The World’s Largest Collection of Coffee Cup Lids

With over 500 different disposable plastic lids, the architect-collector has pieced together a history of American innovation and culture

![]()

Under Louise Harpman’s bed, in acid-free boxes, there are superior double-walled, climate-controlled and UV-protected cases filled to the brim with plastic coffee cup lids. Over 550 to be exact—and the number is growing.

“When I’m in a 7-Eleven and I see a lid I’ve never seen before I think ‘Oh wow! This is fantastic!’ So I grab a couple thinking there is somebody out there who is going to want to trade with me,” Harpman says. “Most of the time, I am surprised if there are three other people in the world that are interested in this stuff.”

Harpman knows at least one other: Her business partner Scott Specht. Together they run an architecture firm in New York City and are the proud owners of the largest collection of independently patented drink-through plastic cup lids in America. The collection got some attention in 2005 with its inclusion in Proteus Gowanus, a Brooklyn gallery, and a feature in Cabinet to follow, and next week, over 50 of their lids will appear in the National Museum of American History’s new exhibit, “FOOD: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000.”

An architecture and design professor at New York University, Harpman has taught classes on collecting and museum culture. She argues that the humble lids represent a major shift in American “to-go” culture, and how most of us overlook the ordinary.

“There are collectors who are completists who want to make sure they have one or two of everything that’s out there,” she says. “I’m not that kind of collector; there’s no questing for these lids for me. I won’t consciously go into every place that sells coffee just to see what lids they are using. I have a story that goes with it, and the story is pretty important to me, too.”

Their stockpile of flimsy, mostly-white covers began in 1982 when Harpman and Specht were in school, and noticed a trick other college students on the Yale School of Architecture’s campus would use when rushing to class, coffee in hand.

“Everyone would have their little ways of peeling back part of the coffee lid so they could take it on the run,” she says. “By removing a small triangle from the top of the lid and discarding it, they could drink through the top, but it wouldn’t work very well.”

This method of detaching a piece from the lid, called the “guitar pick” by author and historian Philip Patton, got Harpman thinking: Where did this start? Who had these ideas first? What direction did the coffee lid take and where is it headed?

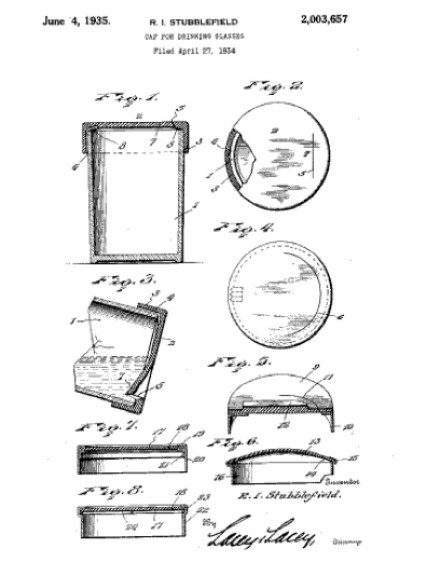

Architect, Louise Harpman, calls this patent submitted in 1934, the “Elusive Stubblefield Lid”—the earliest version she’s encountered of the plastic coffee cup lid we see today. Image courtesy of Google Patents.

The evolution of the plastic coffee cup lid is nonlinear and difficult to trace. There are multiple designers working independently for companies nationwide and a complex patent process that leaves plenty of room for ideas to get lost in the shuffle. Many patents are given and never go into production. Dig through the US patent registry and you’ll find one of the earliest drink-through lids submitted in 1934—What Harpman calls the “elusive” Stubblefield lid, or “Cap for Drinking Glasses.” She hesitates to call the lid a definitive “first” of its kind, as liquid containers that predate this design vary in function and form. Its main purpose was to help children drink beverages without spilling—useful for moms, certainly, but a long way from the lids we use for our morning latte today.

Food historian Cory Bernat, who reached out to Harpman about acquiring the lids for National Museum of American History, has researched “to go” culture extensively for the upcoming FOOD exhibit. She keeps stacks of Popular Mechanics on her desk dating back to the early 1940s. Her bookshelf is bursting with tattered cookbooks and catalogues. Harpman’s collection, Bernat says, is all about the context.

Cory Bernat prepares the coffee lids for installation in the new American History museum exhibit. Photo by Steve Velasquez

“What’s important about the coffee lid is the disposability feature—that people can think, ‘When I’m done with this I can stop holding it and not feel guilty.’ It’s uniquely a part of the second half of 20th-century America. You won’t travel to a foreign country and find people sipping coffee while walking.”

