The World’s Great Structures Built With Legos

For 15 years, Adam Reed Tucker was an architect. Now, he constructs models of famous buildings with thousands of Legos

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lego-buildings-631.jpg)

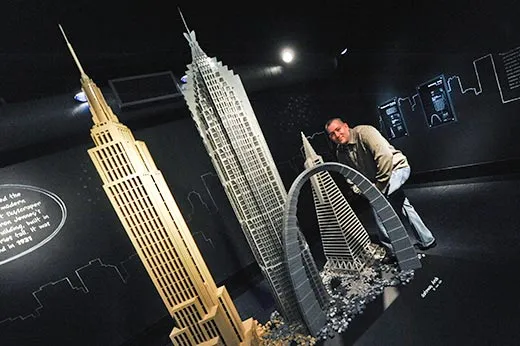

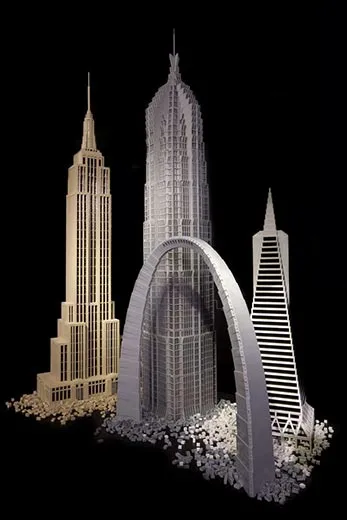

Former Chicago-based professional architect Adam Reed Tucker is one of 11 Lego-certified professionals in the world, designing scale models of famous buildings and structures out of Lego bricks. His models, including the World Trade Center, the Gateway Arch, Fallingwater and others, are on display in the National Building Museum until September 5, 2011, in the exhibit, “LEGO Architecture: Towering Ambition” in Washington, D.C.

You got your degree in architecture from Kansas State University in 1996. How did you get from there to Lego Certified Professional?

In a nutshell, I worked for a number of architecture firms, and then I had my own practice. One day I had this idea of doing something a little different, being inspired by the events of 9/11 and realizing that a lot of people from the general public were intimidated by vertical architecture—skyscrapers. They weren’t really visiting the Empire State Building, the Sears Tower, because of what happened to the World Trade Center.

So, I thought it would be kind of neat to educate people on the engineering and the design that goes into these buildings. And I really didn’t know how to go about it.

I thought “Well, the brick as a medium could be kind of whimsical to offset the intimidating nature of architecture.” It’s something that’s not typically thought of outside of its usefulness as a toy.

I went out one day and I went to Toys R’ Us and I filled up several shopping carts with Lego sets to get reacquainted with the brick. I didn’t know what elements, didn’t know what colors Lego had been making since I had stopped playing with them probably back in 1981. I just needed to get familiar with them to find out if they would work with my idea.

From there I started these large buildings and I was invited to a Lego event on the East Coast in 2006. I brought some of my buildings there—the initial ideas behind Lego Architecture. I actually got to meet some Lego executives and I shared some of my vision and my passion for what I was attempting to do with their product, and essentially they invited me with open arms into a relationship with the Lego group as someone who is using the brick in a positive and entrepreneurial way.

As a child did you have the same passion of making your own creations.?

Oh definitely, I probably got my first box [of Legos] when I was 3 years old, 4 years old. Probably stopped playing with them when I was 13. So, for about 10 years of my childhood, probably not much different than other young boys around that time. It was Star Wars action figures and it was Legos.

Do you think that passion for more building-oriented toys led you to becoming an architect?

Definitely, there is a component there. I actually started in art, in graphic design, and found it to be not really challenging enough. So, when you start adding the fields of science with art, you get architecture and you start dealing with natural forces, physics, budgets, building codes, it helps to harness your creativity and provides, obviously, much more of a challenge with your art. So, it has to be functional art instead of arbitrary art.

Tell me about your design process.

I have reference photographs, and what I do is—I don’t use any computers, I don’t do any sketching—I just do all free build in my mind based off of the interpretation that I naturally go through when I’m looking at a photograph or a reference image (and) my knowledge of all the different elements that Lego makes. That combination allows me to create and capture the essence of a structure into its pure structural form.

Essentially what I’m doing is not necessarily getting caught up in the details of the design, but I’m trying to naturally provide a balance between allowing the model to still look as if its made out Lego, then also trying to balance and capture the structure to where it is obviously identifiable, but doing so in, you know, kind of an artistic capture.

The process is a lot of designing in my head and then taking apart and then building again and then modifying, tweaking, adjusting. I’ll probably build and rebuild a section of a particular model—whether it is a large building or a small set that I’m working on for LegoArchitecture 5 to 15 times just to get it right. So, there’s no answer, there’s no instruction, it’s something that you’re just doing as the model is evolving as you start looking at it and as it starts going together, using different Lego elements. There’s obviously more than one way to design a building.

So, given all those challenges, which was the most frustrating to create?

I pick a model based on many criteria. But probably the biggest criteria is something I’m personally interested in, thinking, therefore, that maybe other people would be interested in it as well.

So while there’s many buildings out there, there’s many things you could do, that doesn’t mean you should do them. For instance, with the St. Louis Arch, I was trying to replicate a structure that does three geometric complexities all at the same time. Those would be a triangular section, a telescoping or tapering as it goes up—meaning the keystone is exactly one third the size of the base of each leg—and obviously the last and most difficult and tricky component is the catenary curve, which by definition means every single degree of change is different and unique, so it’s not an equilateral arch or a typical arch. Those three factors are interesting and challenging enough, and then trying to replicate it with square bricks, well that’s the challenge there.

No one had really done that before and so, for me, the challenge was: how can that be done? That was probably, even though it was one of my smaller models, it was one of the trickier ones.

You mentioned that you have lots of buildings on your horizon. Which would be at the top of that list?

Well, currently, I’m working on the Miglan-Beitler building, which most people are not familiar with because it was never built. It was proposed, I believe, back in 1987. It was supposed to be a 125-story Art Deco skyscraper in Chicago. I find it to be a very beautiful building, and I think that’s one component I haven’t touched on yet with you. And that is the ability of doing things that were never realized. For instance, most people in the world will get to see what the Chicago Spire looks like, or 7 South Dearborn or the Miglan-Beitler building or maybe ten years from now, no one will get to see or remember what the World Trade Center looked like. And, so, with that I’m able to capture these buildings that no longer exist or never will exist and I think that’s a really neat component that I can share with people.

The one question I do get a lot of is, ”why don’t you do one of your own designs instead of replicating other architects’ designs and other firms, have you ever thought of doing your own?” So, at some point, I think that that might be kind of neat to explore, doing an original design. So, maybe that will be one of my next projects too.

What might inspire you, in terms of that original design?

But what would inspire me would probably be the style that I have, which is very close to the style of Santiago Calatrava, with the proportioning and the vocabulary and characteristics of, say, Frank Lloyd Wright.

One of the great things about doing this is that it gives me the freedom to do things but not live in a world of reality in a sense. It’s kind of like I am my own architect, my own client, my own contractor, my own crane operator, as funny as that sounds. But, really I get to be in control of all these different processes.

Are there any unLegoable buildings?

I would say “no” based on the scale. That’s the tricky component. Anything can be done out of Legos. It’s just a matter of scale. So, for instance, could you replicate Wrigley Field in the palm of your hand? Probably not. But, could you replicate Wrigley Field given a 5-foot by 5-foot base from which to work? Probably.