’ve described—exaggeration, embroidery, reticence, invention, heroics, mythomania, compulsive revisionism, and all the rest that are so valuable to fiction. Therefore, I suppose my Copperfield beckons.

Paul Theroux’s soon to be published The Tao of Travel is a travel anthology.