Bernat says the language used in the accompanying patent applications is integral in mapping out the evolution of “to go” culture. Each miniscule improvement in lid-design signals an innovative shift. Descriptors like “heat retention,” “mouth comfort,” “splash reduction” and “one-handed activation,” for example.

“These terms are all really thought out,” she says, “It sounds like they are engineering automobiles or something.”

Harpman contends that the blueprint for a coffee lid actually is just as technical as a car’s. She’s created taxonomy for the collection, which she details in Cabinet, that puts the lids into four categories: “Peel”, “Pucker”, “Pinch” and “Puncture.” With this method, she says she can almost trace the evolution backwards as some of the flaws in lid design emerge. The verbiage of the patents slowly uncovers answers to questions designers and consumers are asking: How can the lid stay on the cup so it doesn’t splash out? Once you punch through the lid, how can you ensure that it still has structural integrity? In other words, how can the design of the lid meet the increasing demand to drink coffee on the fly?

In the 1970s there were roughly nine individual patents for drink lids. By the ’80s, the number spiked to 26. But there are a few other examples of on-the-go lids that pre-date the ’80s lid boom, like the “Lip Openable Closure Cap for Liquid Containers” filed in 1966. But even this contraption is meant more for a thermos and other containers of the “non-spillable type.” The design points out flaws from previous lids on the market that don’t allow the user’s lips to form a proper seal over the opening that “generally prevents drinkers from avoiding spillage of the liquid.” It’s difficult to trace whether this particular lid ever made it into production, but the basic design elements, Harpman says, appear to be the “dormant genetic precursor” for newer lids like the Solo Traveler Plus that uses a second small piece of plastic to create a rotating cover over the mouth piece.

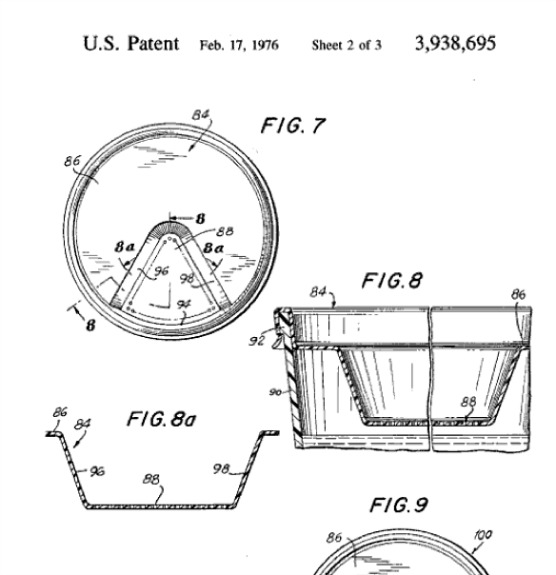

By the ’70s the language of the patents focuses on “carry out” beverages for use on “common carriers”—like planes and trains—that are subject to sudden movement. The “Drink-through slosh-inhibiting closure lids for potable open-top containers” filed by inventor Stanley Ruff in 1976, for example, promised to reduce the “slosh waves” upon “irregular or sudden movement of the container.” But like the “guitar pick” method she saw in college, these lids were also one-time use only and they don’t keep the coffee in the cup while the consumer is in motion.

This lid design from 1976 promised to reduce the “slosh waves” upon “irregular or sudden movement of the container.” Image courtesy of Google Patents.

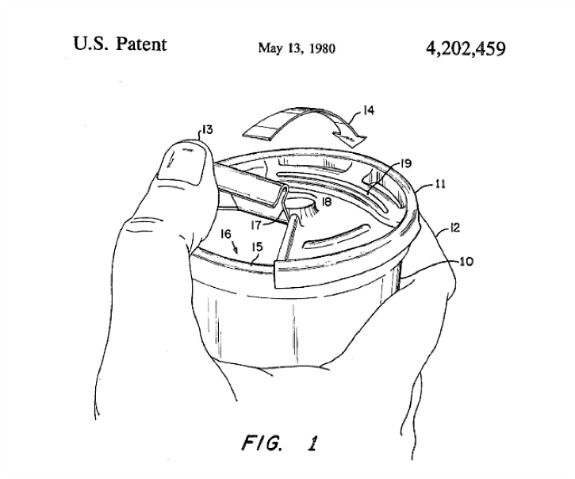

Up until the ’80s, lids were built so that along a perforated line, the drinker could punch through the lid to create an opening for consumption with no means of closing it back up. Harpman attributes the “peel back and click” (in the “Peel” category) design of lids like the “Disposable Cup Cover” filed in 1980 as the true beginning of the reusable lid.

“That moment where we decide we have to cover it back up again, then you start to come forward in the next ten years. You could have your first sip in the shop, close it back up and then take it with you and it’s still hot,” she says. “The idea wasn’t so much that the lid could close but that the design represented the need for immediate gratification—you just paid for this cup of coffee, you’ve got to wake up now.”

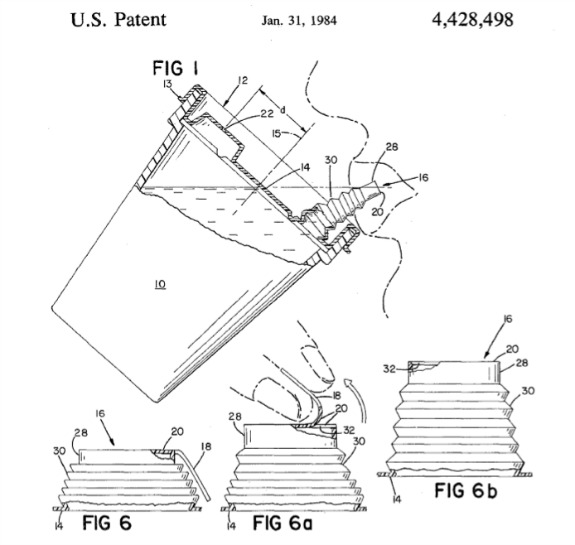

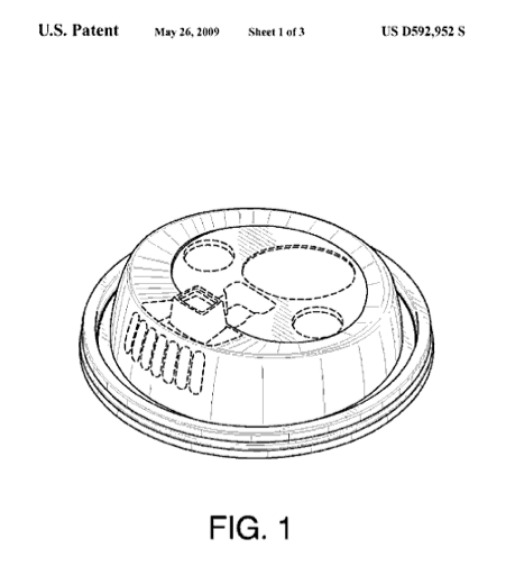

Cue the travel coffee cup boom with lids like the “Coffee Cup Travel Lid” filed in 1984, with it’s “sipping port” that allows the user to drink in motion without compromising the structure of the lid. In 1986, the Solo Traveler hit the scene and remains one of the most widely used coffee lids in America, even earning a spot in the Museum of Modern Art’s 2004 exhibition “Humble Masterpieces.”

The “Coffee Cup Travel Lid” filed in 1984, complete with “sipping port.” Image courtesy of Google Patents.

“I think most of the radical innovations occurred in the last 10 to 12 years alone,” she says. “More and more lids are coming out to cater to something that we have accepted as a need, right? That Americans need to take hot beverages to go.”

With the exception of a few improvements in user comfort that allowed room for the drinker’s nose and the invention of the dome lid that left space for fancy, foamy, lattes to fit under the cap without getting smushed, the coffee cup lid hasn’t changed much. In fact, a lot of the same dribble-causing imperfect seals are still out there, ruining blouses daily.

But in this series of problem solving, Harpman sees a future for the on-the-go coffee drinker, and she’s got a few theories as to which direction the products are headed based on what’s hit the market.

- The “Aromatic Coffee Lid” from MINT releases an aroma like hazelnut or vanilla once the steam hits the lid. This dynamic scent-flavor combo is something we’ve seen from the Dutch recipe for the stroopwafle, which were first enjoyed in the Netherlands in 1784.

- The Double Team sliding lid promises “coffee in your cup, not on your shirt!” and is good for multiple uses.

- This color-changing lid alerts coffee drinkers that the contents are hot by changing from coffee brown to bright red in color when the temp rises. If the section of the lid over the lip of the cup is red, it indicates that the cap has not been applied properly.

- Peets Coffee came out with a plan that gave disposable French presses to each of their customers in 2010. LA Weekly called it an “‘after 3 minutes’ To-Go cup,” Harpman calls it a “pain in the butt.”

As the demands consumers are putting on the design of these lids are changing, Harpman is certain of one thing: The more “on the go” America becomes, the more manufacturers must adapt their designs.

“When you put something in a museum, you say, ‘Oh, I’ve got to put a value on this,’ but nobody knows how to value this collection I’ve got, and it’s not for sale,” she says. “There is another kind of value I’m talking about, which is understanding that you are seeing part of a culture that would otherwise go into the landfill.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)